• New home sales are down 29 percent from a year ago. • The total potential inventory of unsold homes is6.3 million. • 54 percent of HAMP mortgage modifications ended in re-default. |

Lest we forget, amid worries about jobs, the deficit, European debt, and all the other issues weighing on the economic outlook, the housing bust continues to exert its own special drag. Despite the broader recovery and generally improved financial conditions, the housing market and housing finance are still broken. Past policy efforts helped pick up the pieces, but that’s about all. Looking toward 2011, the best that can be said is that some key market fundamentals are headed in the right direction, but too slowly to imply any meaningful improvement over the next year.

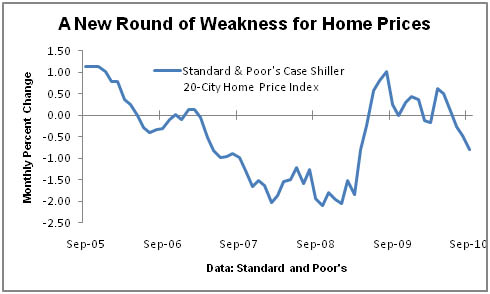

As in nearly all markets, the bottom line comes down to supply and demand, and the recent trend of prices reflects the imbalance. After being propped up by two rounds of home buyer tax credits, prices are falling again. The Standard & Poor’s Case-Shiller index dipped in September for the third month in a row, the most recent data available, as weak demand, heavy inventories and the steady flow of new foreclosures reasserted their pressure on prices.

|

On the demand side, even low mortgage rates aren’t helping much. Sales of new and existing homes are still 29 percent and 26 percent, respectively, below year-ago levels and 80 percent and 39 percent below their respective 2005 peaks. The problem is tight mortgage lending conditions, even for borrowers who are not out of work. Analysts at Morgan Stanley note that lenders now require down payments averaging 20 percent or more compared with little or nothing before the bust, and required credit scores have jumped.

Plus, lenders’ fear of "put-backs," or securitized loans that revert back to the mortgage originator in the event of default, is also restricting credit. Lenders control that risk by seeking only high-quality borrowers with clean credit and ample equity in their homes. Currently, one in four borrowers owes more on their mortgage than the value of their home. "As housing is a leveraged investment, a decline in credit availability has a much more powerful impact on housing demand than a rise in mortgage rates," says Morgan Stanley economist Richard Berner.

The supply-side issues are much thornier. The total number of homes expected on the market in the coming year is little more than guesswork. Banks are keeping many previously-foreclosed homes off the market, even as new foreclosures continue to mount, creating a shadow inventory that threatens to depress prices further. Hard data say that more than four million new and existing homes are on the market and unsold, but according to CoreLogic’s latest tally there are another 2.1 million homes either in foreclosure, at least 90 days past due, or taken by the lender and not yet listed for sale. That is a total potential inventory of 6.3 million homes in the coming year, which represents a 23-month supply at current sales rates, more than triple the level consistent with a healthy market.

The excess can be eliminated by the fourth quarter of 2011, which would stop the downward pressure on prices. But that projection doesn’t account for the shadow inventory.

Another way to look at the pressure on prices is the number of vacant homes for sale. The homeowner vacancy rate stood at 2.5 percent in the third quarter. Economists at UBS estimate that the rate needed to stabilize prices is between 1.7 percent and 1.8 percent, implying an excess of about 580,000 homes that are vacant and for sale. Given conservative projections for household formation, replacement demand and new construction, they gauge that the excess can be eliminated by the fourth quarter of 2011, which would stop the downward pressure on prices. But that projection doesn’t account for the shadow inventory.

Despite the looming threat of more foreclosures, the price impact of the shadow inventory may not be as large or as widespread as feared. The number of vacant homes held off the market by banks, which show up on their balance sheets as REO or real estate owned, has jumped 30 percent since 2006. Still, UBS says banks appear to be selectively managing their inventories with the intent of minimizing the negative impact on local-area prices, instead of dumping them willy-nilly onto the market. Banks have a clear incentive to manage their sales of REO properties, especially as job markets improve, which will boost future demand.

Direct policy efforts so far have been concentrated on mortgage modifications and refinancing, involving write-downs of loan principles and loan forgiveness. A Federal Housing Authority program is aimed at forestalling defaults by homeowners who are underwater but still-current on their payments, while a revamped Home Affordable Mortgage Program (HAMP) is focused on already-delinquent borrowers. The goal is to mitigate defaults, but results are not encouraging.

One thing is clear. While housing led the economy into a recession, it will not lead it out.

An October report on HAMP shows that of the 1.4 million homeowners who have begun trial modifications, 54 percent have re-defaulted. The FHA program has been in operation for only about three months. Morgan Stanley’s Berner says programs like HAMP can be helpful. "Unfortunately," he says, "they do not address the fundamental supply-demand imbalances in housing, and they are not widely available."

Perhaps the key factor in how fast that imbalance is eliminated is the job market. Stronger job growth enhances housing demand, reducing inventories. It forestalls defaults, limiting additions to inventory, and it strengthens credit quality, facilitating lending. Moreover, the pace of job gains is essential in creating new households. Already, builders have cut housing starts so drastically that they are running far below household formation, a gap that is sure to widen further in 2011, helping the market move toward balance.

One thing is clear. While housing led the economy into a recession, it will not lead it out. Until the labor markets are strong enough to start repairing the economy’s most visible and most damaged sector, the economy’s progress just won’t look like, or feel like, a recovery.