Just under a year ago, Mitt Romney was looking at what promised to be a rough evening in Tampa, the same city where he will formally accept his party’s presidential nomination this week. At the time, that prize seemed to be slipping from his grasp. Polls showed Romney badly trailing Texas Gov. Rick Perry, a late entry into the race who was a matinee idol of the right. And the rowdy crowd that had gathered for a tea party-sponsored debate at the Florida State Fairgrounds was clearly in the mood for a rumble.

"You’re going to get booed," Romney strategist Stuart Stevens recalls warning his candidate as they watched a television in a nearby trailer and assessed what awaited in the hall. The former Massachusetts governor responded with a big, deep chortle. "It’s happened before," he said.

But that night Perry was the one who got the catcalls, for being insufficiently tough on illegal immigrants. Romney was at his best, steady and confident as he tore apart Perry’s contention that the sacrosanct Social Security system is a "Ponzi scheme." He left the stage having done what he wanted, which was to sow doubts that the swaggering Texan was the best candidate to go the distance against President Obama.

Romney wasn’t out to make Republicans love him. He was out to prove to them that they didn’t have to.

RELATED: Tea Party Libertarians Win Big in GOP Platform

That was the thing his more flamboyant rivals failed to understand about the complicated relationship Romney has with his party. It was why their constant attacks on his past apostasies, the biggest being the Obama-like health care law he passed in Massachusetts, failed. Not even Romney’s own limits as an orator and campaigner tripped him up.

"Republicans convinced themselves he was acceptable, if not exciting," said former House speaker Newt Gingrich, another GOP primary contender who enjoyed a brief reign at the top of the polls. "His Teflon was ‘I can beat Obama,’ and Republicans said, ‘That is enough for me.’ The base’s pragmatism, even in the dogmatic tea party era, was underestimated by everyone who ran against Romney, including by me," Gingrich said.

But it is also true that this year, the name at the top of the ticket is not what defines the GOP identity as it has at times in the past. Some presidential candidates reshape their parties, as Ronald Reagan did in 1980, Bill Clinton in 1992, George W. Bush in 2000.

Romney fits more in the category of those who, with more mixed success, have run as true standard-bearers. Think Walter Mondale in 1984, George H.W. Bush in 1988, Bob Dole in 1996. The Republican brand these days is stamped on Capitol Hill. Romney shows no sign of setting himself apart from that agenda, as unpopular as it is among independent and swing voters.

Months before Romney tapped Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) for his presidential ticket, he endorsed the House Budget Committee chairman’s controversial fiscal blueprint, which includes a plan to drastically overhaul Medicare. Anti-tax activist Grover Norquist predicted: "If Romney is president, he will sign a bill that looks very much like Ryan, and we will call it ‘the Romney revolution.’"

Republicans, moreover, are seeing Romney as a transitional figure rather than a transformational one.

A year ago, it seemed that every GOP gathering was paying tribute to the centennial of Reagan’s birth. But Romney’s nominating convention will throw a spotlight on the next wave of conservative talent — not only his running mate, but also New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie; Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida; Ted Cruz, the tea party Senate candidate from Texas who upset the establishment pick; Virginia Gov. Robert F. McDonnell; Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker; South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley; Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal.

"This new generation signals the future of the party," said Ralph Reed, the longtime GOP operative who heads the Faith and Freedom Coalition, an organization that aims to mobilize evangelical voters. "Romney is both the midwife of and the beneficiary of their talent," Reed added. "And if he wins, they will spend the next four or eight years working with him, serving in his administration, and not incidentally, jockeying to succeed him."

But first, Romney must get elected. Between now and November will be a four-day infomercial from Tampa, in which he will have a chance to reintroduce himself to a broader audience; three presidential debates; and a day-by-day slog that is getting nastier with every new campaign commercial.

RELATED: Obama's Real Presidential Swing State: Greece

"The question for Mitt is how to grow beyond the primary and broaden his appeal. The convention will be an opportunity for that," said GOP consultant Mike Murphy, who worked on Romney’s successful 2002 gubernatorial campaign and remains in touch.

In a Time Magazine column last week, Murphy urged his old client to use the Tampa gathering, which has an expected audience of 20 million households, to "revise his pitch and start talking to general-election voters."

There are no indications — talk of Etch A Sketches aside — that Romney will do that by trimming his positions. Nor is he distancing himself from a party that has moved to the right and has become as ideologically united as at any time in memory. On Friday, Romney even ventured to the fringe of the GOP with a clumsy joke that indulged those who contend Obama was not born in America.

With his surprising decision to run with Ryan, the intellectual leader of the conservative forces in the House, Romney has framed the election as more than just a referendum on the current occupant of the Oval Office. It will also be a choice between two starkly different governing philosophies.

