|

The fiscal debate now raging in Washington is about to enter a new phase: Investors in U.S. government debt around the world may soon get pulled into the fray. If the current political wrangling boils over in coming months, raising fears of a government shutdown or the inability of Washington to meet its obligations, investors are almost certain to demand higher interest rates to hold Treasury securities. Higher rates would pose yet another challenge for economic growth in 2011, on top of recent Mideast turmoil and the surge in oil prices.

The first critical date could be days away. Despite President Obama’s presentation of his 2012 budget proposal on Feb. 14, Washington still does not have an official spending plan for fiscal year 2011, which began on October 1, 2010. The government is operating under a continuing resolution that will expire on Mar. 4, and while Republicans and Democrats appear close to a deal for a two-week extension, talks about anything beyond that have been contentious. Without a new continuing resolution, the government will not have the authority to spend the money needed to provide services. Failure to pass a new resolution would effectively shut down certain government operations.

The more important date will come later this spring or summer, when Washington will hit the $14.3 trillion statutory limit on the amount of outstanding debt it can issue. Even if a new continuing resolution authorizes new spending, hitting the debt ceiling would limit the government’s ability to meet its obligations. The Treasury Dept. has said the ceiling will be reached between April 5 and May 31. Economists say the Treasury could take extraordinary measures, such as selling certain assets, to stretch the limit another couple of months, but such actions, they say, might severely disrupt the credit markets.

Investors around the world will be watching. Holders of Treasury securities are already skittish about sovereign debt problems in Europe, and the rancor in Washington only focuses more attention on the unsustainable trajectory of U.S. finances. “The greatest risk around the upcoming debt ceiling debate is that an action or event is mistakenly viewed by investors as a sign that the U.S. government does not intend to honor its obligations to debt holders,” says UBS economist Drew Matus.

Bond guru Bill Gross, head of the $241 billion PIMCO Total Return Fund, is more blunt. He recently told the Associated Press that the budget war signals to countries holding Treasuries that their assets are hostage to a rogue Congress. Gross has already cut PIMCO’s Treasury holdings to the lowest in two years. The fear is that, without a quick resolution of the debt limit issue, more uneasy investors will start dumping Treasuries. The resulting increase in Treasury yields would push up long-term borrowing rates broadly and put a dent in the economic recovery.

Even if political head-butting causes the Treasury to hit the debt limit, an outright U.S. default on its debt by missing an interest payment is next to impossible. The government takes in mountains of cash every day that far exceed the interest payments it must make. However, it would have to cut back on some of its non-interest outlays, perhaps by delaying tax refunds or Social Security checks. While not a “default” per se, the message to credit markets would be a wave of uncertainty about the government’s ability to function and meet all its obligations.

Comparisons have been drawn to the 27-day government shutdown in late-1995 and early-1996, when President Clinton vetoed a Republican budget bill that would have authorized continued funding for government programs. But while having enormous political significance, that shutdown had little economic or market impact.

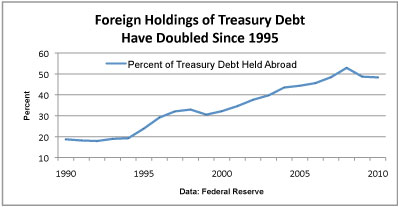

This time would be very different. The 2011 federal deficit is projected to be $1.6 trillion, or 10.9 percent of GDP, compared with $164 billion, or 2.2 percent of GDP, in 1995. The government’s marketable debt, that portion held by the public, in 2011 is projected at 72 percent of GDP vs. 49 percent in 1995. The most important difference is that overseas investors now hold 48 percent of marketable Treasury debt, double the 24 percent they held in 1995, according to Federal Reserve data. Heavy foreign holdings could heighten fears of reduced demand for Treasuries and amplify any market reaction to Washington’s fiscal impasse.

The current fiscal battle is also detracting from the potentially positive market impact of the proposals set forth in Obama’s2012 budget, which would result in deficit savings of $1.1 trillion over the next decade, cutting the deficit to just over 3 percent of GDP in the next five years. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner told the Senate Budget Committee on Feb. 17 that the plan tells the world the U.S. is beginning to address its fiscal situation, a message that would produce “a dramatic improvement in investor confidence about the political will in Washington to deal with these problems.”

In addition to the immediate concerns, interest rates also pose a potential threat in the long run. They are perhaps the biggest wildcard in any budget outlook. As the volume of marketable federal debt rises, small fluctuations in rates can have a big impact on future deficits. Deficit projections 10 years ahead are usually a shot in the dark subject to a host of variables, but even if Obama’s 2012 blueprint were to play out, debt would rise by about $8.3 trillion, to 77 percent of GDP in 2021.

Assuming what analysts at Barclays Capital believe is a more likely scenario, debt could easily end up at more than 90 percent of GDP. If so, they show that a swing in financing costs of only two percentage points over the next five years, from 4 percent to 6 percent, would lift interest payments on the debt by 2021 from 16 percent of revenues to 25 percent of receipts. That would be equivalent to three-fourths of all discretionary outlays. “At this point,” the analysts say, “the U.S. is more exposed fiscally to a small change in interest rates than at any point over the past few decades.”

The sad fact is that the current fiscal confrontation could end up slowing U.S. growth, cutting into federal revenues, and raising the cost of financing the U.S. debt. Hopefully, the policymakers on Capitol Hill understand that a lot has changed since the budget battles in 1995.

Related Links:

To Raise or Not Raise the Debt Ceiling (thestreet.com)

How Would a 2011 Government Shutdown Play Out? (Yahoo News)

Senate Democrats Welcome GOP Proposal to Avoid Shutdown (Los Angeles Times)