Baruch College in New York boasts it is the largest accredited business school in the U.S., with more than 18,000 undergraduate and graduate students enrolled this fall. But when the school’s accounting department was put on probation in 2005 for not having enough qualified professors, neither Baruch nor the organization that accredits it made the red flag public.

John Elliott, dean of Baruch’s Zicklin School of Business, which is part of City University, says the school hired more faculty members and the probation was lifted later that same year. He says the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International, the Tampa-based nonprofit that oversees the 500 largest U.S. business schools, helps identify weaknesses so they can be addressed promptly. But Elliott says increased disclosure would subject universities to unnecessary public ridicule. “It’s not clear to me how that would really help families and students make a better choice when things are already on the road to being remedied,” he says.

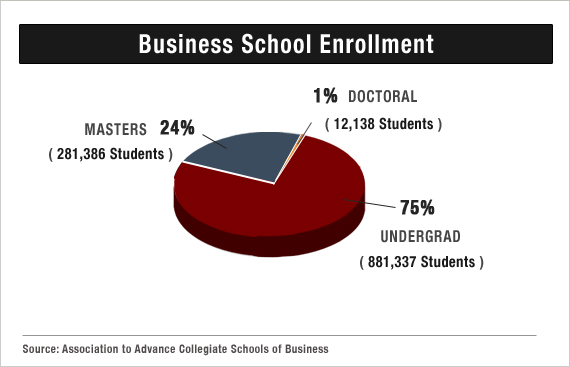

A fifth of the business schools reviewed annually by the AACSB – accounting for more than 1.2 million students in both undergraduate and graduate programs -- are put on probation for problems with faculty, insufficient funding, or other academic issues. But the information rarely becomes public and many prospective students remain in the dark even as tuition bills climb. Rather than disclosing all its decisions, the AACSB issues news releases only about schools earning accreditation or passing their five-year renewal.

“When we find shortcomings, we don’t think it’s important to publicize that,” says Andrew J. Policano, dean of the University of California at Irvine School of Business and an AACSB board member. “We are trying to help the school through a rough patch, and that’s not something we want to draw a lot of attention to.” Policano says students can find a wealth of information on business schools elsewhere through various rankings and guidebooks.

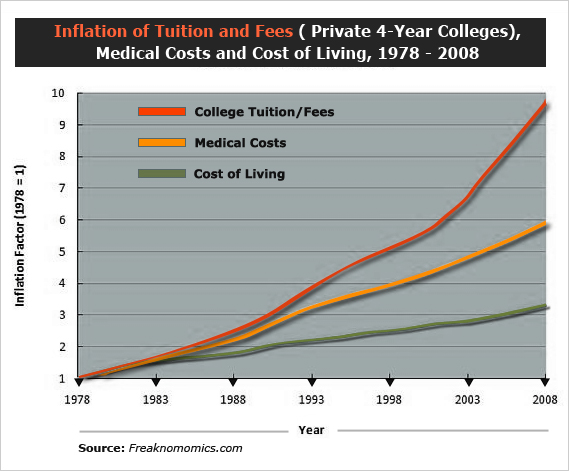

The lack of disclosure is out of step with a growing demand for increased transparency in higher education from many federal education officials and consumer advocates. “The call for consumer protection is getting stronger and stronger as tuition costs climb higher and higher,” says Margaret Miller, an education professor at the University of Virginia who has advised the U.S. Department of Education on accreditation matters.

Overall, undergraduate tuition at private institutions has shot up 70 percent since 2001, to an average of more than $27,000 annually, according to the College Board. Public tuition more than doubled over the same period. What’s more, a tough job market has made it harder for graduates to pay off their student loans. Average debt for graduating seniors with student loans in 2009-10 reached more than $22,000 at public schools and $28,000 at private universities, College Board data show.

