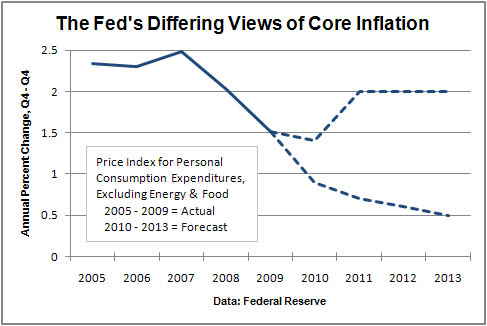

• Core CPI inflation dropped to 0.6 percent in October, a record low. • The economy grew a revised 2.5 percent in the third quarter. • Fed policymakers, on average, expect core inflation of 1.4 percent in 2013. |

It is a truly unusual moment in American economic history when so much attention is given to both inflation and deflation — simultaneously. The forces that generate unacceptably high inflation are so opposite from those that create undesirably low inflation, or even deflation, that worrying about both at the same time seems odd. What’s becoming increasingly clear, however, is that over the next year or two, at least, neither is likely to rear its ugly head.

Nearly all economists agree that U.S. policy over the last year or two has been properly focused on avoiding deflation, a downward spiral of prices that can cripple an economy by discouraging production and employment. A quick glance at October price indexes shows why. Outside of the ups and downs in energy and food, the annual inflation rate for the two most widely followed price indexes is headed straight down. Core inflation, measured by the consumer price index, fell to only 0.6 percent last month. The Federal Reserve’s preferred gauge, the price index for personal consumption expenditures, dipped to 1 percent. Each index had peaked at about 2.5 percent about two years ago, and both now stand at the lowest levels since monthly records have been kept over the past half century.

The good news: The upturn in the economy and recent additional support from the Fed’s purchases of Treasury notes, are strengthening the economy, easing the downward pressure on prices and greatly reducing the risk of deflation. “The backdrop of an improving growth outlook, a weaker dollar and signs of some pipeline price pressures leave us comfortable with the view that the risk of outright deflation in the core CPI remains small,” says economist Peter Newland at Barclays Capital.

The stronger tone of most economic data in recent months, suggesting a rebound from the soft patch this summer, is adding support under prices. The Commerce Dept.’s upward revision to third-quarter economic growth, to 2.5 percent from 2 percent reported a month ago, showed that spending by both consumers and businesses was stronger than first estimated. Growth in household income from wages and salaries also was revised up substantially in both the second and third quarters, and corporate profits posted another solid advance. Importantly, household spending has grown at a progressively faster pace in each quarter this year, indicating building momentum.

Further back in the production process, core inflation for wholesale prices of goods headed to retail markets has been heading up this year. How much of that pickup gets passed along to consumers in coming months will depend on how much discounting retailers will have to do to move holiday merchandise, but retailers seem optimistic. Plus, standard rules of thumb say that the dollar’s 5 percent decline in recent months will lift prices of imported goods enough to add a few tenths of a percentage point to core consumer inflation, even as rising commodity prices for food and energy add a pinch to overall inflation.

Economists generally agree that, with proper policy, avoiding deflation is the easy part of the Fed’s task. Even in economies with high unemployment and other idle resources — forces that put downward pressure on prices and wages — it is difficult to push the inflation rate below zero without a particularly harsh series of shocks, says economist Andre Meier in a study at the International Monetary Fund.

Meier says that declines in core inflation tend to peter out as the inflation rate approaches zero. One reason: outright declines in wage rates and salaries are rare in advanced economies, making any downward spiral in wages and prices difficult to get started. Already, the slowdown in hourly wage growth appears to be moderating. Another factor working against deflation is the solid anchoring of inflation expectations that comes with the credibility of the central bank’s commitment to preserving price stability.

The Fed’s more difficult challenge, at least over the next couple of years, will be to foster economic conditions that will return inflation to the 2 percent or so level that policymakers believe is consistent with price stability and a smoothly-functioning economy. Even that modest pickup in inflation could take a long time. Economists believe it would take a burst of 4-to-5 percent growth over the next couple of years — a pace almost no one expects — to soak up all the idle workers, vacant real estate and excess factory capacity. Barring that, upward pressure on prices will remain weak, with only slow progress in reducing unemployment that could leave the economy vulnerable to any new shock.

Those concerns are evident in the minutes of the Nov. 2-3 meeting of the Fed’s policy committee, which included a summary of economic projections by 18 committee members. Some policymakers think inflation will return to close to 2 percent as soon as next year, while others believe it will remain close to 1 percent, or lower, until 2013. Overall, though, the committee appears to recognize the task before them. A weighted average of their forecasts shows core inflation rising from 1 percent this year to only 1.4 percent by the end of 2013. That would leave the rate well below the Fed’s desired level a full three years from now.

The inflation-deflation debate and the appropriate direction of Fed policy will not go away anytime soon. Even under current economic conditions, amid high unemployment and disappointing growth, worries about a rise in inflation to an unacceptably-high level are valid — but only well into the future. Even then, the risk is small, especially since Fed officials and private-sector economists alike believe the Fed has the tools and the time to withdraw the excess funds it has added to the system. In the meantime, the chances of the economy falling into deflation have diminished substantially.