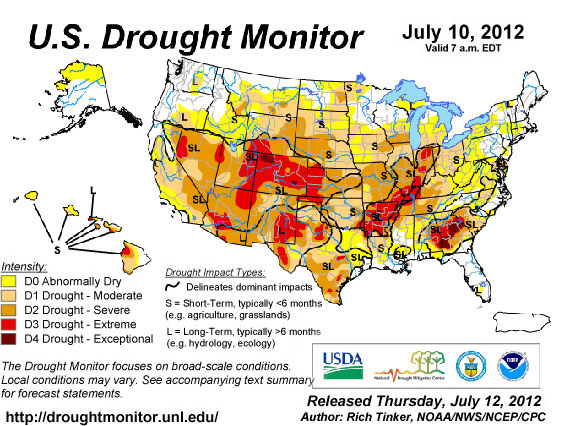

If you don’t have enough to worry about with the fiscal cliff, consider that Mother Nature, with an assist from fossil-fuel burning man, is readying her own knock-out punch for the economy. The drought in the Midwest just broke a 50 year old record, affecting corn, soy and other “core” crops. The drought follows the hottest 12 months since the National Weather Service began keeping records in 1895.

RELATED: Tornadoes, Hurricanes, Floods: Why You'll Pay, Too

We’ve been here before: the 1930s dust bowl, the rain-scarce late 1950s or the major droughts that hit the U.S. plains in 1980 and 1988. But if you look at the pattern of those 20th century droughts, you’ll notice that they occurred with depressing regularity about two decades apart. It has been more than 20 years since America’s last unwanted dry season.

In the 18 primary corn-growing states, 30 percent of the crop is now in poor or very poor condition, up from 22 percent the previous week, reports the National Drought Monitor. In addition, fully half of the nation’s pastures and ranges are in poor or very poor condition, up from 28 percent in mid-June.

The National Climatic Data Center reports that 2,202 heat records have been broken in the U.S. and another 787 tied in July—and the month isn’t over. Two months ago, during the warm spring weather, the U.S. Department of Agriculture predicted that corn production will increase nearly 20 percent to 14.8 billion bushels this year, largely because of higher yields from more acres being pressed into production. They estimated could fall as much as $1.50 to $5 a bushel. Now, they’re estimating $8 a barrel.

"Based on my conversations with producers, I would say 75 percent of the corn crop in the heart of the drought is beyond help," grains analyst Mike Zuzolo, president of Global Commodity Analytics & Consulting in Lafayette, Indiana told Reuters.

Get out your calculators. Food prices typically rise one percent for every 50 percent jump in corn prices, Richard Volpe, an economist for the Economic Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, told CNN. And of course, corn feeds cows, so beef prices will likely rise unless more are slaughtered because of the lack of grain.

Wheat production was also expected to jump 5 percent to 2.2 billion bushels, the highest since 2008. And exports were expected to surge about 10 percent to 1.15 billion bushels or nearly half of all domestic production.

So much for estimates.

The real issues are once again all about money and how this drought will affect local, state and federal budgets. Major economic disasters due to disruptive weather can add to deficits and rob consumers of their discretionary spending dollars. Last year’s drought in Texas caused more than $5 billion in damages to its livestock and agricultural industries.

The recently passed farm bill adds another dimension to the current drought. Currently the government subsidizes about 62 percent of the crop insurance premiums, and the policies typically guarantee 75 to 85 percent of a farmer’s revenues. Not a bad deal. The CBO estimates this program will cost more than $90 billion over the next decade, a $5 billion increase. But a new “shallow loss” program will force taxpayers to make payments to agricultural producers who suffer as little as a 10 percent loss of anticipated revenue. The bill also creates new entitlement programs, such as Agricultural Risk Coverage and Crop Insurance Supplemental Coverage Option.

The short-term effect of extreme weather events is food price spikes. When the price of basic food commodities like corn and wheat doubled in 2010, grocery bills soar.

RELATED: Extreme Weather Striking a Blow to Government Budgets

Still, most Americans barely feel the pain when commodity prices rise since they only account for 10 to 20 percent of the grocery story price of food. But the same can’t be said for poorer countries where food can consume half or more of household budgets.

“Our estimate is that prices will double by 2050,” said Nelson of IFPRI. “In the 21st century, we will be bumping up against the resource limits of the planet, both in land and water. As people get richer, diets improve.”

And climate change? That’s “a threat multiplier,” he said.