Republican Blake Farenthold, a small time radio show personality and Tea Party favorite in southern Texas, scored a major upset last November when he defeated 14-term Democratic House member Solomon Ortiz Sr. by a mere 799 votes. His victory in the marginally Democratic 27th District near the Gulf Coast was even more remarkable because he weathered the embarrassment of a widely disseminated photo of him in yellow duck pattern pajamas with a scantily dressed woman.

Farenthold arrived in Washington from Corpus Christi two weeks later with a hefty campaign debt and a seat that the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee declared a “must win” for Democrats in 2012. But not to worry. Though Farenthold had attracted a meager $18,850 in contributions from corporate and special interest political action committees before the election, he collected more than four times that amount, or $77,830, after the election.

Joe Walsh, a venture capitalist from the Chicago area, had a similar experience: Almost nobody gave him much of a chance of winning against three-term Democratic Rep. Melissa Bean in Illinois’ 8th District. Compounding matters for Walsh: The Republican Party and special interests steered clear of him after his Evanston, Ill. condominium went into foreclosure, and a former campaign manager sued him for unpaid wages.

But Walsh's fortunes changed dramatically after he scored a stunning victory with the support of retirees and tea party activists, according to an analysis of federal campaign finance records by the Center for Responsive Politics and The Fiscal Times. While Walsh attracted only $10,799 in PAC funding before the election, he raised an additional $50,400 between the election and December 31. Both he and Farenthold raised more than 80 percent of their overall PAC contributions in the weeks following the November election – which helped to put a healthy dent in their sizable campaign debts.

Many GOP freshmen ran as fiscal conservatives and political outsiders, vowing to change politics as usual in Washington. But that was before they accumulated substantial campaign debt and began worrying about raising money for the next election. Now they have aggressively turned to their party organization, K Street lobbyists and other special interests for financial assistance.

“It’s a time honored Washington trend – whether they are tea party people or not – to run against Washington and put their hands out to lobbyists once they get to Washington,” said Nancy Watzman of the Sunlight Foundation, which tracks fundraising by members of Congress. “It’s interesting when people have so forcefully spoken out against it.” Farenthold's chief of staff said this week that he doesn't think "the GOP elected in this cycle are contradicting what they said” during the campaign.

“Change in Washington means change in the government and spending and reducing the burdensome hand of government,” said David Lasseter, the chief of staff. “We are open to accepting financial support and contributions from PACs that are supportive of the Congressman’s stance or viewpoint whether that is politically, socially, budgetary or whatever.”

Farenthold still owed $156,643 as of last Dec. 31, according to Federal Election Commission reports. Walsh – who could not be reached for comment -- finished the year still owing $361,740. Overall, the 87 House GOP freshmen were in debt to the tune of $11.9 million, or an average of $137,296 per member, according to Center for Responsive Politics-The Fiscal Times figures. Rep. Francisco Canseco, R-Texas, reported the largest campaign debt, of $1.1 million. By contrast, the nine Democratic freshmen reported average campaign debt of $73,493.

Joanna Burgos, a spokesperson for the National Republican Congressional Committee, characterized the post-election surge in PAC giving as business as usual--little different from previous election cycles – with campaign debt retirement a major concern.

“We have seen a lot of [House] members making their calls and having their events, and they are taking their campaigns very seriously and we do expect them to do very well in the first quarter” of this year, she added. First quarter campaign finance reports are due to the Federal Election Commission by the end of Friday.

During the 2010 campaign cycle, the House GOP freshmen raised $85.5 million in contributions from the business and economic sectors, insurance companies, health care companies and agribusiness, according to the Center for Responsive Politics/Fiscal Times analysis. Of that amount, at least $4.1 million was raised in the weeks following the election.

Among the industry groups and PACs that rushed to shower contributions on the newly elected GOP members were the American Bankers Association, which gave $158,500 through its PAC; the National Beer Wholesalers Association, which gave $132,000; the National Association of Insurance & Financial Advisors, $124,000, AT&T Inc., $118,500; the American Hospital Association, $87,000; Comcast Corp., $66,500, and the National Auto Dealers Association, $55,500.

“Giving after the election has pretty much become SOP – standard operating procedure,” said Meredith McGehee, policy director at the Campaign Legal Center in Washington. “If you’re a player in the Washington money game you have to make sure that you get access [to new members of Congress]. And it’s a means of both helping successful candidates retire their debt as well as start leading them onto the path of true incumbency, meaning a successful reelection.”

"That doesn’t mean everyone does it,” she added. “It just means that’s an arrow in the quiver that you can use – particularly if you feel like the candidate is either relevant based on location or based on committee assignment or based on pet issues that they’ve talked about.”

Peter E. Garuccio, a spokesman for the American Bankers Association, said that “ABA gives, and has always given, to members of both parties, including for debt retirement after elections are concluded.”

“Keep in mind, there are contribution limits,” he added. “All of our contributions are a matter of record.”

