|

So far, Europe’s chief problem has been its sovereign debt crisis, which Italy threatens to make evermore explosive. Now the Continent faces a new problem that will greatly complicate the first one. Economists increasingly believe the 17-nation Eurozone is sliding into a recession that will only magnify the troubles of heavily indebted governments and heighten the risk that the U.S. and global economies may be dragged down with it.

Europe now faces a dangerous dilemma. A recession means that budget-deficit projections in the debt- strapped nations, which are currently based on continued growth, are far too optimistic. New shortfalls will create the need for even more austerity measures in order to meet the fiscal targets required in some cases for outside financial support. European policymakers must now choose between fiscal reform and economic growth. The problem is that any lasting solution to the sovereign debt crisis—and the reduced risk for global financial contagion—needs both reform and growth.

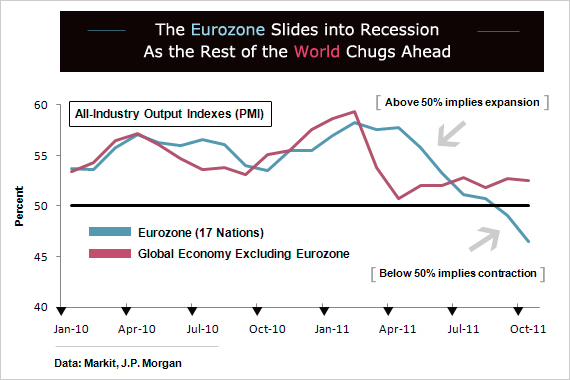

Eurozone weakness intensified at the beginning of the fourth quarter, reflecting the combination of heightened financial stress, budget tightening, and lackluster global growth. Markit’s Purchasing Managers’ survey, a composite output index across the region that closely tracks GDP growth, has fallen the most since just after the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, hitting a 28-month low in October. “It’s just breathtaking how fast these surveys are going down,” says J.P. Morgan global economist David Hensley. European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi said candidly on Nov. 3 that Europe was heading toward a “mild recession.”

Weaker European demand is already being felt in U.S. exports, and China’s trade data show a sharp drop in shipments to Europe, which is the mainland’s biggest export market. However, the far greater risk to the U.S. and global economies is through the financial markets. UBS estimates that European demand accounts for about 41 percent of the revenues of the companies in the S&P 500 stock index. More important, given the global interconnection in the financial markets, the intensification of the credit strains in Europe could ultimately travel to the U.S. and elsewhere. “In our view, an Italian default would be a Lehman-like event for the global economy,” Wells Fargo analysts said in a research note.

Even the growing fear of such a shock is already starting to show up in tighter global credit conditions. A composite of the fourth-quarter surveys of senior loan officers in the U.S., Eurozone, Japan, and Britain show that banks tightened their lending standards for the first time in two years. Also, a survey by the Institute of International Finance shows that emerging-market banks face increasing difficulty in accessing funds. Credit has been the jet fuel for emerging-market growth, which has been the main engine of global growth. “If something were to cut off the credit spigot, you could have a pretty abrupt shift in growth rates across the emerging world,” says J.P. Morgan’s Hensley.

A Eurozone recession will only intensify the credit strains. The Italian government’s borrowing cost for 10-year notes has soared to around 7 percent, compared with 1.7 percent for Germany and 2 percent for the U.S. Borrowing rates for Spain are 5.7 percent. “The surge in Italian and Spanish yields threatens to become explosive, particularly in the face of the impending fiscal austerity,” says Barclays Capital economist Julian Callow. Even for France, where rates have risen to 3.2 percent, the spread with Germany has widened to nearly a 20-year high, about three times greater than a year ago. As a percent of GDP, French banks are the most exposed to Italy’s debt, according to the Bank for International Settlements.

Recession is a particular problem for Italy, whose finances are especially vulnerable to high borrowing rates. Italy’s debt is some 2 trillion euros ($2.7 billion), which is about 23 percent of all Eurozone sovereign debt and five times the IOUs of Greece. Economists at Barclays Capital believe, with Italy’s debt at 120 percent of GDP, Italy’s finances will spiral out of control if it has to borrow at rates higher than 5.5 percent. Higher borrowing costs raise the risk of default, which pushes up rates even higher, and so on. Against that backdrop, Italy must come up with more than 200 billion euros in principle and interest payments between now and April.

Italy’s fiscal problems run deep. Since the start of Europe’s single-currency in 1999, Italy has grown only 0.6 percent annually, but it needs to grow at more than twice that pace to lower its ratio of debt to GDP, say analysts at J.P. Morgan. If Morgan’s forecast for a 1.5 percent contraction in Italy’s GDP in 2012 holds up, Italy will be hard-pressed to convince the financial markets that its finances are sustainable. The recently passed package of structural reforms, including state-owned asset sales, privatization of public services, and a higher retirement age won’t change that. The reform package omits crucial and painful labor-market reforms that union opposition has stymied.

For Italy and the other heavily indebted governments, recession will make new austerity measures all the more difficult to implement. In the absence of additional austerity, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, and Belgium will need to address much wider deficits than their governments now project, says Europe economist Nicola Mai at J.P. Morgan. As the social unrest in Greece illustrates, reaction to deep structural reforms can negatively affect political, financial, and economic stability.

The Eurozone’s battle to balance fiscal reform with economic growth, while holding its financial system together, highlights the growing threat to U.S. and global economic growth. International Monetary Fund chief Christine Lagarde told a financial forum in Beijing on Nov. 9 that the failure to clear away the clouds hanging over the world economy, especially those over the Eurozone and the U.S., could usher in a global “lost decade of low growth and high unemployment.” A Eurozone recession only raises that risk.