When Robert and Ashley Holbrook looked for their first house this summer in Evanston, Illinois, they had a key criterion: buy at a price that would qualify them for a mortgage based on Robert’s $30,000 stipend as a doctoral student. Ashley, who works as a nurse, earns “a lot more” money, and with their combined income they could have gotten a loan for a house worth more than $200,000. Instead, they settled on a foreclosed condominium that they bought from a bank for $85,000.

Meet the new first-time buyer. They’re younger, more likely to be single, signing for smaller loans than their predecessors, putting more money down, getting fixed-rate mortgages, and planning to stay in their houses longer. What they saw during the housing collapse has turned them into a cohort of financially conservative buyers who could help prevent another cycle of bubble and burst.

Zele Avradopoulos, 43, is one of those who said no during the buying euphoria. In 2006, she looked at a few houses out of curiosity, but as a small-business owner didn’t feel financially stable enough to get a loan. A realtor at the time told her not to worry — she could get a no-money-down loan for a $300,000 house and wouldn’t have to verify her income. “That’s what got me going, ‘no, this is just not right,’” she says.

Instead she waited. In August, she bought a two-bedroom condominium in the upscale town of Hingham, Massachusetts. She negotiated a 15 to 20 percent discount on the asking price and used her savings to front 50 percent in cash.

That hefty down payment fits first-timer trends — the amount put down has doubled since the height of the boom, from a low of 2 percent in 2006 to 4 percent today, according to the National Association of Realtors (NAR). Entry-level buyers usually put down less money than do repeat buyers because many first timers take advantage of Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loans, which allow down payments of as low as 3.5 percent for those who qualify. Those who can’t get an FHA loan still can keep their down payment small by buying private mortgage insurance (annual premiums run between 0.5 percent and 1 percent of the loan amount) or getting a second mortgage that covers part of the down payment, though at a higher interest rate than the first.

Compared with 10 years ago, first-time homebuyers are more frequently single (18 percent in 2001 versus 22 percent today) and a little younger (average age of 31 in 2001 versus 30 now). And fewer of them are married couples with children — in 2001, they made up 33 percent of first-time home buyers; today their share is only 26 percent.

Photo Gallery: Starter Homes in 10 Real Estate Markets

Entry-level buyers also are more likely than before to use their own savings for the down payment — 57 percent did so in 2007 versus 63 percent in 2009, according to a report last year by the National Association of Home Builders. There’s even a growing group who are saying no to the banks and are paying all cash for their first house — their number rose from about 7 percent in 2009 to 11.4 percent so far in 2011, according to the NAR.

Banks, of course, are demanding more: higher credit scores, more documentation, and more up-front cash. Increasingly, first-timers are meeting that demand for bigger downpayments by combining their savings with draw-downs from that oldest of banks: mom and dad. The proportion of first timers using a gift from a relative increased to 27 percent in 2010, up from the historically typical rate of 22 percent in 2009.

Twenty eight-year-old Julie Watson, for example, closes in early October on her first house, a two-bedroom bungalow in Jacksonville, Florida, that she got for $107,000. She’s using an FHA loan (as did 56 percent of entry-level buyers last year), and put down 5 percent. Half of that came from her savings, and half from her parents.

In another trend, parents are taking the bank’s place -- making loans to their children themselves, says NAR spokesperson Walter Molony. That’s being driven largely by a volatile stock market and low yields on CDs and savings accounts. Parents get a better return on their investment while helping their children bypass the high hurdles of today’s lending process.

The Holbrooks, for example, qualified for a loan from Wells Fargo but chose instead to take out a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage with Robert’s father. Lucky thing too — his father took the money out of stocks just before the market crashed in late July.

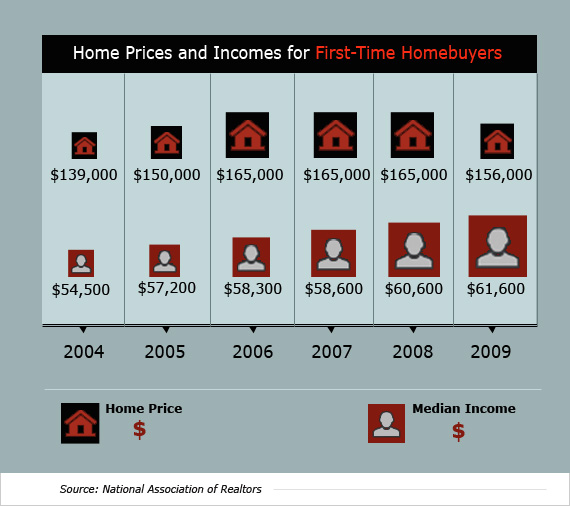

The Holbrooks, Watson, and Avradopoulos also stuck with fixed-rate loans, just like 95 percent of today’s first-time buyers (up from 71 percent in 2006, according to the NAR). And like others in the current class of entry-level buyers, they’re avoiding extreme levels of debt. In 2006, first timers had a median income of about $58,000 but bought homes nearly three times that at an average of $165,000. In 2009, those figures reversed--buyers now have higher incomes on average ($62,000) but buy less expensive homes ($156,000).

But while the current crop of first-time buyers could help stabilize the market, their numbers appear to be shrinking. They made up a record 50 percent of all buyers in 2010 but just 32 percent for August, according to the NAR — largely due to the end of the federal $8,000 first-time home buyer credit program last September.

The drop in first-timers could lead to pressure for more incentives to get people buying. But there’s no indication of that so far. “Of course the more people we have buying houses, the better the near-term conditions are,” says Celia Chen, a housing economist at Moody’s Analytics. “But I think we want to be careful about encouraging too many people to become homeowners. That’s what got us into this mess.” Housing, she says, will recover when the economy starts producing more jobs and gives buyers confidence.

For the NAR’s Malony, housing and first-time buyers won’t come back until banks stop making what he sees as overcorrections to compensate for loose lending during the bubble. He notes that default rates for loans originated since the crash are only 1 percent, compared with a historical average of 2 to 3 percent. That means that they’re lending only to the “cream of the crop,” he says. The NAR projects that if all creditworthy buyers were able to get loans, sales would be 15 to 20 percent higher than they are now.

But even without bank road blocks, getting potential first-time buyers into the market is harder now because of what many of them saw during the crash. “I had a lot of friends who bought houses before the bubble burst,” says Watson. “They all have homes that aren’t worth as much as they paid for them. One of my concerns was buying a house I couldn’t afford or that would be worth less than I paid for it.”