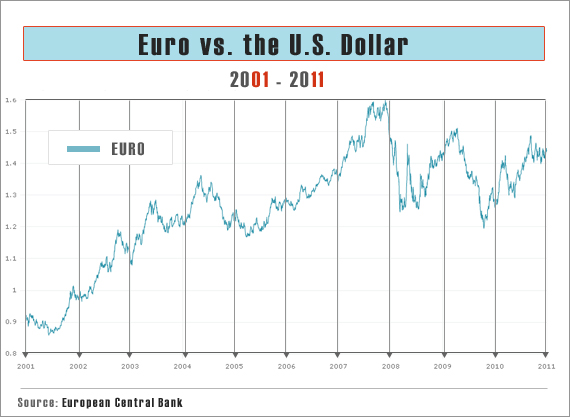

The millions of American tourists traveling to Europe this summer face a rude awakening as soon as they clear customs: The dollar doesn’t go very far against the euro. Recently, it’s been trading in a range near $1.44 to the euro. (Ten years ago, a euro could be bought for just 0.90 cents.)

But since both the U.S. and Europe are struggling with massive and far-reaching fiscal problems, it seems odd that the euro continues to trounce the greenback. In the past year alone, the dollar has slipped 15 percent against the currency of the 17 nations in what’s known as the eurozone. So what’s behind the surprising strength of the euro? The answer is complicated, but a few major factors loom large in accounting for the disparity.

Interest Rates. Investors still generally flock to the dollar's perceived safety in uncertain times. But with interest rates on the dollar near zero, they tend to look to currencies yielding higher returns if they smell a recovery. The euro is one of those currencies.

“Investors naturally seek to invest in currencies that best combine yield with safety of funds and for much of the past few years, the euro has held a distinct advantage over the dollar,” says Scott Boyd, an analyst at OANDA, a currency trading firm based in Toronto. “During the past recession, the Fed reduced the benchmark U.S. interest rate to a mere 0.25 percent to encourage spending. In the eurozone, the rate never fell below 1 percent.”

Debt and Deficits. In addition to differences in monetary policy, “underlying concerns about U.S. debts plus very large U.S. current-account deficits suggest dollar depreciation is more likely than appreciation,” says Jonathan David Kirshner, a Cornell professor and author of Currency and Coercion: The Political Economy of International Monetary Power.

And while the EU certainly has its own debt problems, they differ in structure from those of the U.S. German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble emphasized in a radio interview Monday that for now, the EU debt crisis remains contained to just a few countries and “the United States has higher debts than even the most difficult countries in the euro zones.”

Although some may disagree with Schaeuble's assessment, the consensus perception is still that the EU debt crisis is bad, but the American one is worse. “Certainly the current debt crisis has had a detrimental impact on the euro, but this has been muted somewhat by concerns that the U.S. could be slipping back into recession,” says Boyd.

Diversification of Sovereign Wealth. Government-owned (i.e. sovereign wealth) funds have been diversifying their once-straightforward portfolios in recent years, a shift that has benefited the euro and hurt the dollar. As Martin Feldstein, a Harvard professor and chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors under President Reagan, explained in the Wall Street Journal earlier this month: “While [governments] initially viewed these funds as traditional foreign exchange reserves to be invested in highly liquid U.S. Treasury bills, they gradually realized that these large funds should be treated as investment assets and diversified accordingly.”

The Road Ahead

Despite these factors currently working in the euro's favor, it remains to be seen if the currency can sustain its position.

“Europe’s fiscal problems threaten to undermine the euro in that they might undermine confidence in the larger European economic project,” says Kirshner. “If the Europeans come up with something that looks like a ‘grand bargain’ to get [their] debt problems on track, the euro will appreciate. If [they continue] to kick the can down the road, the euro will continue to be vulnerable.”

Others are far less optimistic. “Given the degree of uncertainty facing the eurozone region, it is hard to image a scenario that favors the euro exchange rate,” says Boyd.

On Sunday's Wall Street Journal Report, former Reagan Budget Director David Stockman went a step further, telling Maria Bartiromo that the debt problems in the EU are too big for the currency to survive in its current state. “We're going to see a structural change in the euro. I just don't see how it continues,” he predicted.

As for the dollar, its weakness may be bad for American tourists, but it could be a positive for an American economic recovery. It makes exports cheaper for foreign consumers and that could provide a much-needed boost to U.S. manufacturers.