Here’s what passes for election-year debate over the fate of the American manufacturing sector in 2012.

Gov. Mitt Romney is accusing the president of crony capitalism for supporting emerging alternative energy companies that contributed to Obama’s campaign. The Romney campaign has isolated an ill-formed sentence in the president’s speech about the need to invest in infrastructure and education, and taken it out of context to attack him for believing that small business owners didn’t build their own businesses.

President Obama, meanwhile, is accusing the presumptive Republican nominee of moving jobs abroad to pad his personal fortune, even though Romney’s record on job creation while at Bain Capital is clearly mixed. He has also accused Romney of hiding that income in tax havens in Bermuda and the Cayman Islands.

Average Americans can be excused if they have no clue about one of the crucial choices they face this fall. What, if anything, should be done to help industry? Should the nation provide targeted support for goods producers or should it let the free-market rule?

The two candidates are offering a stark choice. For Obama and his economists, rebuilding U.S.-based manufacturing is a crucial building block for maintaining the long-term competitiveness of the U.S. economy and restoring jobs, income and wealth for the middle class. While manufacturing will never be the employer it once was, a thriving base of domestic goods producers will be required if American innovators are going to win out in global competition. In their view, researching and developing the next new thing – and all the jobs in design and marketing that ride on those coattails – increasingly depends on the ability to build the last new thing.

Romney and his economists take a different approach, one that says advancing the economy overall is the most important objective and capital should be put to its most productive use. If Americans have a competitive advantage in design, marketing and retailing of goods made elsewhere, capital will flow to those activities. It won’t depend on proximity to manufacturing, which can move off shore if it is more cheaply and productively made there.

Dig beneath the distorting advertising by both campaigns and one discovers they are offering approaches that fit well within ideological constructs that date back to the founding days of the republic. Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first Treasury Secretary, articulated a boldly interventionist strategy to promote manufacturing. Thomas Jefferson, the nation’s third chief executive, upheld a vision of limited government that said independent landholders in an overwhelmingly agricultural nation should be free to pursue their own dreams.

“Not only the wealth, but the independence and security of a Country appear to be materially connected with the prosperity of manufactures. Every nation, with a view to those great objects, ought to endeavor to possess within itself all the essentials of national supply. These comprise the means of Subsistence habitation clothing and defense.” – Alexander Hamilton

Romney and the modern Republican Party, which has lurched right in recent years, are clearly in that Jeffersonian tradition. They want less government, lower taxes, less regulation and fewer subsidies for special interests – although many in their party balk when producer groups in their districts such as alternative energy producers find their special subsidies on the chopping block.

While the Romney platform calls for helping businesses generally, including policies to support saving and investment, innovation and research, he is promising no special help for the manufacturing sector, even if its share of jobs and the overall economy continues to shrink as it has for most of the last four decades. Romney said the three Detroit automakers should have been allowed to go through a managed bankruptcy.

Although Romney has occasionally sounded tough on trade – he pledged to brand China a currency manipulator on day one and would remove an imbedded tax penalty that favors foreign carmakers – Romney is far more likely to take into the White House the view that is held by most Republican-oriented economists: that the sector may thrive through technology-driven productivity improvements, even though manufacturing jobs may continue to decline.

"Agriculture, manufactures, commerce, and navigation, the four pillars of our prosperity, are the most thriving when left most free to individual enterprise." – Thomas Jefferson

Any effort to forestall that outcome would merely distort the flow of capital to its most productive uses, they say. Romney’s role as chief executive of Bain Capital reflected that world view. If one of his investments succeeded by shifting the production of computer parts to China while another succeeded in opening up a chain of retail stores that sold those products back to the American people, the ample returns to private investors would justify both transactions, even if the net effect was to substitute lesser-paying retail jobs for better-paying manufacturing jobs.

The Obama administration says the government can and should attempt to arrest the erosion of manufacturing jobs rather than let the free market work its will. In a speech last March to a conference on American manufacturing, National Economic Council chairman Gene Sperling posited that the future health of the economy depended on a rebirth in manufacturing because the sector “punches above its weight.”

“When you take into account the outsized role that manufacturing plays in innovation – through R&D investment and patents; the tight linkage between innovation and manufacturing production; higher-wage jobs it produces; its importance for exports; the spillover benefits that manufacturing facilities have on firms and communities around them, and the deeper economic harm that comes from allowing our manufacturing production capacity to be hollowed out – it becomes clear that manufacturing is worthy of a special emphasis,” he said.

Earlier this month, the administration released a special report on “advanced manufacturing” that gave the broad outlines of the strategy it would like to pursue in a second term. The committee that authored the report, co-chaired by the Dow Chemical chief executive Andrew Liveris and Massachusetts Institute of Technology president Susan Hockfield, included the CEOs of Northrop Grumman, United Technologies, Honeywell, Allegheny Technologies, Stryker, Procter & Gamble, Ford, Intel, Caterpillar, Corning and Johnson & Johnson.

The group called for increased funding for R&D targeted at specific companies to help certain manufacturers modernize; the establishment of a network of regional manufacturing innovation institutes to help local goods makers; and increased investment in community colleges to steer talent, especially among returning veterans, into the manufacturing sector. They warned that failure to invest in manufacturing could jeopardize national security.

