Not many cities can say they came out of the recession as well off as they went in. Bellevue, a suburb of Seattle, is one of the few.

Originally it was a small bedroom community designed for drivers commuting to the city. But in the last 25 years Bellevue’s leaders have planned a pedestrian-friendly downtown connected to public transportation and in the process created a booming street scene and high-tech magnet that’s become one of Seattle’s hottest spots. (CNN Money ranked Bellevue as its fourth-best place to live nationwide in 2010.)

RELATED: Housing Crisis Could End Suburbia As We Know It

That has people and developers pouring in—hundreds of new apartments and condominiums have gone up in Bellevue’s core, and restaurants, theaters, and night clubs have proliferated. The number of downtown Bellevue residents since 2000 has more than tripled to 10,000. A downtown transit center runs 1,400 buses a day to Seattle and further-out suburbs. Downtown’s job growth has soared 25 percent over the last decade as the area has attracted the headquarters of firms like Expedia, Eddie Bauer, and Intelius, plus 4,500 Microsoft jobs at the Bellevue branch. With light rail set to come in by 2023, Bellevue looks like a place to bet on for years to come.

Bellevue 1953

Not long ago, density, walkability, and access to public transit were more associated with cities than suburbs. But as more people flock to the cities, and many outer suburbs struggle, some suburbs have found a formula that’s helped them grow as fast as their urban siblings—create a downtown core that lets them combine the city’s culture, street life, and walkability with their own lower crime rates and good public services. City planning manager Paul Inghram thinks Bellevue’s advantage is blending urban amenities with “a lot of suburban characteristics like an excellent school system, great park system, and strong police and safety network.”

RELATED: The 10 Top Cities People Are Moving to in 2012

That approach plus the growing popularity of urban living has caused a surge in demand for residential and commercial space in suburban downtowns. New census data show a reversal in population growth, which for the first time in 2011grew twice as fast in cities and high-density suburbs. And in the last decade, the locus of the most desirable housing has flipped. In the late 1990s, the most expensive housing per square foot was in the high-end outer suburbs. A study released in May by the Brookings Institution found that today it’s in high-density, pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods in the cities and inner-ring suburbs.

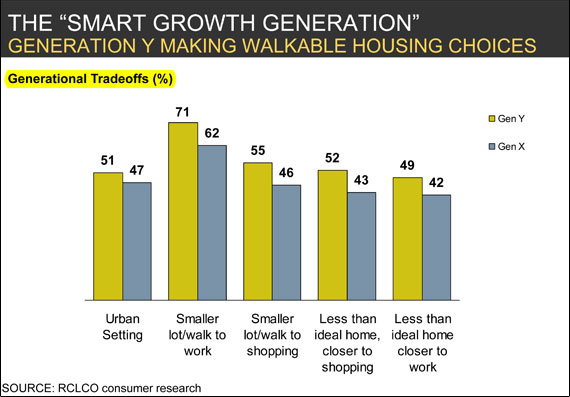

Driving the trend are two big demographic cohorts. Millennials—those born between the late seventies and early nineties—are coming of age, and those who can afford to live on their own are looking for places to rent that are near the action and that don’t require them to own cars, according to a February 2010 study by real estate consultancy RCLCO. At the same time, retiring boomers are selling their larger houses and looking for smaller living spaces nearer the city that are walkable and connected to transit.

Those evolving preferences also showed up in a 2011 National Association of Realtors survey—58 percent of Americans now say they prefer to live in a neighborhood where businesses are within walking distance rather than one with houses only that requires more driving. The tripling of gas prices since 2000 has also contributed to the trend.

As people ask for more urban amenities, developers are adapting. “Nobody’s building enclosed malls anymore,” says John Norquist of the Congress for the New Urbanism, which promotes sustainable neighborhood development. Replacing them are “lifestyle centers,” outdoor malls that are replicas of downtown shopping districts, like Carriage Crossing outside Memphis and Winter Park Village in a suburb of Orlando. Developments like that combine housing with shops and offices—so-called “mixed-use” zoning that planners used to shun, Norquist says. In a back-to-the-future twist, one developer building a suburban lifestyle center on Long Island is consulting old maps from the 1890s in drawing up his plans, says Norquist.

But creating suburban downtowns involves cutting through a thicket of challenges. One of Bellevue’s was an infrastructure that worked against walkability—huge “superblocks” 600 feet on a side, built with cars in mind, that took twice as long to walk as a normal city grid. Inghram says Bellevue leaders responded by cutting them up with pedestrian corridors and requiring that developers seeking building permits do the same. Now many of downtown’s main thoroughfares are car-free. Sixth Street, for example, is not actually a street for most of its length—it’s a main pedestrian walkway connecting city hall with the Bellevue Arts Museum and Bellevue Square, an upscale regional mall.

SMART PLANNING

Nationwide, state transportation agencies are starting to adapt when permitting new projects so that after-the-fact adaptations like those aren’t necessary. Norquist says many state planners are starting to move away from the traditional requirements that towns build bigger streets and blocks that move as many cars through as fast as possible. Today they’re allowing narrower streets and smaller blocks that are friendlier to pedestrian traffic.

Silver Spring, an inner-ring suburb of Washington D.C. can’t do much about its street layout—it has two high-volume roads cutting through its center. In the mid-eighties, its downtown went into decline after it lost several large retail stores to areas further out. Shuttered storefronts, low-rent thrift shops, and takeout restaurants took over its streets.

But starting in 1997, county planners launched an ambitious plan to attract developers to the area around its subway and bus terminals. Today the downtown is transformed, its public transportation hub surrounded by a dense collection of mid-rise apartment and condominium complexes (more than 1,600 new units have been added under the redevelopment plan), restaurants, the headquarters of Discovery Communications, and upscale retail stores like Whole Foods. Silver Spring’s population density increased 11 percent during the 2000s, the office vacancy rate is under 10 percent (down from 36 percent in 1996), and the area has attracted at least $1.2 billion in investment.

As more developers look to create transit-oriented suburban cores like Silver Spring and Bellevue, it’s an open question whether they’ll be able to build housing fast enough to keep up. RCLCO’s Shyam Kannan calculates that the demand for housing in high-density areas will exceed supply by 140 percent by 2014. And in his 2005 book Zoned Out, Jonathan Levine, University of Michigan professor of urban and regional planning, predicted that it will take a generation for the supply of housing in walkable neighborhoods to meet the demand.

If so, the only affordable place left to go could be back to where the sprawl started—the cul-de-sacs of outer suburbia.