China Daily, an English-language newspaper published in Beijing, recently reported that more than 400 million Chinese are studying English. Why? Because English is the official language of 63 countries. More than 80 percent of all technological information is published in English and it is the language of almost all software source codes. It’s essential that anyone hoping to compete in the global economy master English.

China is not unique. A recent piece in The Wall Street Journal portrays the Japanese embracing English like a drowning man hugging driftwood. The CEO of Japanese online retailer Rakuten has mandated that English must be used for all work documents and for signs in the company cafeteria. Anyone not able to speak and write English by 2012 will be fired.

In Europe, too, for multinationals like Mercedes Benz , and indeed all over the world, English has become the lingua franca of commerce and a passport to the future. All of which makes it peculiar that we in the U.S. are not teaching our own citizens to speak English. Instead, in this era of budget squeezes and teacher layoffs, we continue to pour hundreds of millions of dollars down a drain labeled “bilingual education.”

Despite studies questioning the effectiveness of bilingual programs, they persist in several states and are supported by the federal government. The fiscal 2010 budget appropriation for the Office of English Language Acquisition totaled $750 million and the request for the upcoming year is $800 million. In many programs, children are taught in their native language in separate classrooms. Introduced via Congressional legislation in the 1960s in an effort to ensure schooling for our growing immigrant population, bilingual education quickly became a trap that robbed many children of the opportunity to catch up to their English-speaking peers.

Dr. Rosalie Porter has served on the front lines of the battle over bilingual education for nearly 30 years. She herself arrived in the United States from Italy in 1936 at the age of six, not speaking a word of English. Formerly a bilingual teacher, she headed the Institute for Research in English Acquisition and Development in Washington, D.C., for a dozen years, edited its magazine READ Perspectives, and served as chairperson of the Massachusetts Commission on Bilingual Education. Her view is simple; bilingual education is a “wrong-headed theory” that doesn’t work. Her preference is an approach called “structured immersion,” where children initially are taught English in separate classrooms for part of the day, along with others who grow up speaking a different language at home, but are quickly thrust into classrooms where the teaching is in English.

“Most children in structured immersion can get up to speed in two years; with bilingual education, we’ve seen that it takes kids three to six years to mainstream,” Dr. Porter said in an interview with The Fiscal Times. She acknowledges that the debate is an emotional one, with some proponents of bilingual classes charging opponents with racism and ethnic insensitivity. “The teachers’ unions should have come out against bilingual education, but they’re afraid of the politics of immigration,” Dr. Porter said.

Not only does the discourse trip over issues of ethnicity, it also wanders into the emotional squabble over spending on education. ProEnglish, a nonprofit organization in Arlington, Va., dedicated to promoting English as our national language, asserts on its Web site that federally funded bilingual programs “generate teaching and administrative jobs as well as higher salaries and more spending,” dampening dissent. “I’ve never been against spending money to help kids, but the money should be spent in an efficient, effective way,” said Dr.Porter, who is on the ProEnglish board of directors.

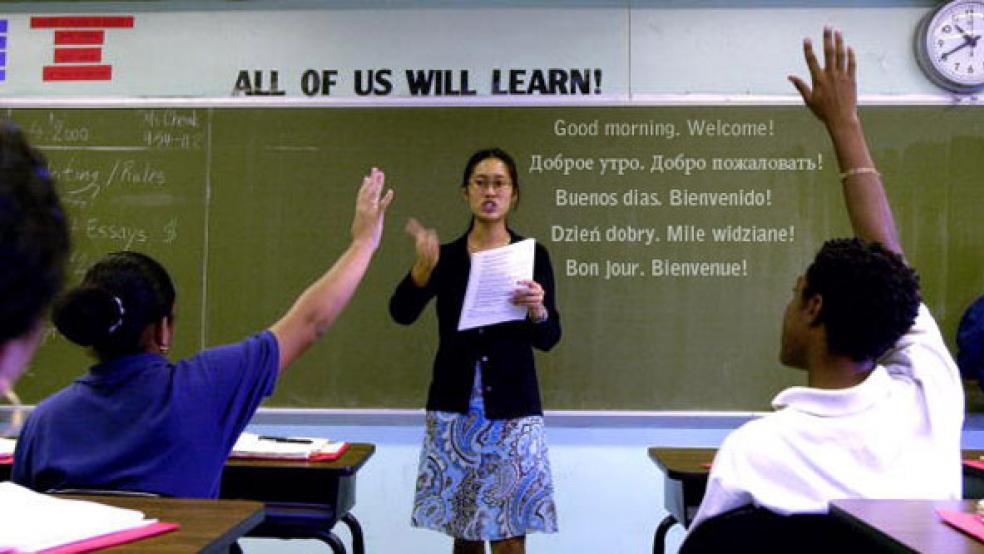

These days, many educators have come around to Dr. Porter’s preference for “structured immersion.” Since 1998, Arizona, California and Massachusetts have thrown out bilingual education in favor of structured immersion. Parents, too, are on board. Polls show that parents don’t need convincing; they know that speaking English is essential for the success of their children. However, certain states, including Texas and Illinois, continue to keep children quarantined by language.

In Texas, more than 400,000 children were taught in Spanish during the 2008-2009 school year. According to a study by Boston University’s Christine Rossell, “Texas schools with a bilingual program spend $402 more per student than schools without a bilingual program. Other studies find that bilingual education costs $200 to $700 more per pupil than alternative approaches.” Dr. Rossell’s research also concluded that “bilingual education in Texas has a negative effect on English-language learner achievement.” With the Hispanic population in Texas expected to soar from 6.6 million in 2000 to more than 13.4 million in 2025, how the state’s schools bring these kids into the mainstream will become an ever more pressing and costly issue.

As goes Texas, so goes the nation. Fully one quarter of kindergartners in this country are Hispanic today. According to a recent Associated Press-Univision poll, these youngsters are three times more likely to drop out of high school as the rest of the population, which makes it harder for them to get jobs. This hurts the Latino community, and it hurts the U.S. These days, when teacher jobs are at risk, and the federal government is looking for ways to cut costs, continuing to support bilingual education is absurd and unfair. As Dr. Porter says, “kids should not be separated by language and ethnicity; they’ll never catch up.”