Medicare last week finally leveled a pre-emptive strike against smoking and agreed to pay for counseling for senior smokers who are not yet sick. The new smoking cessation program for seniors might seem a tad late. People usually smoke for decades before they get cancer, emphysema, heart disease and other smoking-related disorders — just in time for Medicare to pick up the tab. But the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) decision memo noted that even older smokers who quit can see fairly quick payback in terms of reduced illness.

Smoking costs the U.S. economy $97 billion annually in lost productivity, in addition to the $96 billion a year in direct health care costs, according to CMS. Counseling coupled with smoking prevention drugs and devices are among the most cost-effective interventions in the disease prevention arsenal.

The state of Oklahoma reduced its health care costs when it instituted a free counseling program for state employees who smoke. Since initiating the program in 2008, about 5,000 workers have taken up the state’s offer. In addition to reimbursing employees for prescription or over-the-counter products, smokers were also offered a personal “quit coach” available through a toll free telephone line.

The counseling tipped the scale, according to state officials. About 1,155 state workers have quit smoking, saving the state an estimated $4.4 million a year in smoking-related health care costs. Total cost of the program: $930,000 a year — a 373 percent return on investment.

“The coaching, when coupled with medication, doubles the effectiveness,” said Doug Matheny, Oklahoma’s chief of tobacco use prevention services. “It really helps to have both.”

after dropping earlier in the decade.

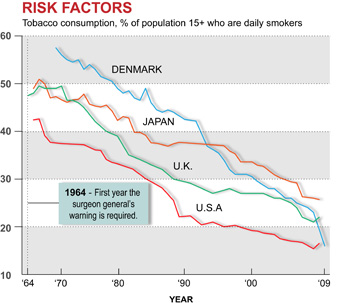

The U.S. has made enormous strides in the 46 years since the Surgeon General declared smoking hazardous to health. In 2008, just 16.5 percent of Americans over 15 smoked, or about 46 million people, which included 4.5 million seniors. That’s not only down from the 42.5 percent who smoked in 1965 (when “Mad Men” and the Marlboro Man ruled the airwaves), it’s below most other advanced industrial nations, including the United Kingdom (22 percent), Canada (17.5 percent) and Japan (24.9 percent).

But a report last week from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said progress against this major driver of rising health care costs may be slowing. A survey of high school and middle school students revealed that teen smoking rates — now 17.2 percent and 5.2 percent, respectively — had stayed essentially flat the past three years despite recession and steadily rising cigarette costs after dropping sharply earlier in the decade.

“Large cuts in funding for state tobacco prevention and cessation programs and the tobacco industry’s continued heavy spending to market its deadly and addictive products” are responsible for the lack of progress, said Marie Cocco, a spokeswoman for the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.

“Large cuts in funding for state tobacco prevention and cessation programs and the tobacco industry’s continued heavy spending to market its deadly and addictive products” are responsible for the lack of progress, said Marie Cocco, a spokeswoman for the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.Between 2008 and 2010, funding for tobacco prevention programs was cut by 21 percent — from $717.7 million to $567.5 million — as states scrambled to fill recession-driven budget gaps with money from the tobacco industry settlement fund that was previously earmarked for tobacco control efforts. Meanwhile, tobacco company promotional spending totaled $12.8 billion in 2006, the latest year for which data are available. The bulk of the spending, according to the advocacy group, has been on price discounting to offset state-imposed tax increases.

It’s Never Too Late

A Rand Corporation analysis of a Medicare demonstration projection estimated the total health care cost savings for the agency exceeded payments for the smoking cessation program within five years. “The cost of these programs may be offset by reductions in medical expenses even when targeting older smokers,” the researchers concluded.

The agency began paying for counseling for seniors already sick with smoking-related illnesses in 2005. It will now pay for four private counseling sessions during two attempts a year for people trying to quit. “The practitioner and patient have the flexibility to choose between intermediate (more than three minutes) or intensive (more than ten minutes) cession counseling sessions for each attempt,” the agency ruled.

But what about people in the prime of life who smoke? They can be seen loitering in alleyways of office buildings and near workplaces throughout the workday.

Both the private and public sectors have mixed records providing benefits for smokers who want to quit. America’s Health Insurance Plans, the health insurance industry’s trade group, estimates that 88 percent of health maintenance organizations offered some type of smoking cessation benefit in 2003, up from 25 percent in 1997. But there’s very little evidence to suggest most smokers take advantage of the programs.

A recent survey of 1,500 health plans by United Benefit Advisors, a trade association for insurance brokers, found just 23.8 percent had active “wellness” programs that encouraged employees to quit smoking. Only 5.3 percent of firms planned to add one, even though the payback in terms of reduced health care costs is immediate.

“It's hard to know what private plans are covering for smoking cessation now, because there are so many of them and benefits vary by employer and carrier,” said Jennifer Singleterry, manager of cessation policy at the American Lung Association. “However, we do know what they should cover: Seven medications like nicotine gum and patch and three types of counseling — individual, group and phone. Tobacco users who want to quit should have access to all of these treatments so they can find the one that works for them,” she said.

Prevention: A Real Bend in the Cost Curve?

State Medicaid programs, which will expand dramatically under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, offer a patchwork quilt of benefits to help low-income people quit smoking. More than a third of people who are on Medicaid or are uninsured smoke, compared to 23 percent for the rest of the population over 18, according to a recent report from the Lung Association.

Yet five states — Alabama, Connecticut, Georgia, Missouri and Tennessee — offer no form of cessation coverage for Medicaid enrollees. Only six states — Indiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Nevada, Oregon, and Pennsylvania — offer a comprehensive menu that includes both counseling and all the intervention products.

Two years ago, a controversial study in the New England Journal of Medicine made headlines by questioning the wisdom of paying for prevention. It pointed out that over 80 percent of all prevention measures — cholesterol lowering pills, mammograms, prostate cancer screening — wound up costing the health care system more than they saved. But these measures did not deal with behavior-related illnesses derived from smoking, obesity and unprotected sex.

Prevention experts responded by noting that even though some prevention and detection measures don’t lower costs, comprehensive counseling programs like smoking cessation do generate savings, and relatively quickly. As insurers, Medicare and Medicaid will have to consider new approaches to major public health problems like the obesity epidemic. Should CMS foot the bill for bariatric surgery for morbid obesity, for instance, if it will reduce the costs of chronic disease? Determining which programs work is one of the new challenges for our health care system.