Christine Fahlund, a senior financial planner at mutual fund family T. Rowe Price, recently presented a novel retirement strategy for a 60-year-old with an inadequate nest egg. Stop putting money into a 401(k). Instead, spend it on cruises and visiting the grandkids. It’s a slacker’s dream come true: Fahlund’s strategy yields 70 percent more retirement income than is available to an otherwise identical 60-year-old who saves like a Calvinist for the remainder of his career. That’s right. More income.

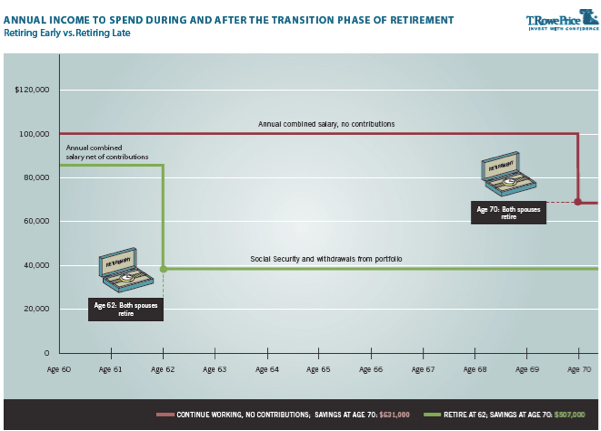

There’s a catch, obviously, and it’s this: The slacker stays on the job to age 70, while the Calvinist retires when most Americans do, at 62, the age at which you first qualify for Social Security retirement benefits. Why does that work? Because delaying retirement delivers a triply-virtuous whammy — eight more years for existing savings to grow, eight fewer years of retirement to provide for and a bumped-up Social Security benefit. Sure, the slacker would be even better off if he’d saved a little in his 60s, but Fahlund was making a point: “People tend to see working longer as a defeat and a burden. We’re suggesting you could actually see it as an opportunity.”

If only policy makers and employers could see it the same way. For years, researchers have been pointing out that working later is the only palatable way around the looming retirement income crisis. Maybe, as Fahlund suggests, it’s time to stop fighting the inevitable and embrace it. It would solve a whole lot of problems: Keeping workers on the job a few years longer would not only keep baby boomers out of poverty, but would also help the economy grow, reduce the deficit and hand employers what they say they want most — a more flexible workforce.

No one is asking older Americans to stay at their desks until they’re carried out feet first. A 2008 McKinsey Global Institute study, best known for estimating that two thirds of baby boomers would come up short for retirement, calculated that lifting the average retirement by just two years would cut the ranks of at-risk boomers in half. Alicia Munnell, head of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College and author with Stephen Sass of Working Longer, reached the same conclusion. It’s that virtuous triple whammy at work again: “When we tell people to work longer, they often say, ‘I can’t work until my 90s!’” laughs Munnell. “But they don’t have to. Working two to four years longer makes a huge difference.”

Convincing workers to put in an extra two to four years on the job isn’t hard, since nearly three-quarters of employees 50 to 71 say they’d like to keep working in retirement. In reality, though, most don’t. Peter Cappelli, director of the Institute for Human Resources at Wharton and author with Bill Novelli of Managing the Older Worker, says the problem lies with employers. “Most of the reasons older workers can’t find opportunities to keep working have to with employer’s misperceptions,” he says. “These are so widespread and so unfounded that they deserve to be called myths.” Among them:

Older workers don’t perform as well as younger workers. While some physical and mental abilities may decline with age, the effect on workforce performance is far outweighed by older workers’ virtues: more experience, superior interpersonal skills, less absenteeism, less turnover and better rapport with customers. Write Novelli and Cappelli: “The overall conclusion from all the research [on age and employability] is that for virtually all jobs and all circumstances, workers with more experience are almost always better performers. Any negative effects of age on performance are so minor as to be irrelevant.”

Older workers cost too much, mainly because of health care. It’s true that older workers’ per capita health costs are 1.4 to 2.2 times more than those for younger workers, according to a study by benefits consulting firm Towers Perrin for AARP. But remember: Most employers give benefits for employees and their dependents. Older workers tend to have few dependents, because children are out of the picture. Older households’ health care costs can actually run less.

Older workers don’t fit in with the demands of the modern workplace. In fact, retired workers are ideally suited to the flexible 21st century contingent workforce. “What employers are after with contingent employment is a just-in-time workforce that is ready to contribute immediately, that doesn’t need to be trained, and that is willing to be brought in and let go on short notice in order to respond to uncertainty in the business environment,” says Cappelli. “That sounds exactly like what older workers can offer.”

If employers can be persuaded to get over their ageism, economic policy makers should quickly fall into line. After all, seniors who work and pay taxes shrink the deficit and, in some scenarios, add to the solvency of Social Security and Medicare. Perhaps more important, they increase workforce participation and economic output. McKinsey estimates that lifting the average retirement age by two years would add $13 trillion to cumulative GDP over the next 30 years.

A little behavioral nudging and good old-fashioned tax incentives can encourage employers and workers to do the right thing. Munnell suggests gradually raising the age at which Social Security benefits are first offered from 62 to 65, eliminating the temptation to take the money and bolt for Florida. David John of the conservative Heritage Foundation suggests eliminating Social Security payroll taxes for workers who work past the normal retirement age — and for the employers who hire them. McKinsey suggests pruning the thicket of pension, tax and age discrimination rules that prevent companies from offering part-time contract work to older workers after they’ve retired.

Breaking down the modes of thinking that keep older workers sidelined will take some change of heart, particularly among employers. But it can be done: Finland raised the average retirement age of its workforce by nearly four years in less than a decade. And lest we forget, Americans once were quite certain that women had no place in the workforce. The beauty of keeping older Americans at work is that it gives everyone — seniors, employers and policy makers — what they say they want. Sometimes the best policy is just to find a way to take yes for an answer.