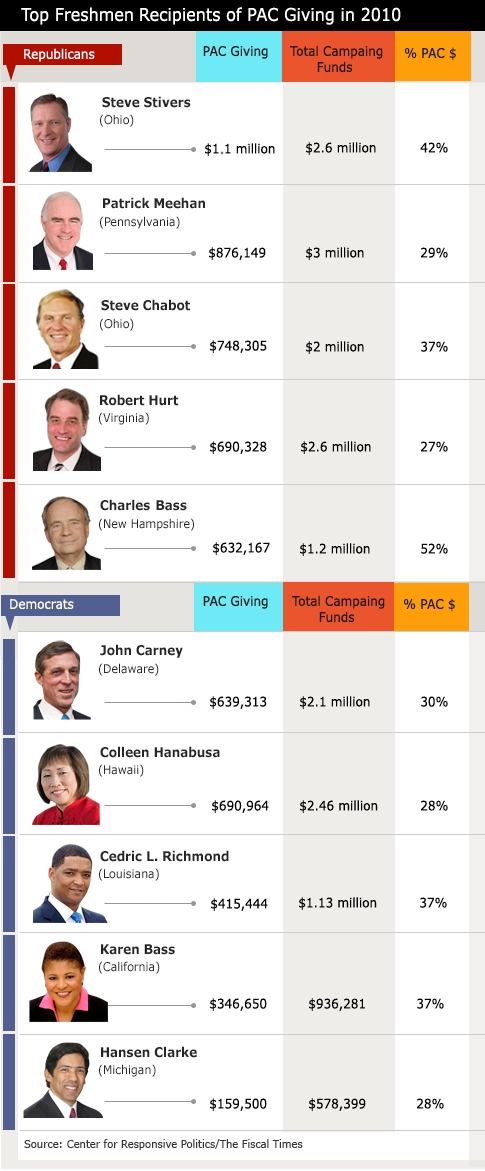

House GOP freshmen who raised the largest share of PAC money throughout the 2010 election cycle were Reps. Steve Stivers, Ohio, who raised $1.1 million of his $2.61 million campaign war chest from industry and special interest PACs, and Patrick Meehan of Pennsylvania, who received $876,149 of his $3 million of total campaign contributions from PACS and other special interest organizations.

Stivers sits on the House Financial Services Committee, a key overseer of the banking and financial industry, while Meehan is a member of the Homeland Security, Transportation and Oversight and Government Reform Committees.

Others in the Top 10 included: Steve Chabot of Ohio, $876,149; Robert Hurt of Virginia, $690,328; Charles Bass of New Hampshire, $632,167; Cory Gardner of Colorado, $603,568; Dennis Ross of Florida, $559,539; Kevin Yoder of Kansas, $448,525; Jaime Herrera of Washington State and Daniel J. Benishek of Michigan, $523,403.

The nine Democratic freshmen also fared well in attracting PAC money. The Democrats raised about a quarter of their overall $13,067,538 in campaign funds from PACs, or $3.4 million. For example, Rep. John Carney of Delaware relied on PACs for $639,313 of his $2.1 million campaign war chest; Rep. Colleen Hanabusa of Hawaii turned to PACs for $690,964 of the $2.46 million she raised; and Cedric L. Richmond of Louisiana received $415,444 of his $1.13 million of campaign funds from PACs.

Among Republican freshmen, Farenthold and Walsh benefitted the most from industry and special interest group’s post-election stampede by picking up the vast majority of their PAC contributions, or eight of every ten dollars collected. Others, including Reps. Raul Labrador of Idaho, William Flores of Texas, Vicky Hartzler of Missouri , picked up a quarter to 40 percent of their overall PAC contributions after the election.

Labrador was one of the Tea Party’s biggest success stories in the November election. The Cuban-born immigration lawyer defeated Blue Dog Democratic Rep. Walt Minnick, although he was outspent by Minnick by nearly five to one. Shortly after the election, Labrador attended at least three fundraisers including a debt retirement reception, a meet-and-greet and a dinner, according to the Sunlight Foundation. Each of the events was coordinated by Winfrey & Co. Political Fundraising, a Republican consulting firm. He raised $84,371 in PAC donations before the election and $66,950 after the election.

Some of his largest PAC donations after the election came from the National Rifle Association of American Political Victory Fund with $10,900 in December and February, a review of FEC records indicates. The American Bankers Association PAC and the American Crystal Sugar PAC each donated $5,000. Other late contributors to Labrador’s war chest included the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which backed Minnick in the race.

Flores, a former oil and gas company CEO, ousted veteran Democrat Chet Edwards in a conservative-leaning central Texas district after denouncing “career politicians who care more about serving special interest than serving the people.”

Flores attracted plenty of PAC money during the campaign -- $209,542, including a chunk from the oil and gas industry – but he ended up with a $730,872 campaign debt. Between the election and Dec. 31, PACs gave Flores’ campaign committee an additional $131,672, or 39 percent of his total PAC funds.

By then he had landed assignments on the House Natural Resources, Budget, and Veterans’ Affairs committees. An array of oil and gas industry groups including Anadarko Petroleum, ConocoPhillips, Exxon Mobil, and Marathon Oil were among those that kicked in. Flores’s office declined this week to comment on his financial situation. But he continues to scramble for contributions, as he did in a Feb. 11 fundraising letter requesting contributions to help retire his campaign debt while vowing to combat “the exploding federal debt” and “overreaching regulation.”