This story was updated on August 25, 2011

On the heels of an earthquake felt from New England to the Carolina, the East Coast is bracing for Hurricane Irene, which could be a major Category 4 storm with winds upwards of 130 mph. That could mean billions of dollars in property damage that further push up insurance premiums.

Hurricane Irene will be only one of many catastrophes this year to slam insurance-company reserves. The recent earthquake in Virginia, the April tornados in North Carolina, Oklahoma, Texas, and other states; the East Coast winter storms last January; flooding in Southern California in December 2010; wildfires in Texas; and heavy rains and hail in the Midwest are adding to the long list of recent catastrophes that insurance companies are paying for. “If you combine the winter storms that we’ve had and other things that have gone on earlier this year, it’s been a very active year, not only in the U.S., but worldwide,” says Don Griffin, vice president at Property Casualty Insurers Association of America. “This may cause a gradual increase in premiums.”

In 2010, damage from wind and hail alone cost State Farm $3.2 billion — 101,000 claims from Illinois, Texas and Oklahoma alone. The average cost per claim in Oklahoma was $13,893. “This has been a pretty busy year,” says State Farm spokesman Jeff McCollum. “And it’s just the start of the storm season.”

To calculate premiums, Griffin says, insurers typically look at the average risk in a three- to five-year time horizon for property loses, rather than reacting to one major event.

“Any kind of severe weather tends to get insurance companies nervous,” says Amy Bach, executive director of United Policyholders, a consumer advocacy group. “When they get nervous, their number crunchers take another look at what their exposure is and whether they’re charging enough and that may lead to rate increases.”

Higher premiums aren’t the only way insurance companies protect their bottom lines, according to Bach. Among them: raising deductibles, low-balling the damage assessment to the property to stay under the deductable, or cutting insurance categories altogether. All of them mean higher total costs to consumers. “The laundry list is getting longer of what is not covered,” says Bach. “It used to be flood, now it’s flood and hurricane and earthquake.”

That could leave homeowners with fewer options: They can either turn to state-run insurers, which are growing fast in areas that have been hit by natural disasters, or find separate, private insurers for each disaster category. In California, for example, homeowners might need four separate policies: homeowners, flood, earthquake and hail. “It’s a waste. You’re paying for four insurance companies’ overhead, four offices, four mailings, four secretaries, it’s ridiculous,” Bach says. “My fear is the insurers have gotten so removed from their customers’ needs, that they’re undermining the whole system and creating pressure for public insurers and public options.”

in the area, we insured 25 and that’s too many

for us. Let’s insure 15 instead of 25 homes.”

For example, the number of policies written by Citizens Property Insurance Corp., a government-funded nonprofit in Florida, ballooned after the tropical storms and hurricanes of 2004 and 2005, rising from 820,000 in 2003 to nearly 1.3 million today. That’s because so many private insurers opted out of hurricane coverage. Citizens now claims they don’t have reserves available to cover losses if a massive storm were to hit the state, and a bill was recently presented in the state Senate asking for a 25 percent rate increase. And with state budgets already fragile, the gap between the risk and reserves of public insurance companies is a growing concern.

Insurers do need to find ways to limit their exposure, concedes Griffin, of the Property Casualty Insurers trade group. “Companies might decide to not to insure certain areas, or insure less in certain areas, or less homes after a major event,” he says. “Companies might say, look, out of 100 houses in the area, we insured 25 and that’s too many for us. Let’s insure 15 instead of 25 homes.”

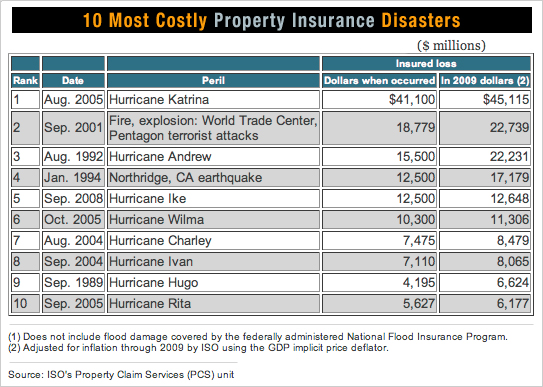

Both homeowners and insurers are still feeling the lingering aftereffects of Hurricane Katrina. Depending on the location, some property rates increased by 25 to 50 percent as a result of Katrina, according to Griffin. ”Hurricane Katrina, Wilma and Rita collectively caused $62.5 billion of insured losses in the property casualty and insurance industry,” says Griffin. “It certainly had an impact in our industry as far as premiums and the reserves we had on hand.” Adds State Farm’s McCollum: “Katrina changed a lot of things for a lot of people in the business.”

Bach says that after Katrina, insurance companies denied coverage in some cases by arguing that flooding, which they don’t cover, caused the damage, not the wind. “The insurance companies won most of the litigation,” says Bach, “but to make sure they would win all of it the next time around, they went back and tightened the wording.”

Scientists who say that global warming is responsible for the uptick in volatile weather warn that extreme weather conditions are only going to get worse. A report by the U.S. Global Change Research Program found that precipitation has increased 5 percent over the past 50 years and that storms are “likely to become strong and more frequent.” FEMA reported the highest number of weather-related disasters in its history in 2010. “Companies plan way ahead and try to protect themselves by buying reinsurance and bolstering cash reserves,” says Griffin. “This might mean raising premiums.”