MIRROR IMAGE OF 2008

That Romney’s second run for the nomination succeeded is testament, in large measure, to the way he retooled his approach to politics after his defeat four years ago. His 2.0 launch reflected both the lessons he learned from the past and the calculations he made about what lay ahead. As Romney often says when talking about his business career, he is a man who can count his share of mistakes. But those who have watched him closely know that rarely does he make the same one twice.

Romney’s campaign this year is headquartered in the same dingy Boston waterfront building as it was in 2008, but everything else about the operation has been overhauled. "This race was a mirror image of 2008," said Doug Gross, who was Romney’s Iowa chairman that year but did not re-up this time around.

Despite speculation that the rise of the tea party would rewrite the playbook for winning the nomination, Romney decided early on a cautious, relatively conventional strategy. Then he waited for each of his rivals in a weak field to self-immolate as they battled it out, a process helped along by the millions of dollars in negative ads that the outside super PAC Restore Our Future aired on his behalf.

"He is a manager who sticks with his strategies and implements them relentlessly," Gingrich said. In his second run for president, Gingrich added, Romney has proven to be "much more stable, much more methodical. I think, in a way, calmer."

That discipline was on display the day after he formally announced his second bid for the presidency in June 2011, when Romney joined the lineup of GOP hopefuls who appeared before Reed’s politically oriented Christian conservative group in Washington. It was a potentially tense situation, given the mistrust that evangelicals have of Romney’s Mormon faith. Many expected him to try to win over his audience by speaking of the commonalities of their religious beliefs.

RELATED: The Real Mitt Romney: What You Didn't Know

Instead, Romney gave his standard stump speech, emphasizing unemployment, declining home prices, debt, foreclosures, and reminding the group of their shared foe: "Barack Obama has failed the American people." Romney was the only presidential candidate that day, other than libertarian Rep. Ron Paul (R-Tex.), who did not salt his address with frequent references to God.

It helped, of course, that talking about the economy played to Romney’s strengths and his background, that it underscored Obama’s greatest vulnerability, and that it happened to be at the top of voter concerns.

"Mitt Romney is a guy who, as they said at Bain [Capital, the private equity firm he founded], could see the trend line," said John Weaver, a top strategist for former Utah governor Jon Huntsman, another primary challenger. "He got ahead of the curve far enough, and well enough, that he became acceptable to the base of the party."

After his failed presidential campaign of 2008, aides say, Romney dedicated himself to figuring out what had gone wrong. He realized he had erred by trying to be all things to all Republicans — delivering an economic message when he was in front of local business groups, stressing his values before religious ones. He had angled to land on the right of his rivals on every front and to catch a wave with every news cycle.

His Iowa chairman Gross phoned the Boston headquarters on Thanksgiving Day 2007, just weeks before the caucuses in which Romney’s campaign had invested $10 million, hoping to launch the primary season with a victory. "Who is it we’re trying to get?" Gross recalled asking. But he said he couldn’t get an answer: "They never figured it out."

RELATED: Conservative Super PACs Outraised Liberals 3 to 1

Romney came in a distant second in Iowa to former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee. One month and four days later, he was out of the race, his $97-million candidacy — nearly half of which was financed out of his own fortune — amounting to barely a speed bump on John McCain’s ride to the nomination.

Romney had offered a fuzzy, off-the-rack kind of Republicanism that only served to reinforce the party’s doubts about what he really believes, given his more moderate positions in the past on issues such as abortion and gay rights. When Romney lost, "he was really frustrated, mostly," recalled Beth Myers, who was his campaign manager in 2008 and led his vice presidential search this year. "He felt that he had never been able to talk about his vision for the country."

Then there were the tactical blunders. In 2007 and 2008, Romney spent heavily on a "win early and win often" strategy, which left him no room or resources to recover from his loss in Iowa. He had also built a huge operation and hired legions of strategists, assuming that — as had been the case in business — reams of data and a diversity of viewpoints would yield the right answer. Instead, his political enterprise turned into a high-priced, feuding mess.

This time, he would run a smaller, tighter operation, shuffling some key aides and shedding others. He would not waste his money trying to win meaningless rituals such as straw polls or state primaries known as "beauty contests" where delegates were not awarded. He would build his operation for the long haul he saw coming. "They were very clear that they saw this as nothing but a war of attrition," said Gross, who discussed the early 2012 strategy with Romney’s team.

A YEAR OF GATHERING CHITS

During the off-season, Romney borrowed a page from one of the greatest comeback stories in modern political history. As Richard M. Nixon had in 1966, Romney hit the campaign trail during the 2010 midterm elections to gather chits and help position himself as the presumed front-runner in 2012.

In 2010, Romney made 33 appearances for congressional candidates and nearly 60 for state and local ones, visiting more than 30 states. His political action committee contributed $1.16 million to candidates and party organizations, ranging from high-profile gubernatorial and Senate races to statehouse candidates to county GOP operations.

