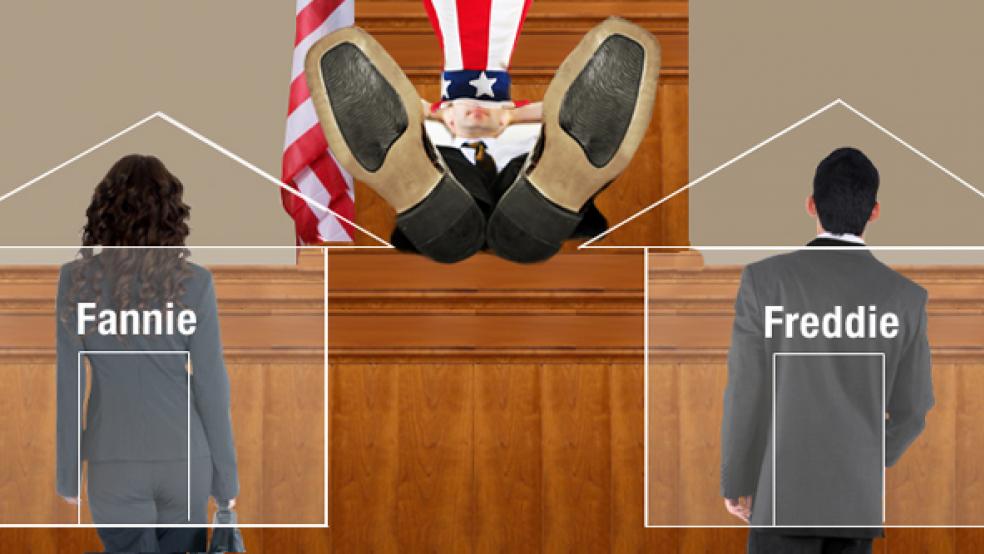

Congress has restarted its slog about the fate of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac – and at stake could be the future of your standard issue 30-year fixed-rate mortgage.

The two mortgage giants became wards of the state in 2008, when the housing bust brought them to their knees and a government conservatorship kept the entire industry afloat.

“Government Sponsored Enterprises” – the bureaucratic name for Fannie and Freddie Mac – currently account for 75 percent of all mortgages that get bundled into securities. Between them, Fannie and Freddie control a portfolio of 31 million mortgages worth a combined $5 trillion.

No public official disputes the need for the government to play a smaller role in the housing market. But the basic disagreement is whether the government should still guarantee the principal and interest on your mortgages. Supporters say the guarantees make financing affordable, while opponents say it inflates prices and puts taxpayers on the hook.

“The GSEs’ existence is essential to a housing finance market Americans want, not need,” said Jason Gold, a senior fellow at the Progressive Policy Institute. “Fixed rate loans are the foundation on which the entire system is built. The necessary ingredients for fixed loans on a widespread affordable basis are securitization and a government guarantee. There are only two significant places that combination runs through – GSEs and the Federal Housing Administration.”

The House Ways and Means Committee held a hearing Wednesday morning to look at foreign markets where no such guarantee exists, but rates of homeownership are higher and fixed rate mortgages are rare.

In his opening statement, committee chairman Jeb Hensarling (R-TX) claimed that Fannie and Freddie had not “propelled” the county to home ownership “nirvana,” saying that the guarantees had increased home prices and pushed millions of Americans into loans that were bound for foreclosure. Fixed rate mortgages are a “gold standard” for some, but a “rusty tin standard” for others, he said.

“The U.S. is practically alone in the modern industrialized world in having GSEs,” Hensarling said.

It’s the rare example of a Republican claiming the United States should be more like Europe. A higher share of people in Singapore, Italy, the United Kingdom and Canada own homes than in the United States, where the rate is 65 percent, according to the Census Bureau.

Hensarling has made no secret of his desire to end the guarantee. At an April hearing, Hensarling said his first goal is to “gradually reduce and eventually eliminate the government guarantee of Fannie and Freddie.”

According to committee staff, “much work remains” on finalizing “sustainable” reforms for housing finance legislation that would eventually come out of the House.

For the committee’s ninth hearing on housing reform, the key angle of attack was against the notion of government subsidies to encourage lending. The subsidies with their origins in the Great Depression created stable borrowing rates for homeowners, but Alex Pollock of the American Enterprise Institute, one of the members of the committee’s panel, told The Fiscal Times that the guarantees have only inflated prices and created new costs for taxpayers to bear.

“People are always deluded into thinking that you can get something for nothing by having the government guarantee,” said Pollock, a former banker and fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “In fact, everything has to be paid for.”

Pollock would prefer to force a reduction in the size of Fannie and Freddie’s portfolio over the course of seven years as the fate of the two firms get decided by Washington, so that the market would have time to adjust.

The two GSEs received $187 billion in taxpayer funding during the conservatorship. But the recent upswing in the housing market has enabled them to repay $95 billion more than expected this year, according to projections released last month by the Congressional Budget Office. The ratings agency Fitch said last month that improvements in the companies’ cash flow would “likely further reduce pressure on Congress to overhaul the U.S. housing finance system."

The real estate industry, not surprisingly, supports continuing the guarantees. In countries such as Canada, homeowners are stuck with variable interest rate mortgages that have balloon payments after five or seven years, meaning that they must be ready to refinance multiple times.

“We have a better system,” said Jamie Gregory, deputy chief lobbyist for the National Association of Realtors. “Granted, it went off the rail in the last decade.” He said that a European-style model would cause fewer Americans to buy homes, as lenders became less willing to accept the risks of a potential default on an unguaranteed mortgage and would respond by charging higher interest rates.

“Most stakeholders, builders, investors, lenders, financial institutions all believe that there has to be a government guarantee,” Gregory said. “The intellectual purists – the academics – have this idea that the market would function without it. I believe the home ownership rate would fall considerably without the government guarantees.”

President Obama proposed a framework of options for winding down Fannie and Freddie in 2011. The administration has since gotten behind a push to name Rep. Mel Watt (D-NC) as the head of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which oversees the two firms.

The Senate is reportedly putting together a bipartisan plan to replace Fannie and Freddie with a new entity to guarantee mortgages. Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN) and Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) are in the middle of crafting the bill and generating a coalition to support it, according to Reuters.

Corker’s office said it would be premature to comment on the “very fluid” process. But the goal is to ensure that taxpayers are not left to soak up any losses and that the replacement entity would have the cash reserves to be safe from downturns.

“Sen. Corker is involved in meaningful conversations with his colleagues to develop a sustainable and pragmatic housing finance model that would finally resolve the GSEs,” said Laura Herzog, a spokeswoman for Corker, “and he is hopeful that we can deal with this issue in the next few months.”