With talk of fiscal commissions and falling credit ratings, the federal debt has become a front-and-center issue in Washington for the first time in over a decade. Even those who call loudest for debt reduction, however, can't agree on how much is too much.

The debate over acceptable levels of debt and deficit has engaged economists and philosophers for years, with giants like John Maynard Keynes arguing for aggressive deficit spending during downturns, and Milton Friedman cautioning against well-intentioned efforts to micromanage an economy. The argument is alive today as America’s debts pile up.

But paying down the government’s debt can also cripple the economy. Where, then, is the perfect intersection between the need for growth, investment and ongoing services and the need to balance the budget?

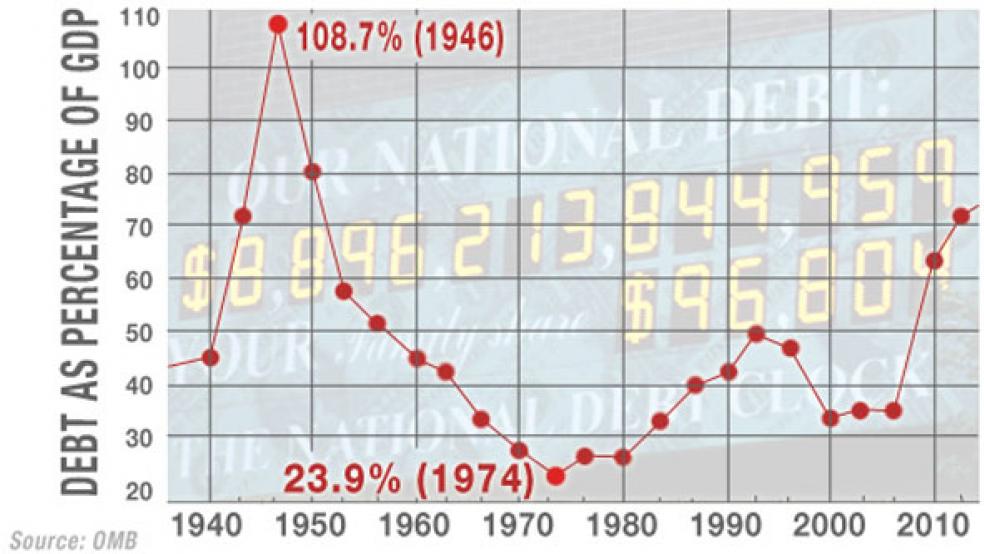

The number, according to experts, will emerge as some ratio of the nation’s debt to gross domestic product, a figure that crept above 50 percent in 2009 for the first time since World War II. Is that high enough to shake global confidence in the United States, or is it a comfortable number that helps lubricate the U.S. economic machine? The bottom lines resulting from the answers to these questions span trillions of dollars of potential spending, so the disagreements are anything but trivial.

"When the members of Congress start figuring out what these deficits mean for their favorite fun and games, this number is going to be a real fight," said Bill Frenzel, a former Republican House member who recently co-chaired a private commission on debt levels funded by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation (Full disclosure: Peter G. Peterson separately funds The Fiscal Times) and the Pew Charitable Trusts.

As a result of the Iraq war, tax cuts, bank rescues, two stimulus packages and a recession-driven slowdown in revenues, the annual budget deficit in 2009 — the difference between spending and revenues — skyrocketed to $1.4 trillion. That represents 9.9 percent of GDP, or about eight times the level before the economic downturn began in December 2007. As a general rule, economists assume that a deficit of 3 percent of GDP makes for a stable ratio because of nominal growth in the American economy.

As long as annual deficits remain at such high levels, the national debt — all accumulated deficits, plus interest — will continue to balloon. Debt sat at 40 percent of GDP in 2008, but in 2009 it reached 53 percent. Depending on assumptions about economic growth, this path could result in debt surpassing 70 percent of GDP by mid-decade and much higher after that, according to private and government estimates.

The experts’ assessments of the best possible debt level reflect assumptions about how patient U.S. creditors will be, how much borrowing squeezes economic growth, and above all what is politically feasible.

The Peterson-Pew commission and another independent panel, created by the National Research Council and the National Academy of Public Administration, have endorsed a ratio of 60 percent debt-to-GDP. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a prominent think tank, suggests 70 percent is more realistic. A recent paper by Carmen Reinhart, a professor at the University of Maryland, and Kenneth Rogoff, a scholar at Harvard, hints that even 90 percent or more would not harm growth in the United States. Every difference of 10 percent of GDP would be well over $1 trillion in federal spending.

Meanwhile, liberal groups emphasize the need to reduce the unemployment rate before worrying about debt.

The Obama administration predicts a debt-to-GDP ratio of 77 percent by the end of the decade, but White House Budget Director Peter Orszag dodged questions on Feb. 1 about whether that level is sustainable. If the administration can enact all of its proposed $1.2 trillion in savings — a big if — the deficit would drop to 4 percent of GDP by 2015, Orszag said.

The bipartisan fiscal commission that Obama announced Feb. 18 is charged with charting a sustainable course and finding further reductions, but Orszag declined to say what its mandate would be. "The commission hasn't even been yet named. Let's let it do its work and see what it can come up with," he said in response to a question about tax hikes. Obama has since suggested that everything, including broad tax increases, would be on the table.

The good news is that even massive debt burdens are manageable with the right policies. U.S. federal debt peaked at 108.7 percent of GDP in 1946, reflecting the cost of winning World War II. But brisk growth and postwar demobilization sent the ratio steadily downward for decades, until it bottomed out at 23.9 percent in 1974.

Some experts fret that U.S. debt levels will exhaust the good will of foreign creditors — not an issue in 1946 — but little consensus exists as to how much is too much.

"I have no idea what the number is," said Leonard Burman, a professor at Syracuse University who has studied debt crises. "Basket cases like Italy and Greece have massive debt levels and they have not gone south. And the United States is the biggest economy in history."

The uncertainty leaves some analysts convinced that the United States should simply watch the unemployment rate — now at 9.7 percent and expected to fall only slightly this year — before tackling debt reduction.

"It is just too context-dependent for the United States to say exactly what target we should have in mind," said Josh Bivens, an economist at the Economic Policy Institute.

Others have sifted through the data from the perspective of growth. The paper by Reinhart and Rogoff concluded that debt at 90 percent of GDP starts to reduce average economic growth rates by over 1 percent in industrialized countries.

"Very concretely, irrespective of how you slice the data sample, once you are past 90 percent, things go bad in terms of growth," Reinhart said. "But that is very different from saying this is the kind of debt level that the United States should shoot for."

The paper points out that debt levels are "importantly country specific," an implicit acknowledgement that the world’s only superpower has room, for now, to keep playing by its own rules.

James Horney, director of federal fiscal policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, which endorsed the 70 percent ratio, said that all the groups are seeking a number that is aggressive but realistic. "Our view is that you choose a target that will actually get action, otherwise you end up doing nothing because it was too ambitious."

Rudolph Penner, a member of both commissions endorsing a 60 percent debt-to-GDP ratio and former director of the Congressional Budget Office, emphasized that 60 percent "is not a magic number. It was clearly a matter of judgment."

Penner also conceded that the Peterson-Pew report calls for actions that Congress has rejected out of hand — like paying for its annual move to ease the burden of the Alternative Minimum Tax, expected to cost $233 billion over the next five years. But he also says that lawmakers have "no choice" but to deal with the deficit — sooner or later.

"That will happen as the result of a rational process or a crisis," he said.