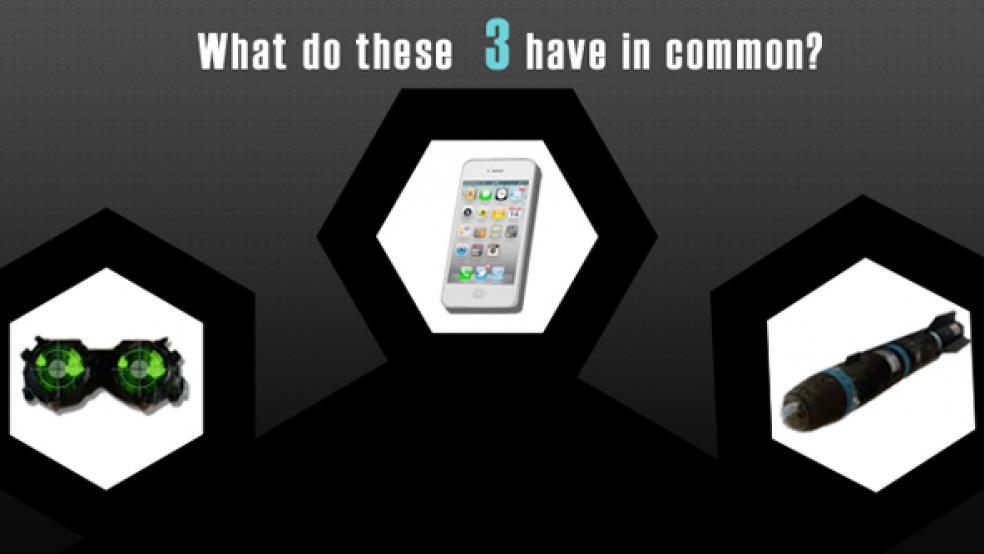

Quick: What do night vision goggles, an iPhone and laser-guided smart bombs all have in common?

Click Here for Rare Earth Slideshow

All three use some combination of elements known as “rare earth metals” which are a key component in iPods, Blackberries, plasma TVs, smart bombs, hybrid car batteries and heat-resistant military equipment. These products and many more could vanish or soar in value if new rare earth reserves aren’t tapped. The reason — China currently has a lock on up to 97 percent of the world’s supply of rare earth minerals and has threatened to use this geologic advantage as a negotiating tool, causing a race to restart a U.S.-based industry in the name of national security, possibly with federal subsidies.

What Is It?

At the dawn of the electronic era, these metals became useful in luminescent tubes and in magnets that maintain strength at high temperatures. Despite the name, rare earth metals are not technically “rare” nor “earth” in the classic sense — they’re a bit like the chemical version of the Holy Roman Empire, which, as the old joke says, was none of the three.

They were forged in the explosion of supernovas some four or five billion years ago and deposited in the crust of a cooling ball of minerals that hardened into the planet we inhabit. Various elements of the series are scattered widely throughout most of the globe, but located in deposits above two percent purity in only a handful of spots. The term refers to a collection of elements on the Periodic Table grouped in “the lanthanide series” from numbers 57 through 71, and also includes scandium and yttrium. (There is no geological connection, though some may consider them equally ancient: the 1970s Motown super group, Rare Earth, had a chart-topper with “I Just Want to Celebrate.”)

How We Get It

Whenever the word “shortage” is in play, of course, somebody is making huge profits as demand exceeds supply. Mining companies from Australia to California’s Ivanpah Valley are now in a quest to mine and refine a new batch of Rare Earths — many from old iron diggings once thought exhausted.

Earth is an antique term of geology used to refer to a metal that could not be dissolved in water or purified through the low-heat smelters that were used three hundred years ago. The ion structures still make them difficult to separate from each other without an intense chemical regimen, which is part of the reason why reconstituting a home-grown industry has been so difficult. The refining process often leaves behind a hazardous mess, as most tailings include the radioactive element thorium. Almost all the commercial Rare Earths in the world used to be mined from a pit in remote Mountain Pass, California, but that mine — and the whole American industry with it — was shut down because of a radioactive leak in 2002.

Without the same rigor to its environmental reviews, China began large-scale mining in Sichuan Province the early part of the 2000s. In the midst of a dispute over fishing boundaries with Japan in September 2010, China halted the export of Rare Earths to its historic Pacific Rim rival. The prices of cerium (used in glass polishing and catalytic converters) increased a thousand fold, triggering a mini-crisis in those businesses. An Australian company called Lynas is now building a massive new refinery in Malaysia to handle the expected peak in demand. Analysts have said the price in Rare Earths could skyrocket before the market stabilizes, and especially if further Chinese trade restrictions take effect.

The U.S. Stake

There has been some discussion of how the U.S. military might deem Rare Earth minerals a “strategic” resource, much as uranium was treated in the 1940s and 1950s, and oil was in the 1910s and 1920s (no-bid leasing of petroleum set aside for the U.S. Navy was at the heart of the Teapot Dome scandal that clouded the presidency of Warren G. Harding). This would mean triggering the Defense Production Act, a Korean War-era law that helps speed up acquisition of materials necessary in combat, which would force businesses to sign deals with the government and give the White House direct oversight of the industry, noted Reed Livergood of the Center for International and Strategic Studies in a paper this year. Rare Earths would qualify because of their use in weapons technology.

A subsidiary of Molycorp, Inc., a mining company in Colorado, is now spending $531 million to build a new separation plant at Mountain Pass, a job that should be completed by January of 2012. But part of the problem is that the mine only produces about half of the Rare Earths in the series — cerium, lanthanum, samarium, gadolinium, neodymium, praseodymium and europium. This last one was a major product of the mine during its run from 1949-1998, as it is a substance used in the red phosphor in the color TVs enjoyed so much by the world in this era.

The company says it has developed new and cleaner methods of chemical separation — the exact details of which it does not disclose — and also has plans to bring the production up to 40,000 metric tons per year within two years. “The actual hardrock mining is not the principal chore,” said spokesman Jim Sims. “Ninety percent of what we do in capital costs and time and energy is the actual separation,” which is partly done through bathing in hydrochloric acid and creating mineral salts. These finished Rare Earth metals are not traded on the open market but produced according to customized orders; each mineral is priced separately based on investor index reports. Chevron, which still owns much of the property, is still responsible for cleaning up the old pipeline spill, said Sims.

The St. Louis company Wings Enterprises is also seeking to reopen the defunct Pea Ridge mine in Missouri, which was originally dug out as a pig iron mine for Bethlehem Steel in the 1950s. The ore happened to contain Rare Earths. Wings president James Kennedy is currently lobbying Congress to build a federally-operated Rare Earth refinery near the banks of the Mississippi River. But the Government Accountability Office estimated last year that bringing a U.S. industry back in full would take anywhere from seven to fifteen years, noting also that the Mountain Pass mine does not contain “substantial amounts of heavy rare earth elements, such as dysprosium, which provide much of the heat-resistant qualities of permanent magnets used in many industry and defense applications.”

Related Links:

Commodity Crunch: Forget Gold, Copper is King (The Fiscal Times)

Investors Get Picky in Rare Earth Race (CNBC)

My Visit to an American Rare Earth Metals Mine (Popular Science)