Tuesday’s failure to recall Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker is being widely interpreted as a political defeat for organized labor. After Walker and a Republican-controlled legislature stripped most public employee unions of bargaining rights, unions saw their very existence at stake and pulled out all the stops to punish Walker and overturn the law.

Wisconsin seemed like favorable ground for such a political fight. The state has a long tradition of progressive politics and union density is higher than in most other states. About 13.3 percent of all workers in Wisconsin belong to a union versus 11.8 percent nationwide.

However, the unions suffered from two problems that handicapped their efforts.

First, unions in general have endured a long decline in power, influence, and popularity. In the 1950s, more than a third of all workers belonged to a union. As recently as the 1970s, a quarter of all workers did. Strikes were common and those in a strategic industry such as railroads or steel could virtually shut down a significant portion of the entire U.S. economy.

George Meany, president of the AFL-CIO from 1955 to 1979, was widely considered to be one of the most powerful men in America. I had to check to see who the current president is. (It’s Richard Trumka, who has held the job since 2009.) The number of strikes has fallen from 200-400 per year in the 1970s to just 19 last year. It’s hard to remember the last one of any significance.

RELATED: How California Unions Hijacked the Golden State

There are many reasons for the decline of labor unions, but the leading one is simply that those industries most amenable to unionization and where unionization was highest have been among those that have declined most sharply in recent years. Those on the upswing tend not to have many union members. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, between 2003 and 2008, unions lost 138,653 members in auto manufacturing but gained just 4,736 in computer systems design.

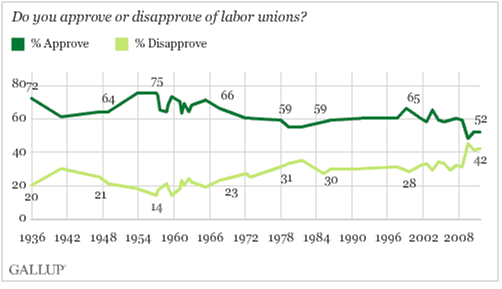

Concomitant with the decline of union influence has been a sharp decline in union popularity. According to Gallup, union approval has fallen from 75 percent in the 1950s to 52 percent; disapproval has risen from 14 percent to 42 percent. An Economist/YouGovpoll out this week found only 38 percent support for unions and 32 percent disapproval.

A detailed study by Pew last year found that Americans tend to view unions as having a negative effect on productivity, job creation, and the ability of American firms to compete globally.

The second big problem for unions is the changing composition of unionization. At one time, unions were largely based in the private sector; today, a majority of all union members work in government.

There is a fundamental difference between private sector workers and those in the public sector. If a private worker gains increased pay and benefits it does not come at the expense of other workers. But if public sector workers increase their pay and benefits it increases the taxes paid by private sector workers.

Moreover, the nature of what public sector workers do is fundamentally different from what private sector workers do. There is no profit to share and society depends on public sector workers to do their jobs without interruption. In return, public sector workers generally are accorded job security and rich benefits to a much greater extent than private workers.

Even Franklin D. Roosevelt, probably our most pro-union president, recognized the difference and strongly opposed strikes by government workers. As he wrote in a 1937 letter:

All Government employees should realize that the process of collective bargaining, as usually understood, cannot be transplanted into the public service. It has its distinct and insurmountable limitations when applied to public personnel management. The very nature and purposes of Government make it impossible for administrative officials to represent fully or to bind the employer in mutual discussions with Government employee organizations. The employer is the whole people, who speak by means of laws enacted by their representatives in Congress. Accordingly, administrative officials and employees alike are governed and guided, and in many instances restricted, by laws which establish policies, procedures, or rules in personnel matters.

Particularly, I want to emphasize my conviction that militant tactics have no place in the functions of any organization of Government employees. Upon employees in the Federal service rests the obligation to serve the whole people, whose interests and welfare require orderliness and continuity in the conduct of Government activities. This obligation is paramount. Since their own services have to do with the functioning of the Government, a strike of public employees manifests nothing less than an intent on their part to prevent or obstruct the operations of Government until their demands are satisfied. Such action, looking toward the paralysis of Government by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.

Another problem is that public sector workers have, in a sense, an unfair advantage in labor negotiations because they can not only strike but also bring political pressure – votes and contributions – to bear. Public employee unions are the most powerful political force in most major cities, making it very difficult for politicians to act in the public interest.

Also, the limited time that politicians are in office encourages them to make penny-wise/pound-foolish deals with the unions. For example, trading pay increases today for higher pension benefits in the future when they are out of office and don’t have to worry about paying for them.

This is possible because governments tend to operate on a cash basis, with future costs largely hidden from the view of voters. Now the chickens have come home to roost and the bad pension deals of past administrations must be paid and current taxpayers are outraged. Moreover, it’s not hard to find examples of workers who abused the pension system by, for example, doing a lot of overtime work their last couple of years on the job and sometimes retiring with pensions higher than their base pay as a consequence.

As states and localities struggle to reduce public employee pension costs, unions’ resistance is likely to make them even more unpopular than they already are. State and local governments were foolish not to adopt defined contribution pension plans in the 1980s, as the federal government did. They are now virtually the only entities still offering traditional defined benefit pension plans.

One should resist reading too much into the Wisconsin results – exit polls suggest that antipathy to recall elections themselves was the decisive factor. But certainly the unpopularity of unions in general and public employee unions in particular was a powerful subtext.