The January 1 vote in favor of H.R. 8, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, may have marked a profound change in congressional governance. That is because the legislation, which embodied measures to avoid the so-called fiscal cliff, passed with a majority of Republicans in opposition. This marks the first major breech of the “Hastert Rule” since Republicans gained control of the House in the 1994 elections. It suggests the possibility of a new governing coalition in the House that could have profound political implications.

During the long era of virtually uninterrupted Democratic control of the House from the 1930s to the 1990s – punctuated only by two brief periods of Republican control from 1946 to 1948 and from 1952 to 1954 – it was in fact largely controlled by a coalition of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats most of the time.

The “conservative coalition” first arose in 1937 after President Franklin D. Roosevelt put forward his highly controversial court packing scheme to increase the size of the Supreme Court, which had ruled a number of his initiatives unconstitutional. Adding more seats to the court would have allowed him to add additional liberal members.

Southern Democrats were especially critical of the court packing scheme because they knew that the greatest threat to segregation in the South, especially in the public schools, was from a Supreme Court ruling. They were right to be concerned; in 1954 the court did in fact rule that enforced racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

In those days, the Democratic Party’s base was in the South, as it had been since the end of Reconstruction. After federal troops were withdrawn and federal protection for the voting rights of African Americans effectively ended, the Republican Party disintegrated in that region for the next 100 years.

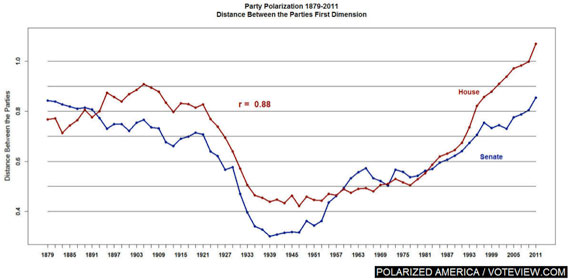

Although loyal members of the Democratic Party, most white Southerners tended to be very conservative, philosophically, especially on economics and foreign policy. On those issues they had much more in common with Republicans than Northern Democrats such as FDR. The result was development of the conservative coalition of Republicans and Southern Democrats that controlled both the House and Senate for more than a generation through 1974. This fact is illustrated in the chart from political scientist Keith Poole, which shows that partisanship in Congress fell sharply from its historical level.

The conservative coalition began to break apart in the 1960s as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 isolated Southern Democrats from most Republicans, who supported those measures both for philosophical and partisan reasons. Until 1964, about a third of African Americans voted Republican and Republicans thought that increasing their ability to vote would help them, electorally. Unfortunately, one of the few Republicans to vote against the Civil Rights Act was the 1964 Republican presidential nominee, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, who believed the legislation was unconstitutional, which reduced the Republican share of the black vote to 10 percent.

The big Democratic victory in the 1974 elections, in the wake of Watergate, effectively ended Democratic domination of the South. Southerners were purged from committee chairmanships in the House and many conservatives in the South felt they no longer had any practical reason to remain in the Democratic Party.

However, even in the 1980s there were still enough conservative Democrats left in Congress to give Ronald Reagan important legislative victories. But as time went by, most of those conservative Democrats either retired and were replaced by Republicans or switched parties. Now the Republican Party dominates the South as thoroughly as Democrats did during the era of the “Solid South.”

Once in control of both houses of Congress, Republicans rejected coalition politics. Former House Speaker Dennis Hastert operated on an informal rule which said that bills without support from a majority of the Republican Conference would not be permitted to have a floor vote. This rule was enforced by the House Rules Committee, which the Speaker largely controls.

The so-called Hastert rule polarized the House and led to legislative gridlock after 2010, when Republicans regained control of the House but Democrats remained in control of the Senate. Poor personal relations among the Republican and Democratic leaders in Congress further prevented development of a new governing coalition.

There was some chaffing among Republicans in 2011 and 2012 as it was impossible to legislate on a variety of issues. Bills would pass the Republican House and simply die in the Democratic Senate and vice versa. But Republicans were certain they would regain control of the Senate in 2012 and the White House as well, which would break the legislative logjam.

When Republican hopes were dashed last November, at least some of the more senior Republicans in Congress became receptive to working with Democrats once again. The fiscal cliff forced their hand. Rather than allow automatic tax increases and spending cuts to potentially tank the economy, Republicans and Democrats in the Senate negotiated a bipartisan deal with Vice President Joe Biden. They sent it to the House and promptly left town.

House Republicans had refused to participate in the negotiations because of philosophical opposition to higher taxes. But their hand was forced and at the last possible minute, House Speaker John Boehner brought the Senate bill up for a vote. Eighty-five Republicans joined 172 Democrats to pass the bill. The vast majority of Republicans, 151 in all, opposed the legislation along with 16 Democrats.

The question now is whether these same Republicans may be willing to break with the rest of their party again to support an increase in the debt limit, complete the fiscal year 2013 appropriations bills, and find a replacement for the $1.2 trillion sequester that was only delayed by the fiscal cliff deal. All three of these issues will likely be folded into one measure that must be acted upon by mid-February.

If we see another vote like the one on the fiscal cliff, with a third of House Republicans willing to vote with Democrats, it will be an event of potentially far-reaching importance. It may herald the creation of a moderate majority that would be the 21st century counterpart to the old conservative coalition.