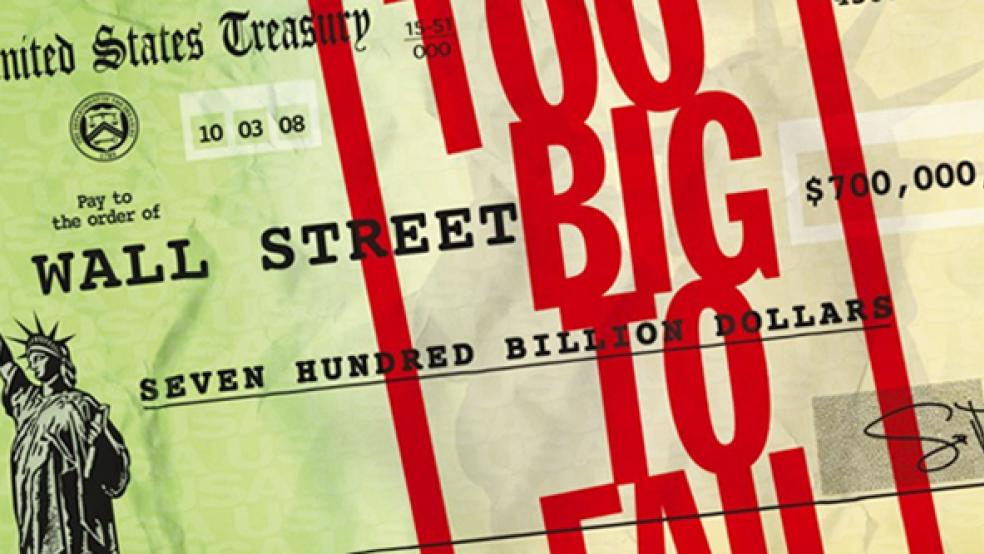

If newspaper reporters write the first draft of history, newspaper reporters with big, fat book contracts write the second. But history never really goes mass market until Hollywood gets hold of it. HBO Film’s “Too Big to Fail,” which premiers tonight, takes the financial meltdown of 2008 to the final stage of that evolution and artfully translates New York Times reporter Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 600-page tome into prime time. How much insight survived the translation is another question.

To squeeze the near death of capitalism into a single evening’s viewing, director Curtis Hanson and screenwriter Peter Gould focused on then Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. Leading financial and historical figures pop up continuously in the film, all played by actors; subtitles help you keep them straight. The film begins in May of 2008 as Lehman Brothers is unraveling and Paulson’s team is tying to persuade some other bank to buy Lehman before it goes under. For the next 105 minutes, Paulson, his aides, his allies, and his enemies (the bank CEOs) race around delivering boardroom ultimatums, shouting profanities into cell phones, and improvising strategies to save the world’s financial system. It’s about as crowd pleasing as any film can be in which all the crashes and implosions are metaphorical.

Naturally, a certain amount of financial nuance gets painted over in this kind of film, and events and characters get mushed together. Ben Bernanke, played by Paul Giamatti with a Zen-like, soft-spoken authority that the real character has rarely shown, functions mainly as an advisor to the Paulson team. In a historical sin of omission, Hanson and Gould never mention the alphabet soup of creative emergency loan programs that Bernanke’s Federal Reserve created on the fly—like the Term Asset-Backed Securities Lending Facility and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility—that arguably did more than anything emerging from Treasury to stabilize the markets.

... The characters trying to save their companies and

capitalism as we know it were the same people

responsible for nearly wrecking it.

There are also historical sins of commission. In one that caught my attention, Lehman Brothers’ attractive CFO Erin Callan, played by Amy Carlson, casually helps CEO Dick Fuld (James Woods) get into cuff links before a meeting. The offhand nature of the gesture implies that she has helped Fuld get dressed many times before. The suggestion of a back story between the two adds dimension to their characters and may be good movie making—but Sorkin’s book mentions no such familiarity between the two. Sorkin does report unsubstantiated rumors that Callan was involved with another Lehman executive, not Fuld. But hey, that’s show biz.

In a way, it’s unfair to criticize the film for infidelity to Sorkin’s book. Fidelity isn’t the point; drama is. And on that measure, the film does a good job. It keeps up a breakneck pace of plot development and maintains a sense of urgency that would do Law and Order proud. I had no trouble following the story (although because of my job, I may not be the best stand-in for a general viewing public).

What did get lost in the Hollywood translation is any sense of how the crisis came to be. The only real attempt at an explanation comes in a scene more than halfway through the film in which Paulson and other members of his team brief public affairs director Michele Davis (Cynthia Nixon) on the causes of the crisis. It was the first inkling a novice viewer would get that the characters trying to save their companies and capitalism as we know it were the same people responsible for nearly wrecking it.

A greater sense of how the world got to 2008 might have colored the film’s depiction of its main characters. You can’t fault Hanson and Gould for wanting to have heroes or for finding them in Paulson and his conscientious, underslept team, the Yoda-like Bernanke, and the smart preppy Geithner (Billy Crudup). Never mind that these characters, too, did their part to create the crisis. Paulson as CEO of Goldman Sachs helped tear down regulations that might have prevented reckless excesses in derivatives. And Bernanke, as Fed chairman, failed to enforce existing bank regulations that could have contained the mortgage crisis.

It didn’t stop the recession, didn’t reverse

unemployment, didn’t convince banks to lend, didn’t halt

the stock market slide, and only extended the power of

too-big-to-fail banks.

Films need villains, too, and in a script featuring some of the most hated contemporary figures in America, it seems odd that there are none. From Gould’s script, it would appear, for example, that Dick Fuld’s main mistake at Lehman was to believe naively that real estate would bounce back eventually. Little is made of Lehman’s 30 to 1 leverage or its use of shady accounting to hide the fact from regulators. The point is not that real estate won’t bounce back eventually. It’s that no one with 30-to-1 leverage will be around to see it. Goldman Sachs’ Lloyd Blankfein (Evan Handler) similarly just seems like another CEO bent on saving his company; there’s no mention of the fact that the company spent the years leading up to the crisis pushing toxic securities on unsuspecting customers. Maybe that will get covered in the prequel.

In an interview with CBS MoneyWatch’s Jill Schlesinger, Sorkin said that the toughest part of writing the book was that “everyone knows how it ends.” Well, in a sense. The book and the film end at the same spot, with Paulson’s team persuading the big banks to take $125 billion in TARP money. It’s a political success for the film’s heroes, but it wasn’t actually the end of anything. It didn’t stop the recession, didn’t reverse unemployment, didn’t convince banks to lend, didn’t halt the stock market slide, and only extended the power of too-big-to-fail banks, leaving the global economy more vulnerable than ever.

Sorkin also told CBS MoneyWatch that Wall Street’s culture and sense of entitlement have returned to their pre-crisis levels. Most of the bankers who held their jobs at the end of the film still have the same jobs, doing essentially the same things, despite the havoc they wreaked on the global economy and their own shareholders. Whatever may have been the toughest part of writing Too Big to Fail, the toughest part of watching it was knowing that for all the efforts of action-figure leaders like Paulson, nothing on Wall Street has changed. Yes, sad to say, we know how this action/adventure caper turned out. The bad guys won.

Related Links:

They Shoulda Known! Financial Crisis Was Avoidable (TFT)

Missing the Teachable Moments from the Financial Crisis (TFT)

How Wall Street's Inside Job Brought Down the Economy (TFT)