“Other countries have witnessed the unparalleled economic prosperity created by a manufacturing economy and appreciate the inherent value of manufacturing,” they wrote. “They are actively competing for manufacturing technologies and manufacturing production. The major economic competitors of the U.S. recognize the benefits from a vibrant manufacturing sector.”

There’s a model for some of their key recommendations. On the eve of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson signed a law creating the Agricultural Extension Service to insure that “the astounding variety of agricultural research funded by the federal government at leading universities – into crop varieties, animal care, soils, marketing strategies, water quality and a host of other subjects – doesn’t just sit in dusty reports (but) finds its way to the nation’s farmers,” to quote from an Indiana University description of the program.

It worked in ways that continue to confound predictions that the world’s burgeoning population will eventually outstrip farmers’ ability to produce enough food. A typical American farmer a half century ago could feed less than 30 people. Today, it’s more than 130. Are there more farmers today than there were then? Of course not. As wags love to point out, there are more employees at the Department of Agriculture than there are farmers in the U.S.

But if one counts the jobs at Monsanto, Dow Chemical, John Deere, Archers-Daniel-Midland, Cargill, hundreds of biotechnology companies focused on agricultural technologies, and the entire food additives, processing, packaging and marketing industries – not to mention the ag-oriented employees at commodities trading firms and exchanges – one gets a very different picture of “agricultural” employment.

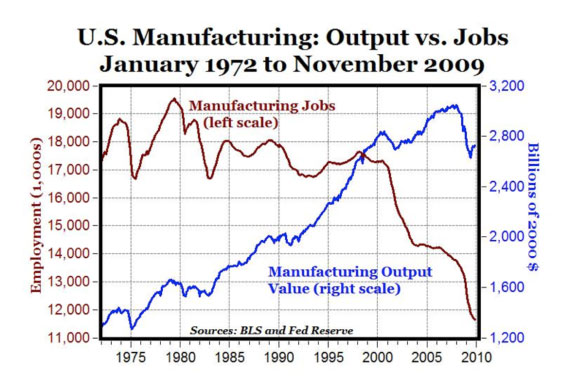

The same can be true for manufacturing, which has been undergoing a productivity and trade-driven transformation over the last four decades as the country transitioned to a service and information-based economy. Manufacturing’s share of total jobs and output in the economy fell from 27.5 percent of jobs and 21.3 percent of gross domestic product in 1979 to 13.8 percent of jobs and 12.2 percent of GDP at the end of 2011. But that underestimates its influence, since millions of jobs in law, accounting, business services, design and marketing depend on those manufacturing jobs and would go into decline when manufacturing moves offshore.

Unlike the earlier eras, when there was a consensus that government had a role to play in making an economic transformation work for most Americans, the decline in manufacturing has occurred in a policy environment that vacillated between modest support and outright hostility to the fate of workers and businesses in the sector. Not surprisingly, manufacturing’s decline has moved in similar fits and starts.

In 1984, after the reelection of Ronald Reagan and a devastating double-dip downturn that hit manufacturers especially hard, Democrat Walter Mondale ran for president on a platform that promised to forge an industrial policy that would help America’s manufacturers compete with their overseas rivals – in those days primarily from Japan and Germany. Castigated as seeking to have government “pick winners and losers,” he lost badly. By the end of a dozen years of Republican control of the White House, best summed up by President George H.W. Bush’s top economic adviser suggesting that it didn’t matter if the U.S. made computer chips or potato chips, the U.S. had lost nearly 2 million manufacturing jobs.

But during the two terms of President Bill Clinton, the U.S. reversed that trend. The “new” Democrats of that era came up with a different approach for aiding industry. Rather than providing targeted support to specific industries, industry policy advocates focused on broad strategies of improved job training and education that would help any business, manufacturers included. The Clinton administration also borrowed a page from the nation’s agricultural past by setting up a limited manufacturing extension service based in community colleges across the nation.

Did these policies help? It’s hard to say, but near the end of the 1990s, the nation had regained two-thirds of the manufacturing jobs lost during the recession that began the decade.

However, in the decade that led up to the Great Recession when George W. Bush was in the White House, the manufacturing sector went into a steep decline. With imports from China and other rapidly developing countries surging, the U.S. lost nearly 4 million jobs manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2008. During the first few months of Obama’s term, the nation lost another 2.4 million goods producing jobs.

The stimulus package adopted in the first few months of Obama’s term sought to address the stunning collapse. The administration used bank bailout money for emergency loans to the auto industry, which has since rebounded smartly. It targeted stimulus money to emerging energy technology companies, a few of which like Solyndra failed, but most of which are continuing to grow and add jobs.

From a macroeconomic viewpoint, the early results are promising. Since manufacturing jobs bottomed out in January of 2010, the sector has added 500,000 jobs through June 2012. Its share of the total economy has rebounded from an all time low of 11 percent in 2009 to 12.2 percent at the beginning of this year, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

“Most jobs will be in services,” Sperling said. “But manufacturing matters; manufacturing promotes the innovation and productivity that will keep America on the cutting edge, and that is why it will remain a key plant of the president’s agenda.”

Voters face a stark choice this fall between two vastly differing approaches when it comes to promoting the manufacturing sector. One can only hope the national media brings it to peoples’ attention since it’s clear from the campaign ads so far that the candidates have no intention of doing so.