Miller says business school applicants should be able to read the key findings from accreditation reports and see a list of schools on probation. Most other accreditation agencies for universities are required to disclose all their decisions — good and bad — and what specific problems led to probation or revocation. A federal rule mandates any accreditation decisions be made public “within 24 hours of notice to the institution or program.” Regional accreditation groups carry out the primary task of reviewing universities as a whole.

The AACSB falls outside the federal requirement because its specialty accreditation is optional for business schools and does not affect their eligibility for federal aid. But most business schools seek AACSB approval as a badge of quality. The group, founded in 1916, reviews an entire business school every five years, and as part of that process, checks faculty numbers and credentials and the effectiveness of the curriculum. It begins with the college’s self-assessment followed by a campus visit from a three-member team of business deans.

Academics and some members of Congress have been calling for reform of the overall accreditation process. Critics contend the system relies too much on self-regulation by university deans and suffers from a lack of transparency. “There’s lots of information prospective students could benefit from in the accreditation process, but they don’t have access to it. They’re not letting you compare one institution to another, “says Andrew Gillen, research director at the nonpartisan Center for College Affordability and Productivity in Washington. “Schools don’t want universal benchmarks where you can say this school is better than that school,” Gillen says.

Larry Ellman, who earlier this year helped his daughter, Alexa, research several business schools before she made her college choice, says parents and students deserve to know what accreditation teams turn up, particularly since many college rankings don’t focus on specific programs. “I wouldn’t be pleased if my daughter was going to a school that was put on probation for not having enough faculty,” says Ellman, a property management executive in Weston, Fla. Alexa is a freshman now at the University of Pennsylvania’s (fully accredited) Wharton School of Business studying accounting and finance.

Officials at AACSB say their system of peer review is extremely rigorous and additional disclosure could prevent some schools from being candid in self-assessments. In September, the AACSB board discussed increasing transparency in response to the ongoing accreditation debate and reaffirmed the status quo, says Jerry Trapnell, the group’s chief accreditation officer and a former business dean at Clemson University.Trapnell says disclosing a school’s shortcomings could put that institution at a competitive disadvantage and exacerbate the problem. “All of a sudden students don’t want to go to that school because of a blip on the screen,” he says. “People can blow things out of context and we think it’s fair to give schools a chance to resolve these problems without blabbing about it all over the world.”

Trapnell recalls only four schools losing their business accreditation in the past 30 years. It’s more common for a school to be put on probation and get one to three years to address any deficiencies. Of the schools placed on probation, Trapnell says, the most common problem is a lack of qualified faculty caused in part by budget cuts. “Schools have dismissed faculty, class sizes have gone up, and existing faculty have picked up larger loads,” Trapnell says.

Business degrees, which cover a wide range of disciplines from marketing and management to finance and accounting, remain highly popular. More than 20 percent of all bachelor’s degrees are conferred in business fields. But recent studies show business majors lag the field in core curriculum proficiency. In Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses, a book published earlier this year, authors Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa found that business majors made the smallest gains during the first two years of college on a national test of writing and reasoning skills. Business students also scored lower than their peers in every other major on the GMAT, an entry exam for master’s degree in business administration (MBA) programs. The authors said a major reason was a lack of academic rigor in business school curriculum.

Trapnell of AACSB says there are legitimate concerns about the quality of business education. He says the group is continually reviewing its standards to ensure schools are “driving exceptional learning from start to finish.”

Jerry Zimmerman, a professor of business administration at the University of Rochester and co-author of a 2005 paper “What’s Really Wrong with U.S. Business Schools?” commends AACSB for shifting away from old-fashioned methods of counting library books and computers as quality measures and asking schools to assess student learning. But he says accreditors don’t go far enough, instead leaving it up to each school to develop its own assessment. He also criticizes AACSB for not publicizing school results, particularly on crucial factors such as the number of qualified faculty.

Not everyone in the business school world subscribes to the AACSB approach. An accreditation group for smaller business schools discloses its adverse decisions and lists what deficiencies turned up. Steve Parscale, a program director at the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs in Overland Park, Kan., says “accreditation is a fantastic tool to let people know how a school is doing.”