• Bank lending to businesses rose $3.9 billion in July and August • Corporate bond issuance could reach $100 billion this month • August inflation, excluding energy and food, was 0.9 percent |

Policy decisions by the Federal Reserve have always been driven by balancing the risk between inflation and recession. But never like this. On one side, the potential for an explosion in lending activity that could fuel inflation has never been so great, with the Fed having already pumped more than a trillion dollars in loanable funds into the banking system. On the other, if the economy were to slip back into a recession, the result could be a destructive round of Japanese-style deflation.

Such is the backdrop for tomorrow’s Fed policy meeting — and for the foreseeable future. As if that isn’t enough of a challenge, two factors are starting to complicate future policy decisions. The general tone of recent economic reports has taken a turn for the better, which raises the bar for any new action and will surely intensify the already hot debate within the Fed over the direction of policy. And even if policymakers decide on more stimulus, the real question is whether or not the added benefit to economic growth and jobs would outweigh the cost, especially in terms of possible pressure on inflation.

Since the Fed’s June meeting, when fears of new weakness or even recession seemed foremost in the minds of most Fed officials, that risk has begun to ebb. Payroll gains have been tepid but steady, and weekly jobless claims have retreated. Retail sales have perked up, exports have strengthened, and the industrial sector is still making gains. Plus, conditions in the capital markets continue to improve, as seen in recent stock market gains and in this month’s large issuance of corporate bonds, which some analysts estimate could reach $100 billion.

Fed watchers expect no new action Tuesday, but don’t rule it out for later. “The November meeting may provide a better backdrop for a change in policy,” says Michael Gapen at Barclays Capital, because the first estimate of third-quarter GDP will be released the week before and the minutes of the meeting will include an updated set of economic forecasts.”

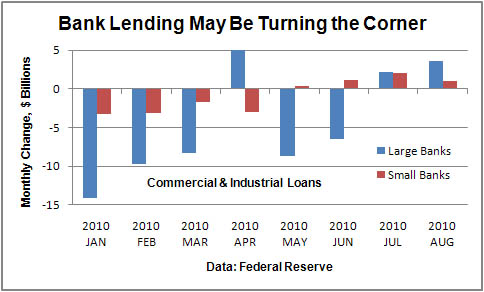

The nascent recovery in bank lending will be important in the Fed’s thinking. After all, that’s the real purpose of injecting all those funds into the banking system. Those funds had been sitting idle, but lending for commercial and industrial loans rose $1.3 billion in July and $2.6 billion in August, the first gains since the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in September 2008. The turnaround includes increased lending by both large and small banks. Consumer lending is a different story. Despite a Fed survey showing a 16-year high in banks’ willingness to make consumer loans, lending to households is still contracting, reflecting weak loan demand, as household deleveraging continues.

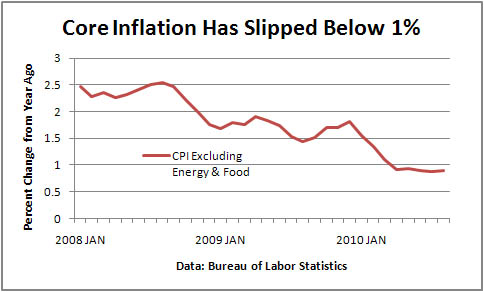

Recent comments by key Fed officials, including Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke, suggest the Fed is leaning toward further efforts to stimulate the economy. Recently retired Vice Chairman Donald Kohn, whose policy views have been closely aligned with those of Bernanke, told The New York Times that the Fed should take additional action if there were no prospects of progress in the job market or in getting inflation back up to about 2 percent to ensure against deflation. The Labor Deptartment pegged the August inflation rate at 1.1 percent, while the core rate, which the Fed watches closely because it excludes the ups and downs in energy and food prices, stood at only 0.9 percent.

Deflation, in which prices and wages spiral downward, would create an especially thorny problem for the Fed. Policymakers, and any economist for that matter, know it is real interest rates — or market rates minus what people expect inflation to be — that matter in the economy. If the Fed cuts its target rate amid a stable inflation rate, then the real rate will fall and stimulate the economy. The problem comes when the Fed cannot cut its target rate below zero, which is about where it is now. If inflation keeps falling, the real rate actually rises, with the perverse result of tightening policy in a weak economy.

Favorable conditions will not emerge if economic growth crawls along at the first-half clip of 2.6 percent in the coming year. Economists say growth will have to be 3 to 4 percent to achieve conditions such as those laid out by Kohn, and some say more Fed action is needed to assure that snappier pace. However, economists broadly agree that another round of purchases of government securities will have only a limited impact on further reducing borrowing rates for consumers and businesses.

Most crucially, housing and refinancing activity are not receiving the full impact of lower long-term rates. Many homeowners cannot refinance because they owe more than the value of their homes or because they are out of work. Fixed mortgage rates, which usually track 10-year Treasury yields, have fallen to a record low 4.5 percent, but relative to the 2.5 percent yield on Treasurys, the spread is still above the historical average at a time when it should be well below. “Pushing Treasury yields lower, when 10-year yields are already near 2.5 percent and the mortgage refi pipeline is clogged, doesn’t really accomplish much,” notes Morgan Stanley economist David Greenlaw.

The ineffectiveness of the Fed in spurring overall demand, especially by consumers, has led to several unconventional policy suggestions. One, from former Fed Vice-Chairman Alan Blinder, involves Fed purchases of private-sector securities, such as corporate bonds. That would lower borrowing rates but also create touchy questions about favoring certain companies or industries. Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman has suggested that the Fed announce it is seeking a higher inflation rate, perhaps 3 to 4 percent, instead of 2 percent. The intent would be to avoid deflation and push down real interest rates, but Bernanke has publicly rejected that notion as contrary to the Fed’s commitment to stable inflation.

In the past two years a mixture of innovative and unconventional policies succeeded in keeping the economy out of Great Depression II. In the coming year, the Fed may need even more innovation and unorthodoxy to nurse the economy back to health.