|

After nearly four years of unprecedented measures to avert a depression and revive the economy, the Federal Reserve’s job just got harder. The Fed’s policy committee meets on Aug. 9 amid revised GDP data that have raised fears of another recession. Further complicating matters, the new data suggest that the financial crisis may have greatly impaired the economy’s ability to grow, while making it more susceptible to inflation. If so, the Fed faces a daunting challenge over the next year or so amid limited policy options and little chance for help from new fiscal stimulus.

The Fed’s immediate focus will be on how serious to take the new recession worries. Wall Street is taking then very seriously, a reaction that could damage growth prospects even further. The Dow Jones industrial average plunged 512 points on Aug. 4. Broad indexes through Friday Aug. 5 are down 10 percent in only the past two weeks, which is equivalent to a roughly $2 trillion loss in household wealth. Economists at J.P. Morgan estimate that such a drop could cut into consumer spending and reduce annualized GDP growth by 0.5 percentage points in both the third and fourth quarters.

Markets breathed a short-lived sigh of relieve on Aug. 5, after the Labor Dept. said payrolls rose by a more-than-expected 117,000 in July, following upwardly revised gains of 53,000 in May and 46,000 June, while the unemployment rate edged down to 9.1 percent from 9.2 percent in June. While better than feared, those numbers offer little support for consumer spending, which rose at a mere 0.1 percent annual rate in the second quarter, the weakest quarter in two years.

The stock market losses wipe out much of the economic support from the Fed’s second round of quantitative easing. During this so-called QE2, the Fed bought some $600 in Treasury bonds through June 30 with an aim at lifting asset values generally by boosting bond prices, which lowers interest rates and makes riskier assets like stocks more attractive. Any discussion of a QE3 at the Aug. 9 meeting is sure to be heated, given that some policymakers had openly questioned QE2, fearing that it would fuel inflation and debase the dollar.

overestimated the economy’s recent strength.

The stakes are high. Policymakers are looking at a recovery that is dangerously close to stalling out. That is, growth is too weak to generate the jobs and income needed to keep it going. The GDP revisions, which go back to 2007, show that the Fed has greatly overestimated the economy’s recent strength. The new numbers show the economy has grown only 1.6 percent over the past year. “When growth slows to less than 2 percent on a year-to-year basis, the economy is simply unable to withstand a major shock or policy mistake,” says Wells Fargo economist Mark Vitner. The economy’s loss of momentum in the first half has been dramatic, with GDP growing at an annual rate of only 0.8 percent.

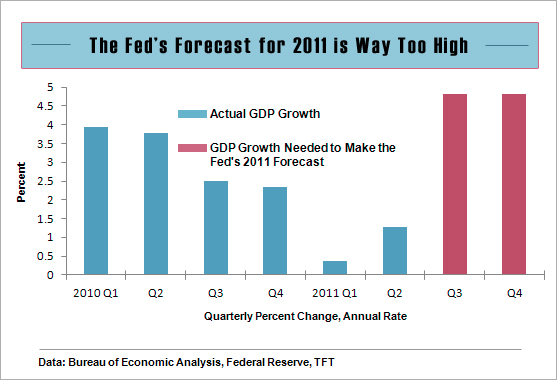

In June Fed policymakers lowered their forecasts for 2011 economic growth, from a mid-point of 3.3 percent to 2.8 percent, while also trimming their 2012 projections. It’s now clear that these forecasts are still way too high. In order to achieve 2.8 percent growth for all of 2011, the economy would have to average an annualized growth rate of 4.8 percent per quarter in the second half. Private-sector economists now expect second-half growth to average in the range of 2.0-to-2.5 percent, and most caution that the pace could be even slower—or worse.

The new GDP numbers appear to validate the notion that problems in the financial sector, weakness in housing, and issues with shaky balance sheets and burdensome debt, are more intractable than previously believed. “Some of these headwinds may be stronger and more persistent than we thought,” Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said at his June press conference. Several economists go a step further. Economists at Barclays Capital, among others, believe the GDP data and stubbornly high unemployment raise questions about the rate at which the economy is able to grow without generating inflation and whether that growth rate has shifted down in recent years.

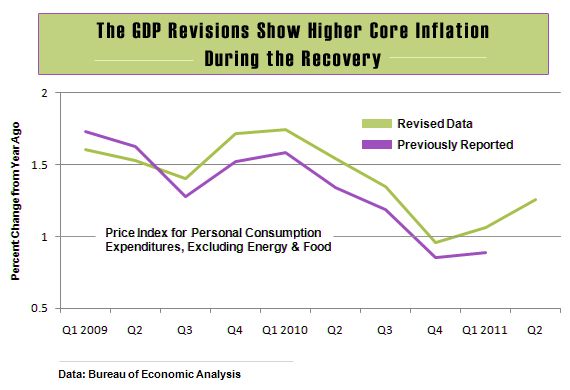

Much to the discomfort of the Fed’s inflation hawks, the GDP revisions also show that inflation is running higher than first thought, especially in recent quarters. Overall inflation, which had surged as a result of higher energy and commodity prices, is now easing lower, but inflation everywhere else is accelerating. Based on the Fed’s preferred gauge, core inflation, which excludes energy and food, is 1.3 percent measured from a year ago, but the pace this year is running progressively hotter. The quarter-by-quarter annual rate was 1.6 percent in the first quarter and up to 2.1 percent in the second quarter, a tick above the central bank’s implicit target of 2 percent.

Current inflation trends set a high bar for any significant Fed action, especially a QE3, or a third round of asset purchases. Bernanke told Congress in July that the Fed is ready to act in the face of new economic weakness, but only if inflation were falling enough to renew worries about deflation. That’s problematic, because inflation tends to lag behind turns in the economy, meaning that the economy could slide into a recession before inflation turned down.

Policymakers have other options to ease financial conditions further, should they feel new action is necessary. For one, they could be more specific about the period over which its target interest rate and level of its balance sheet would stay at their current level, instead of just saying “for an extended period.” That action would lift asset prices by reducing uncertainty about when the Fed would start tightening policy.

Also, the Fed could increase the average maturity of its $2.6 trillion in securities holdings, which would put downward pressure on long-term borrowing rates. Plus, the central bank could reduce the 0.25 percent rate it pays on deposits banks hold at the Fed. That would reduce the incentive for banks to park funds at the Fed and increase the incentive to lend them out. Economists believe the stimulus offered by any of these measures would be small, but positive. At any rate, upcoming policy decisions will be weighty. Says Wells Fargo’s Vitner, “The greater risk now is that the Fed waits too long to act.”