TFT’s special tribute to D-Day

There were U. S. boots on the ground in Iraq. There are, and will still be, boots on the ground in Afghanistan. Maybe there should have been cross-trainers and sneakers – or no footprint at all. Maybe those involvements were missteps.

On “liberated” ground, where the culture, mores, and indoctrinations seed an extremely different kind of turf, footfalls should be quite light – astute, enlightened. The shoes to fill would be those of Victor Joppolo, circa 1943. And he had a grounding (the footing, if you will) that made him a good fit in Italy.

A sense of turf – traction, and personal attraction

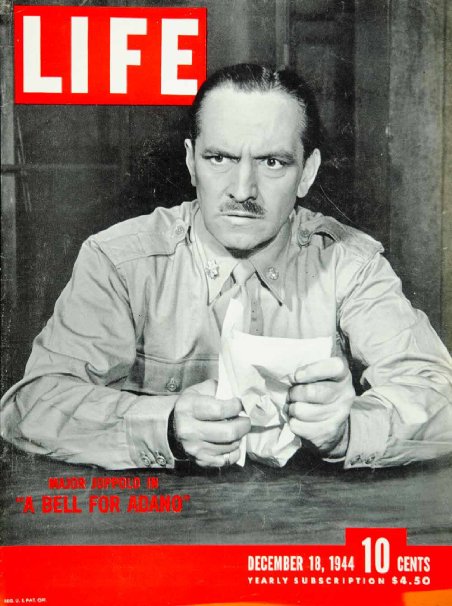

Major Victor Joppolo, the hero of John Hersey’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel A Bell for Adano, was a reconciler and a healer. Joppolo’s “residency” of cultural sensitivity and benevolence began on the heels of the combat troops that drove the Nazis and their collaborators from Sicily in July 1943. His civil ministrations supplied the antidotes, remedies, and cure for the militarism and fascism that had infected the small Sicilian coastal town of Adano. Joppolo was a healer.

War correspondent Hersey clearly intended the story to serve as clinical trial evidence of what an invading and occupying force can accomplish – with doses of civilian intelligence and empathy.

Florence Nightingale would have approved of Joppolo’s attention to sanitation and nutrition. His “training” as a clerk-administrator in New York City’s Sanitation Department provided him with some experience in orchestrating the removal of discord, along with the removal of garbage from streets and alley ways.

As he enters Adano, following the Allied invasion, Major Joppolo begins his diagnosis of the ills that have plagued the townspeople. There are alley ways infiltrated by “horse dung and goat dung, straw, melon seeds, chicken guts, and flies.” Infantry has its “clean-up” battles, Joppolo – as the town’s senior civil affairs officer (and de facto mayor) – has a different clean-up mission.

A Bell for Adano was a textbook, a manual (for the place and for the time)

The reader learns how “Mister Major” cleans up and revives the town’s economy; how he resolves disputes, removes poisonous influences, and transfuses democracy, flushing out the bile of autocracy. To the town that has suffered constrictions and maladies, he brings political dialysis.

In a grudging April 1945 review, The London Times Literary Supplement noted that the novel had made “a considerable impression in the United States,” but was “unlikely to have the same significance” for UK readers. However, the TLS allowed that the novel “should nevertheless hold interest and instruction for many. Not, perhaps, so much for the so-called lover of literature as for the so-called student of affairs.”

A Bell for Adano may have been a personal journal, a diary.

The novel, in hardcover, was one of the few volumes housed in the open-front three-shelf bookcase that was set against the wall across from my father’s knotty-pine knee-hole desk.

The bookcase served as a perch for a few framed photos, vacation memorabilia. Note pads and accounting pads lay on the bottom shelf. A baseball and a baseball glove were shelved at the midway point. There weren’t many books – probably Reader’s Digest condensed volumes, perhaps, most curiously, a Don Quixote, but no other novels that I can recall. In the corner of the sparsely-furnished room was a straight-back maple arm-chair that was not made for a bony behind.

The particular edition of A Bell for Adano is fixed in my memory. Postings on eBay and Amazon by sellers of used and vintage books reinforce exactly the picture in my mind’s eye. There’s the silhouette of the 700-year-old bell on the spine of the dust-jacket; on the brick-brown front cover, there’s a small line-depiction of the bell-tower gracing the rustic town; on the back-flap, a photo of steel-helmeted Hersey behind the wheel of an Army jeep.

Hersey “spoke” for those who couldn’t tell the whole story.

