As oil continues to gush into the Gulf of Mexico from BP’s sunken Deepwater Horizon rig, half a continent away a major new pipeline is delivering the first supplies of crude to refineries in Illinois. With the consistency of heavy molasses, the raw oil took about three months to travel some 1,073 miles.

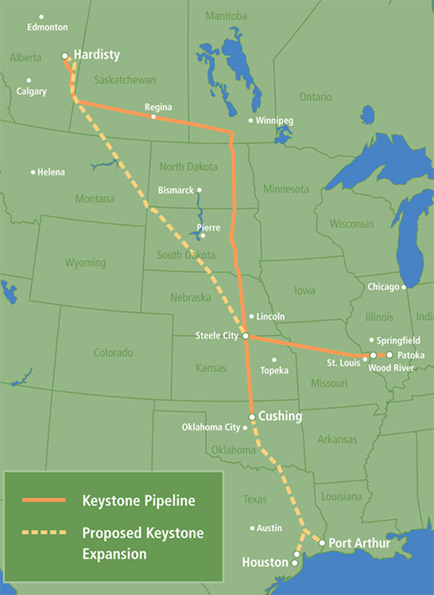

The pipeline is the first step in a $12 billion TransCanada Corp. project that aims to more than double the capacity of oil that can be piped into the U.S from Canada, just as Americans are looking for alternatives to offshore drilling and oil from the Middle East. Oil extracted from Alberta’s tar sands — deposits of dense, sticky sand, saturated with a viscous form of petroleum — account for about 20 percent of U.S. crude imports. The newly opened pipeline, known as Keystone I, is part of a network that, when completed, will wind 3,800 miles underground through three provinces and eight Great Plains states before terminating in Texas.

“Keystone will play an important role in linking a secure and growing supply of Canadian crude oil with the largest refining markets in the United States, significantly improving North American energy security,” Hal Kvisle, TransCanada’s president and CEO, said in a statement at the pipeline opening on June 30.

But it will come at a high price, both in dollars and risk to the environment. Canada’s tar sands are among the world’s most expensive source of new oil, about twice the cost of new Saudi production. The Gulf disaster has intensified scrutiny of all energy projects — and on the final stage of TransCanada’s pipeline project, in particular. With a second stage already under construction, extending the pipeline into Oklahoma, TransCanada is awaiting approval for a final link, Keystone XL, which would relay tar sands crude to Texas’ Gulf Coast.

Criticism of the final stage has focused on TransCanada’s request for a special waiver to build the 36-inch-in-diameter pipeline using thinner steel and to operate it at higher pressures than is standard in the U.S. In the wake of the Gulf disaster, where existing technologies were pushed beyond known limits, the request for special waivers “ought to pass higher technical scrutiny, and be more transparent, not less,” says Susan Casey-Lefkowitz, director of international programs at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Meanwhile, shifting market conditions mean the added capacity of TransCanada’s new network may not be needed for up to a decade. Plans for Keystone took shape in 2008, when oil prices were near a peak of $150 per barrel. Since then, global recession has sent prices back under $75 per barrel, shelving plans for new oil sands mining operations.

Yet refiners who signed on to get supplies from TransCanada’s project are still obliged to pay the company a fixed price even if, according to some estimates, the pipeline will be handling only half as much oil as originally planned. That suggests the Keystone’s additional capacity will drive oil prices higher, not lower.

Because the pipeline crosses an international border, the lead federal authorizing authority is the State Department, rather than agencies with more expertise in environmental risk assessment, such as the Environmental Protection Agency or the Transportation Department. “Of all the expertise relative to pipelines in the federal government I can’t imagine it would be at the State Department,” said Senator Mike Johanns, R-Neb., at a recent hearing on pipeline safety at the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science & Transportation.

Details of the pipeline’s draft environmental impact study (EIS) are coming under fire as well. A critically important estimate of the risk of pipeline failure suggests the pipeline would rupture only about once every 7,400 years, according to the State Department’s draft EIS. This was calculated by Houston-based Entrix, a technical consultant hired by the State Department and paid for by TransCanada, using proprietary formulas supplied by TransCanada.

“It’s too closed and cozy,” says Kate Colarulli, Dirty Fuels Campaign coordinator at the Sierra Club. “It’s like the Gulf Coast disaster waiting to happen all over again.” On June 23, 50 members of Congress sent Secretary of State Hillary Clinton a letter criticizing the draft impact study as incomplete. They said it doesn’t take into account the full impact of the environmental risks, nor does it weigh the White House’s stated priority to develop cleaner, lower carbon energy options first.

Criticism of the project comes on top of longstanding objections to the environmental impact of tar sands. Typically, ancient forests are razed to begin the mining process and expose the oil-rich sands. To release the oil, the sand is then heated, using enormous volumes of water and natural gas, and leaving behind enormous lakes of toxic waste. Extracting the oil uses three times more energy than conventional oil processes.

The oil is so heavy that it must be heated as it is piped to refineries, lest it congeal. Once at the refinery, oil from the sands requires more energy to distill and releases more air pollution in the process, says NRDC’s Casey-Lefkowitz.

With criticism of the project rising, TransCanada could face costly delays, pushing the project past its 2012 target to start oil flowing through the XL pipeline. And much of the petroleum it will deliver may not end up in U.S. tanks. Given higher prices for fuel in Europe, and soft demand in the U.S., a substantial share of the tar sands will likely be refined and sold as diesel to European drivers, according to an analysis by Greenpeace. Ceres, a coalition of investors and environmental groups, says new supplies may never come on line because of the high costs to open new capacity in Canada, as well as the likelihood that Low Carbon Fuel Standards, already enacted for federal purchasing and in California, will limit sales of tar sands crude.