As the clock ticked down to midnight last night, the attention of most professional investors was fixed firmly on the prospect that Congress would – as it did – fail to hammer out some kind of compromise that would forestall a shutdown of government offices and services.

There has been a lot of saber-rattling and brinksmanship in Washington in recent years. So much, indeed, that it may be startling to realize this is the first time a shutdown has materialized since 1996. Little wonder that in spite of all the anxiety in the headlines, financial markets seem fairly complacent. Accustomed to deals being struck at the 11th hour and 59th minute, and aware that even the sequester that came into effect curbing government spending hasn’t derailed the economy, markets wrapped up September with a healthy gain. The S&P 500 index ended the month up nearly 3 percent, giving investors a year-to-date gain of 17.9 percent (or 19.8 percent in total return)

That very fact signals a different kind of risk, however. It’s the risk of complacency: The headwinds that stocks have encountered have made this year a bumpy one for investors, but the long-term trend has been higher and higher. October 1 may be a date that changes that. Certainly, it’s a date that stands out as a kind of red line, and not just because of the government shutdown. That’s just one of the issues with which investors will have to grapple in the final quarter of the year, and it may not even be the most serious. A fresh batch of earnings announcements will be coming soon.

RELATED: FISCAL FIASCO: WILL A GOVERNMENT SHUTDOWN CAUSE STOCKS TO MELT DOWN?

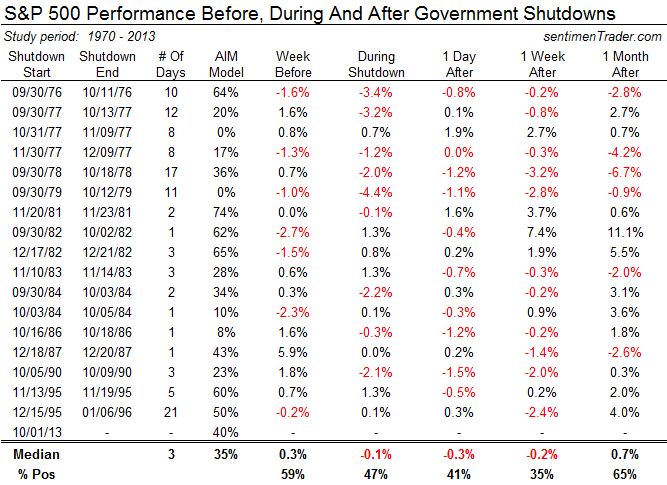

That isn’t to suggest, of course, that a government shutdown – or the prospect of another full-scale Congressional battle in only a few weeks’ time over the need to raise the debt ceiling yet again – is anything to view with equanimity. From a market standpoint, stock performance during shutdowns has been hard to read.

Over the 21 days that the government ground to a halt in December 1995 and January 1996, stock markets and the dollar were largely flat. During the longest shutdown prior to that period – 18 days, all the way back in September 1978 when the Democrats controlled Congress – stocks tumbled 2 percent, and a 12-day shutdown in 1977 left markets 3.18 percent lower. That said, it’s hard to argue that it was the shutdown that was responsible for those declines: The U.S. economy was troubled during the late 1970s, and relatively healthy in 1995, a fact that may have proved more important to investors than the shutdown.

The aspect of the shutdown that should rattle investors’ nerves is how rating agencies and global investors will respond. An increase in borrowing costs or a decreased willingness to invest – directly or indirectly – in a political system that seems to lurch from one such governance crisis to the next can’t help but take a toll on the dollar, bond markets and stocks. Americans may be scathing about the difficulties the European Union has in generating a consensus about how to tackle its fiscal problems; perhaps we, in our glass house, should refrain from throwing bricks of that kind around.

While the shutdown will dominate headlines, the significance for markets at this stage is more a matter of emotion than substance. What may end up mattering more to stock prices – even if it is less packed with drama and generates fewer banner headlines – is the fact that October 1 also marked the start of a new quarter. In only a few days, we’ll begin to see a stream of corporate earnings announcements.

While corporate profits are still growing, they are doing so at a lackluster pace: Thomson Reuters expects third-quarter earnings to rise 4.6 percent, while revenue growth has been slower still. That means that many companies still are relying on cost-cutting to generate earnings growth.

That’s why, ultimately, it’s the outlook for third-quarter earnings that you should really be worried about – and indeed, a reason to be a little more anxious, if not downright fearful, about what October and the remainder of the calendar year has in store for us. We’re sitting atop a stock market gain of nearly 18 percent, something that few market pundits would have predicted at the beginning of 2013. All things being equal, at this level and at these valuations – the S&P 500 is now trading at nearly 15 times next year’s earnings – the risk of a selloff is greater than the odds of another big rally.

The volatility index, or VIX, that measures the level of investor anxiety or fear may have risen sharply yesterday to 16.8, but that’s well below the level of 48 recorded back in 2011, when Congress was locked in an equally furious battle over the debt ceiling. It’s also nearly 19 percent below its long-term average, telling us that investors are more in danger of being overly complacent than excessively bearish, the Washington drama notwithstanding.

To the extent that the prospect of a shutdown has long-term significance for the stock market, it lies in the prospect that the lawmakers’ inability to implement sensible fiscal policy could end up taking a toll on earnings by harming economic growth. That isn’t going to show up immediately – indeed, the odds are that even a prolonged shutdown might not put a dent in earnings until sometime next year. But even if once again Congressional policymakers manage to pull off a last-minute solution to the immediate problem, there are reasons to be wary about the market at its current valuations, and to view any relief rally with wariness.