Why A Bell for Adano? A February 1944 Sunday New York Times review declared that the novel “should make the reading public and the Army sit up, take notice and possibly profit from the lessons Hersey has so adroitly woven into his narrative.” The review explained that Major Joppolo “had a genius for transforming his good intentions into achievements” – with wisdom, with a “wonderful zeal for spreading democracy,” and by “undoing the most adhesive kind of red tape.”

Had the book mirrored what my father would come to see and experience when he was in Northern France and in the Rhineland? By the time that February 1944 review was published, the man who would be my father had been in the UK 18 months as an administrative specialist with the U. S. Army Air Force.

A subsequent February 1944 New York Times review described Major Joppolo as “a genuinely good man” who was “at the same time, a believable and likable one.” The review also noted the depiction of an arrogant bullheaded bullying general “famed for his violent temper and brutal language.”

A May 1944 Book Review column explained that Hersey’s “blistering portrayal of the general is the product not of malice but of an outraged sense of human decency.” In the novel, Hersey has sergeants mis-address and then misdirect condemning paperwork, attempting to spare Joppolo from the riding-crop general’s vindictiveness.

It was Joppolo’s sergeant – no Tweet or Instagram – who calls the major’s attention to hygiene and sanitation issues. Joppolo relied on this sergeant to pick up on “dirty” dealings, and figure out who were culprits and troublemakers, and who was trustworthy. The sergeant helped identify those in need of and deserving of the major’s Public Assistance.

My father (a staff sergeant) didn’t speak about his 4 years 4 months and 26 days of service, let alone the “battles and campaigns” or the “decorations and citations” noted on his official service record.

On the very first page of the novel, Hersey tells the reader that on entering Adano, while there was no great resistance, American troops “were tight in their muscles.” That very sensation, at the least, probably coursed through my father’s fibers as he made his way through Northern France and the Rhineland; and, surely, on his day at the beach in June 1944, at Normandy. Maybe, my father thought that Hersey’s novel would speak for him.

Civics and Management Lessons: still applicable?

As the chief AMGOT (Allied Military Government, Occupied Territory) officer for Adano, the major quickly discards pages and pages of official instructions, replacing them with his own “Notes to Joppolo from Joppolo.” Among his kernels of advice to himself: “Don’t lose your temper. When plans fall down, improvise....”

Major Joppolo works to rectify the town’s commerce that has been hobbled by corruption: by extortion of taxes, tribute, and protection money under the fascists. He tries to rectify the town’s economy that has been skewed by GIs unintentionally inflating prices by paying at American rates rather than far more modest sums that were prevalent prior to the invasion.

Joppolo has to apologize and try to make amends for the destruction of property by drunkards. He has to resolve disputes between townspeople – “managing by trickery, by moral pressure, and by persuasion, to make the truth seem something really beautiful and necessary.” Astutely and humanely, he tips the balance in favor of simple justice by managing to exact honesty: “the accused would find himself telling the truth and discarding the elaborate lie he had devised.”

Joppolo has to apologize and try to make amends for the destruction of property by drunkards. He has to resolve disputes between townspeople – “managing by trickery, by moral pressure, and by persuasion, to make the truth seem something really beautiful and necessary.” Astutely and humanely, he tips the balance in favor of simple justice by managing to exact honesty: “the accused would find himself telling the truth and discarding the elaborate lie he had devised.”

Hersey allows the reader to appreciate Joppolo’s loneliness, which had very little to do with lust.

Joppolo was 35 years old when he entered Adano to take charge of its civil affairs. My father was 39 when he completed his almost four and a half years of military service. Maybe, my father thought that Hersey’s novel would speak for him.

“Speaking” to those who invade and occupy in the 21st century.

In his Foreword to the novel, John Hersey anticipates the challenges that future military involvements will pose for a country committed to democratic ways: “What Major Joppolo did and what he was not able to do in Adano represented in miniature what America can and cannot do in Europe.... no plan, no hope, no treaty – none of these things can guarantee anything. Only men can guarantee, only the behavior of men under pressure, only our Joppolos.”

These very cautions and advices were echoed in a June 2004 paper by a U.S. Army colonel who was concerned about developing “competent and adaptive” officers who would be “imbued with the skills and qualities” necessary to “transition quickly and effectively from high-intensity combat operations to stability and nation-building operations.” This colonel went on to note that “the Army cannot draft men like Victor Joppolo, so it must build them.”

In 1945, A Bell for Adano was serialized in a Russian literary magazine. Seventy years later, the novel – its prescriptions and dosages – might make for instructive summer reading in the Kremlin; and for those in our capital who would have us venture into Syria and the Ukraine.