As the nation digs itself out of the worst recession in 70 years, Americans are coming together to rebuild neighborhoods, raise money to save public services from brutal budget cuts, and make personal sacrifices for the benefit of others. The Fiscal Times will feature some of their stories in our new series, The Path to Recovery.

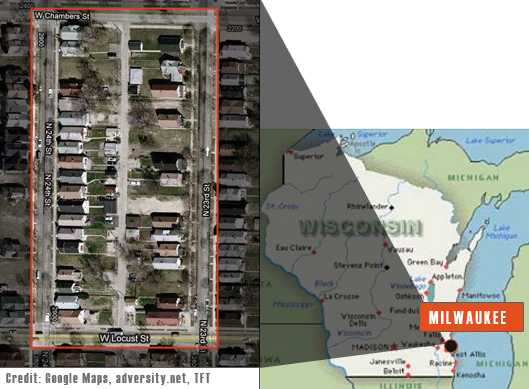

When Nick Toman, 31 and fresh out of law school, first arrived to Milwaukee’s inner-city Amani neighborhood in 2009, it looked like a boarded-up war zone. There were unemployed residents sitting on stoops, endless rows of foreclosed, abandoned, homes, yards that weren't mowed, snow that wasn't shoveled, fallen trees on top of wilted gardens, and garbage that was left to rot. The empty homes were often overrun with squatters, or used as drug dens. One boarded-up home had 36 bullet holes. “It was not uncommon to hear gun shots,” he said.

Toman had come to the neighborhood as a legal fellow though AmeriCorps, a nonprofit organization that pays law students and recent grads small stipends to help underserved communities. In the case of Amani, the group focused on the foreclosures. Toman initially thought he’d be defending homeowners in the neighborhood against foreclosure. But when he arrived, he found that most of the homes in trouble had already been seized by the city and their occupants were long gone. So he decided to put his efforts elsewhere – helping the neighborhood come back. “I wanted to get a grasp on what had happened, and figure out how to improve a neighborhood after foreclosures,” he said.

The foreclosure crisis has hit Milwaukee hard. In 2008, as the housing bubble burst along with the dreams of many Americans, Milwaukee County suffered 6,301 cases of foreclosure — a 70 percent increase from 2006. The crisis had become so dire that in 2010, the city was granted $36 million in federal aid to help purchase and renovate foreclosed homes.

No place was hit harder than Amani, whose low-income residents were perfect targets for the subprime loans that led in part to the economic meltdown. One expert estimated that by 2009, half of all of the houses in that neighborhood had fallen to foreclosure; a quarter were unoccupied. “It was the epicenter of foreclosures in Milwaukee,” said Toman. But the problems weren’t just financial: abandoned homes, a symbol of the recession, drew criminals to the area.

One spring day in 2009, Tramaine Ford, a resident who had recently moved to the, saw two men run towards her home with AK-47s, shooting at each other in broad daylight. One had emerged from an abandoned house next door and the other from a house across the road. “I’ll never forget this day,” recalls Ford, 34. “All I did was scream. I screamed for my kids to get down on the floor. They were afraid to sleep in the house for the first three months that we lived here.”

Ford’s children were 7 and 14 at the time and would often stay at their grandmother’s in a nearby suburban area because they were terrified to sleep at home. “I started to second guess if I should have even bought a house here,” said Ford, whose house had been built by Habitat for Humanity. “But my philosophy is that I was put here for a reason.” When she heard about Toman’s efforts, she decided to help him take back the neighborhood.

Toman first reached out to partners in the area and set up office in The Dominican Center for Women, whose own housing program had helped provide 67 homes to low-income residents. Toman also implored the police to clear houses of squatters and conduct more frequent patrols in the neighborhood. He guided the residents on how to get in touch with the landowners of abandoned properties and linked them to city agencies. “Nick was our backbone,” Ford said. One of Toman’s major triumphs was procuring a $2,000 city grant, which paid for the transformation of a razed lot into a community garden. Dozens of residents showed up to help with the planting, and students from the local Milwaukee School of Engineering pitched in by designing and constructing the raised beds. One of Milwaukee’s poorest neighborhoods now has access to free, healthy fruits and vegetables including tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants. “I had never had a fresh cucumber before,” said Ford. “Now I pick from the garden once or twice a week.”

Toman wanted the homeowners to take ownership of their blocks and lead the revitalization. Ford is known as a “neighborhood captain.” She leads monthly block watch meetings that work with police, fellow neighbors and nearby nonprofits to decrease illegal activity. She worked to get speed bumps to slow traffic on her street. Together with the Dominican Center, Toman and the neighborhood captains raised $10,500 in grants to fund new lighting and paint jobs in at least 19 homes, along with a rotating public art showcase and the community garden. Their efforts are having a noticeable effect: incident reports in Amani have dropped steadily since 2009.

But Toman stresses there is still work to be done. “Criminal activity is down, but it's a block by block fight. It requires a lot of manpower and effort to really change an entire neighborhood,” he says.

That’s a challenge the homeowners are ready to meet. Two years after the shooting incident, Ford says she's comfortable sitting on her porch after dark for the first time. Her kids now feel safe to play in the backyard, skate up and down the street, and walk to the corner store by themselves. “Man, I tell you, this neighborhood has come a long way. I have cook-outs in the summer because crime has decreased so tremendously here,” she says. “It’s not the last you’ve heard of 24th Street.”

Related Links:

Foreclosures at All-Time High—May Rise in 2011 (The Fiscal Times)

Foreclosed and Abandoned: Cities Look for Help (The Fiscal Times)