There’s an ugly fiscal stew brewing in Scranton, Pennsylvania – and it may be months or years before the city can purge itself of the impact. Even then, the stink is likely to last.

The city’s mayor, Chris Doherty, a Democrat, has slashed wages for nearly 400 public employees to $7.25 an hour, the federal minimum wage, because there’s not enough money in city coffers to pay those workers their usual salaries. The city is some $16.8 million in the hole based on its current fiscal year budget.

As expected, public workers’ unions are fighting back. Last week they filed a lawsuit seeking their full pay, and a local judge agreed with them, ordering the city to pay the full wages even though the mayor said the city is nearly broke. But the much-reduced paychecks went out anyway – and now the police, fire and department of public works are saying they’ll again go to court to hold Doherty in contempt of court.

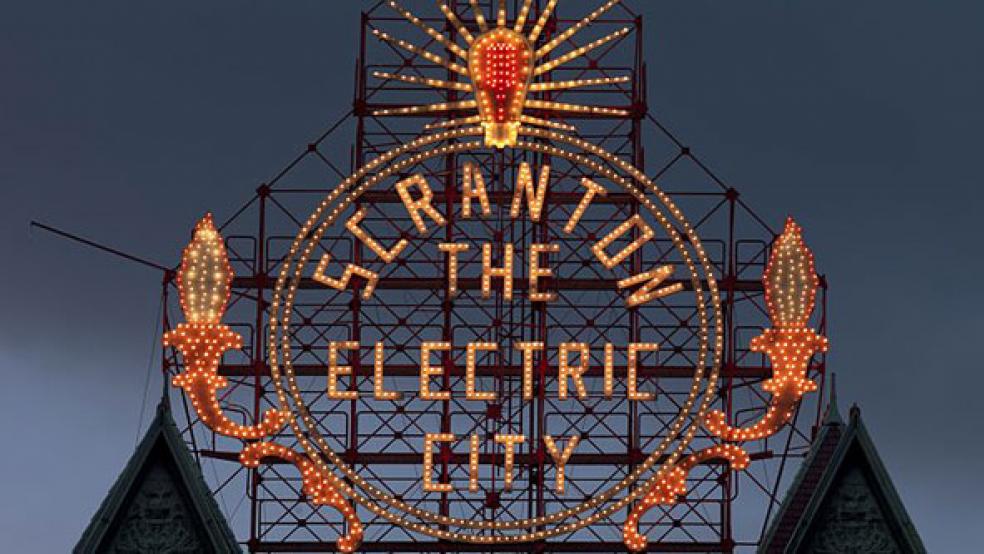

In this northeast corner of Pennsylvania, a place hammered by the real-estate slump and the recession, the mayor and its city council have long been at odds over how to raise capital. After its history of industrial production, Scranton has seen its population steadily decrease over the years. Area hospitals and universities provide a hefty portion of the employment opportunities today, but they alone can’t carry the revenue-raising burden.

Doherty wanted to hike taxes – proposing a recovery plan that includes 78-percent tax increases over the next three years – but the city council rejected that as well as any plan that features tax hikes of more than 10 percent a year. Instead, the Scranton city council is suggesting additional contributions from nonprofits and commuter, sales and payroll taxes, among other ideas.

Part of the problem is that the city can’t get bank financing without first creating a viable Act 47 recovery plan that demonstrates exactly how it would repay the loans. (Act 47 – or the Financially Distressed Municipalities Act – enables the Pennsylvania Dept. of Community and Economic Development to declare certain municipalities financially distressed.) Scranton was first designated financially distressed back in January 1992.

But as bad as the situation is in this once-stalwart coal-manufacturing center of about 76,000 residents, the city has not yet sought bankruptcy protection from its creditors, as Stockton, California, did last week. Cash-strapped Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, tried to get bankruptcy protection recently, but the city council’s petition was thrown out by a federal bankruptcy judge.

RELATED: Another CA City Goes Bankrupt; More to Come?

“Harrisburg and Scranton have some similarities. Both cities have been scrambling to fix holes – but those holes are all across Pennsylvania,” said Neil A. Grover, an attorney and founder of Debt Watch Harrisburg, a taxpayers advocacy group. “There’s no system in place to address failing cities in this state and other places as well. Policies that were put in place a long time ago are coming home to roost, in Scranton and every place else.”

Grover says that Scranton is “free under the law to seek bankruptcy protection, but Harrisburg – a third-class city – is not. Only third-class cities in Pennsylvania are barred from seeking bankruptcy protection.” He adds, “I expect to see Scranton in bankruptcy before the month is out.”

“[Our city] has been through difficult times before and we have a history of making it through,” said Christina Hitchcock, assistant vice president of communications at the Scranton Chamber of Commerce, on Tuesday. “There are no easy solutions to Scranton’s fiscal situation.”

PICKED POCKETS

Last Friday the first slashed paychecks abruptly went out to city workers who had previously been making $19 to $26 an hour. The mayor said, “We’ll pay them as much as we’ve got, but that’s what we’ve got.” Scranton’s business administrator said the city would have only $5,000 left over after paying its workers minimum wage this week.

But on Tuesday, Scranton officials indicated the city will probably have more than $700,000 in its coffers and should be able, by the end of the week, to pay the full public worker payroll next week. That’s with a lot of hope and a bunch of crossed fingers. The city needs about $1.1 million to pay full salaries.

Public workers who received the reduced paychecks are owed their remaining pay and the city says it will, in due time, pay that back. But no one knows when that will be.

“My members cannot endure more pain,” said John Judge, president of the Scranton Firefighters Union, at a recent City Council meeting, referring to firefighter layoffs earlier in the year. “You want them to work for minimum wage… You want them thinking about all of the stresses this financial problem is going to put on their families while they’re trying to run into a burning building to put your fire out or to save your kid? No. you want them of good sound mind, just like you want the police officers and the DPW and clerical to concentrate on their job, because their numbers have been slashed as well.”

Roseann Novembrino, the city controller, said that the mayor gave everyone minimum wage because that was what he was able to give, according to Reuters.

“The city has no money,” said Robert McGoff of the Scranton city council at its June 26 meeting. “It’s living day by day... There is a hole in our budget that needs to be filled… [And it] needs to be filled with the cooperation of the lending community. Over the past couple of months I think our actions or inactions have made some of these institutions skeptical about whether we have the ability or the will to repay the debts we have.”