|

The fear of another recession, heightened by the jarring events in Washington and on Wall Street, raises a crucial question: Can consumers save the day? As many analysts had predicted, the temporary factors that had depressed spending in the first half—high gas prices, weak auto sales, stagnant job growth—are beginning to reverse. However, strong new headwinds, including the drop in stock prices and the plunge in confidence, have taken their place. How households respond to this latest test of their resilience is now the central issue in the outlook for the economy. Households, which account for 70 percent of GDP, will be the deciding factor between continued modest growth and a double dip.

Households are caught in the middle of a competency crisis. Economists at J.P. Morgan believe the stock market selloff reflects the combination of a stubbornly weak economy and growing concerns about the competency of policymaking institutions to do anything about it. “I think one of the issues for the markets right now is whether or not policymakers have the effective tools, whether they are actually competent enough, to deal with the issues at hand,” says J.P. Morgan economist Bruce Kasman. Policy doubts are fueling Wall Street caution, which threatens to spill over to spending decisions. The bank cut its forecast for economic growth on Aug. 19 to only 1 percent in the fourth quarter and to a mere 0.5 in the first quarter of 2012.

Prior to the policy and market turmoil in early August, the signs looked encouraging. Gas prices had begun their seasonal decline, a promising sign for the buying power of household incomes, especially with oil prices down more than 25 percent since May. Auto sales in July rebounded to a 12.2 million annual rate, up from the weak May and June readings that were depressed by Japanese-related shortages. That gain helped to lift July retail sales, which rose by a stronger-than-expected 0.5 percent. Plus, private-sector payrolls rebounded in July with a solid 154,000 gain, bolstering prospects for household incomes, and the trend in weekly unemployment filings continued to slide downward.

However, all this has quickly become old news. The plunge in stock prices, which began in late July, will almost certainly depress spending further. From July 22 through Aug. 19 the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index has dropped about 15 percent, wiping out roughly $3 trillion in household wealth. In early August the Reuters/University of Michigan index of consumer sentiment sank nearly 14 percent, to 54.9, a level below the worst reading during the financial crisis and the lowest since 1980. Despite the encouraging July data, attention is now on upcoming August reports, especially those from the labor markets, retailers, and auto dealers, for signs of any new pullback in consumer and business behavior.

Before the market meltdown, the upturn in July retail sales looked like a watershed report. The broad 0.5 percent gain went far beyond a rebound in auto sales, and Washington statisticians revised sales in both May and June a tad higher, putting sales on a stronger trajectory. Economists said the gain put overall consumer spending in July on a path to grow at an annual rate of nearly 2 percent in the third quarter, well above the weak second-quarter showing and close to the average quarterly gain over the past two years. Now, that path looks a lot more doubtful. In the face of big wealth losses, households tend to compensate by saving more of their income and spending less.

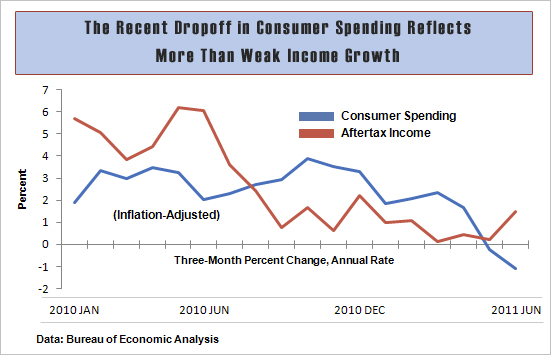

The pattern of consumer spending in the first half of the year raises a yellow flag for the second half. Earlier this year, households showed a clear lack of resilience to negative shocks, including surging energy prices, a renewed rise in unemployment, the Japanese disasters, and more worries about Europe. Consumer sentiment began falling as far back as March. Household incomes were not the major problem. Although squeezed by $4-per-gallon gas, inflation-adjusted income continued to rise slowly through the second quarter, but spending fell broadly for three months in a row in April, May, and June, something that rarely happens outside of a recession.

Perhaps sensing the economy’s vulnerability to the stock market’s plunge, the Federal Reserve jumped back into policy action on Aug. 9, saying it will not raise interest rates for two years, barring much stronger economic growth. Subsequent comments by Minneapolis Fed President Narayana Kocherlakota, who along with two other policymakers voted against that action, suggest that Wall Street’s plunge influenced the Fed’s decision. The central bank also appeared to leave the door open for additional actions. At the Fed’s annual policy symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, on Aug. 26-28, all eyes will be on Chairman Ben Bernanke, looking for any new policy guidance.Still, economists believe that any additional Fed actions will have only limited effectiveness, perhaps lowering long-term interest rates by a few hundredths of a percentage point. That will help those consumers who are showing a new desire and ability to borrow. Many households have cut their debt loads to manageable levels that allow more borrowing, as seen in the recent upturn in non-mortgage consumer loans. However, rock-bottom rates offer little benefit where help is needed most—in housing.

The average 30-year fixed mortgage rate fell to 4.15 percent in early August, according to Freddie Mac, a level not seen since the 1950s. That’s a benefit for homeowners who can qualify for a refinancing, which has risen sharply, but homes sales have declined steadily this year, dropping a further 3.5 percent in July. Banks’ mortgage lending standards remain very tight, keeping a lid on demand and prices. These conditions limit the full transmission of lower rates to household balance sheets, says Barclays Capital economist Michael Gapen, given that the home is most consumers’ biggest asset.

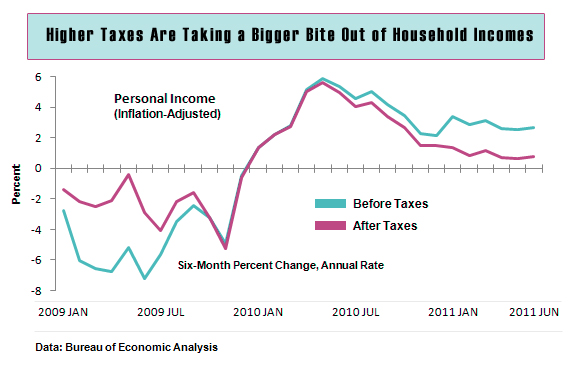

Even as monetary policy lacks effectiveness, fiscal policy is already contracting and its drag on growth is set to increase in 2012. Tax policy is cutting into income growth, especially as cash-poor state and local governments raise taxes. In the first six months of 2011, inflation-adjusted household income before taxes rose at a 2.7 percent annual rate. After taxes it increased only 0.8 percent. More important, about $350 billion in current stimulus programs, including the 2011 payroll tax cut and emergency unemployment benefits, are scheduled to expire by the end of the year, enough to subtract about 1.8 percentage points from GDP growth in 2012, according to estimates by economists at J.P. Morgan.

The bottom line is that the markets will not settle down without better news on the U.S. and global economies, especially on the European debt crisis. Barring that, the growing danger is a vicious cycle between Wall Street and consumer spending that could threaten this fragile economic recovery even as policymakers appear strapped for effective solutions.