He also made some unorthodox moves — for instance, bestowing an early endorsement on Nikki Haley, then a long shot in a bruising South Carolina Republican primary for governor. It was in part a gesture of gratitude to one of the few South Carolina GOP officials who had supported him in 2008. But it gave Haley a crucial boost of credibility against her better-known opponents.

"It was not the politically safe thing to do," recalled Tim Pearson, who was then Haley’s campaign manager. "Governor Romney coming in and taking what people thought was a political risk changed what folks in the state, in the donor class, thought about Nikki Haley." And when she won, she proved to be a loyal ally — though it was not enough to prevent him from getting trounced in her state by Gingrich.

Those who are close to Romney said he went through another exercise that proved to be far more significant than was generally realized. Starting in 2008 and continuing through most of 2009, he wrote a book. His wife, Ann, had been diagnosed with breast cancer and wanted a change of scenery and climate for her treatment. The couple sold the house in Belmont, Mass., where they had raised their five sons, and moved to a beachfront property in La Jolla, Calif. Romney exulted to friends about how he could hear the sound of the waves as he wrote.

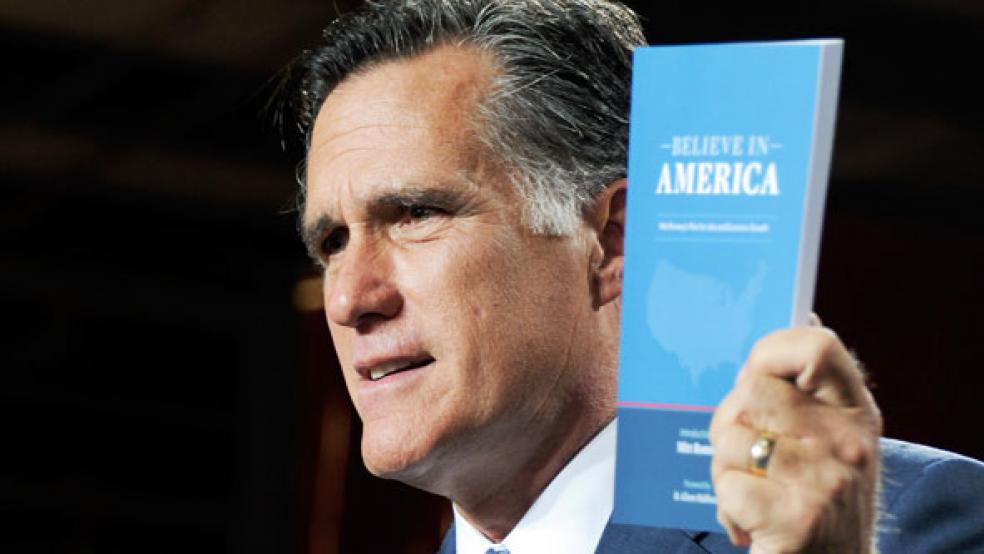

No Apologies turned out to be a very different book from the one that he had written in advance of his 2008 race. That earlier one, Turnaround, was an account of his takeover of the scandal-ridden 2002 Winter Olympics, and read like one of those volumes that line the shelves of the management and leadership sections at the bookstore. No Apology, published in 2010 and featuring a slightly grayer Mitt Romney on the cover, was his manifesto, a dense read with chapter titles such as "Why Nations Decline" and "A Free and Productive Economy."

"He felt very clear, having written the book, about what he thought the prescriptions were," said Robert White, a partner of Romney from his Bain Capital days who remains one of his closest friends and advisers.

Romney stayed within the bounds of Republican orthodoxy, but some of his ideas were edgy, especially amid economic uncertainty. In 2008, Romney was accused of pandering when he told auto workers in Michigan and textile workers in South Carolina that he would "fight to save every job." In his subsequent book, he championed "creative destruction" — the downsizing and restructuring of businesses to make room for innovation. That left an opening for his opponents to remind voters that his work in private equity had been on behalf of investors, not the workers of the companies he acquired.

In New Hampshire, Gingrich accused Romney of having "looted" companies; in South Carolina, Perry said Romney had gotten rich off "failures and sticking it to someone else." But both of Romney’s rivals ended up finding themselves on the defensive for rhetoric that, to Republican voters, sounded anti-business. That was part of the Teflon that Gingrich described — the base did not want to hear language that might come back to haunt their ultimate nominee.

In picking Romney, the increasingly conservative Republican Party voted with its head, rather than its heart. Some worry about the consequences if that bet turns out to have been wrong. "If he is not successful, holy Toledo, there will be hell to pay in this party. The right wing is going to drive further right," said Gross, Romney’s former Iowa chairman.

But that may happen even if he does win. For the Republican Party has decided that Mitt Romney is the means to an end. Which is exactly the point he has been making all along.

Research editor Alice Crites of The Washington Post contributed to this story.