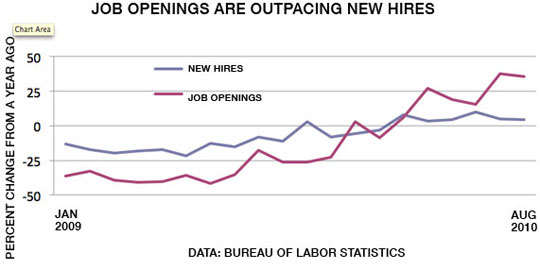

• Job openings are up 34 percent, but hiring only 4 percent. |

What can policymakers do about stubbornly high unemployment? Econ 101 says that in recessions, monetary and fiscal policies intended to stimulate the economy will boost demand for the things companies produce, increasing the need for more workers. But sometimes it's more complicated than that. What if people are unemployed because businesses can't find workers with suitable skills, and the available workers can't fill employers' needs? In that case, policies aimed at spurring demand for goods and services would not be very effective. They might even create shortages that could kindle inflation.

There's growing debate over how much of today's 9.6 percent jobless rate is cyclical and how much is structural. Cyclical unemployment simply reflects the ups and downs in overall demand during recessions and recoveries. Structural unemployment is a thornier, longer-term problem. It's caused by a shift in the labor market's structure that creates mismatches between the types of job openings and the skills of available workers. Structural unemployment is less amenable to short-term government stimulus measures. It demands education and retraining so workers can adapt to new sources of growth and employment. That's especially true given the ongoing shift to a knowledge-based economy, in which ideas and innovation are the keys to creating value.

Most economists believe both factors are at work now, but the question, especially for policymakers, is which one is more important. The debate can run along political lines. Conservatives are increasingly embracing the structural argument, which would imply little bang for more taxpayer bucks. Even some policymakers at the Federal Reserve believe that additional monetary stimulus would be ineffective or even counterproductive if it raises the risk of future inflation. Liberals, who favor more government action to stem joblessness, tend to make the cyclical case. Economist and Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman has gone so far to say structural unemployment is a "fake problem."

Real or not, the main evidence for the structural argument is the recent disconnect between job openings and hiring. So far this year the number of openings in the private sector has increased by 34 percent, while actual hiring has risen by less than 4 percent, based on Labor Department data. The numbers imply that one additional person has been hired for every five new openings, which suggests something other than a weak economy is keeping joblessness high. Economists also note that the longstanding relationship between job openings and the unemployment rate, known as the Beveridge Curve, has broken down recently. Typically, as job openings rise, the unemployment rate falls, but despite this year's jump in openings, the jobless rate hasn't budged.

The debate has split policymakers at the Federal Reserve. The Fed is widely expected to begin a series of purchases of Treasury securities after its early November meeting, aimed at lowering long-term interest rates and boosting demand. Philadelphia Fed President Charles Plosser and the Minneapolis Fed's Narayana Kocherlakota have said such purchases will be ineffective in lowering unemployment, given skill mismatches. "It's hard to see how the Fed can do much to cure this problem," Kocherlakota said in a speech in August.

However, most Fed officials downplay the role of structural unemployment, based on minutes from the Fed's September 21 meeting. Many participants said structural factors alone couldn't explain the high level of unemployment. Any broad mismatches of skills would show up as labor shortages and upward pressure on wages in certain industries and geographic regions, which are not apparent. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke weighed in on the issue in a speech Friday. "My assessment is that the bulk of the increase in unemployment since the recession began is attributable to the sharp contraction in economic activity that occurred in the wake of the financial crisis and the continuing shortfall in aggregate demand since then, rather than to structural factors," he said.

|

The evidence supporting Bernanke is strong and centers on broadly depressed levels of demand across the economy. It's not just housing. Car sales are nearly 30 percent below their pre-recession high, and many areas of consumer spending, ranging from clothing and restaurants to public transportation and financial services, remain depressed. Overall demand by consumers, businesses, governments and overseas buyers is still 2 percent below its level prior to the recession. This is the only time since the 1930s in which demand has failed to surpass its pre-recession peak in the first year of economic recovery.

One problem is that prolonged unemployment, for whatever reason, tends to create structural unemployment, and record long-term joblessness has been a key feature of this recovery. In the second quarter, 30.1 percent of the 14.6 million jobless workers had been unemployed for a year or more, up sharply from 14.2 percent in the same quarter last year and from 9.8 percent in 2008, according to a Labor Department report.

Long-term unemployed workers tend to lose skills and contacts, get shut out of declining industries or lose opportunities to younger and cheaper workers. The recession also created another problem: Many people cannot sell their homes in order to move to where they can find a job. People who have been unemployed for a month or less have a better than 30 percent probability of finding work in the following month, based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau. After being unemployed for six months, the chance of landing a job in the next month plummets to less than 10 percent.

The debate over the causes of high and seemingly intractable unemployment — and what to do about it — won't go away anytime soon. Even if all the new openings this year were filled by new hires the jobless rate would still be more than 9 percent. The ball is clearly in the policymakers' court, but with interest rates already scraping bottom and big deficits limiting fiscal stimulus, there may be no quick or easy solution.