For elite private U.S. universities with large endowment funds, fiscal 2011 was a very good year. After suffering a 30 percent decline in its endowment in 2008, Harvard University reported last month that its fund—the largest in the country—grew by $4.4 billion to $32 billion last year, reaping the university a 21.4 percent return on its investments. The high returns have some economists, lawyers, and even some lawmakers, questioning the merits of continuing to give deep-pocketed universities tax breaks at a time when federal and state budgets are starved for revenue.

Stanford, Yale, the University of Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology also posted gains of 22 percent, 21.9 percent, 19 percent, and 17.9 percent, respectively, in the fiscal year that ended June 30. Other Ivy League schools also saw strong returns.

“At some point, a nonprofit gets so rich that it seems kind of obscene to let wealthy universities get out of paying taxes,” said James Miller, an economics professor at Smith College. “Especially with this new Super Committee, I think the federal government is going to start looking a lot harder at the revenue running out the door every year—especially to institutions like Harvard that don’t exactly need it.”

Like most non-profit organizations, universities pay no property tax, which has led to an unprecedented legal challenge in Princeton, New Jersey. According to N.J.com, the University is being sued by a group of local residents who argue that Princeton owes property taxes on nearly 20 buildings not directly related to classroom or educational activities.

fair share of taxes and thus

homeowners in the borough are

shouldering a larger burden

than they ought to be.”

Princeton lawyer Bruce Afran told N.J.com, “Activities take place in those buildings, both profit-making activities and non-educational activities, that the state legislature never intended to be tax exempt. The result is that the university is not paying its fair share of taxes and thus homeowners in the borough are shouldering a larger burden than they ought to be.”

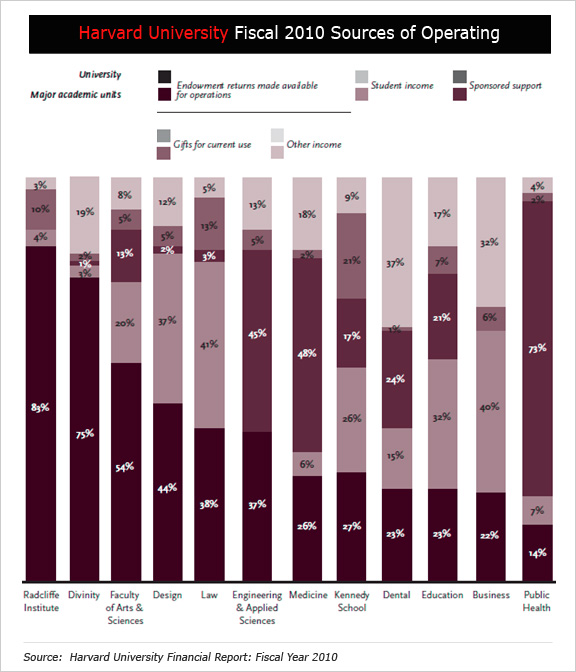

Universities like Harvard have multiple revenue streams: tuition, room and board, unrestricted alumni giving , ancillary revenue from sporting events, book sales, royalties, and other material, and, of course, the big one--the endowment. University endowment funds—supplied with capital from tax-deductible contributions —help pay for scholarships and tuition assistance, faculty salaries, upkeep of facilities, new research projects, or virtually any endeavor the university’s administration decides. But the fund can also pay a college president and other administration officials exorbitant incomes and benefits.

Yale University president Richard C. Levin made a base salary of $1,181,032, not including health care and other benefits, free housing, transportation, cleaning services, gardening, travel & entertainment expenses, and the like. Duke's head basketball coach, Michael Krzyzewski, made $3,763,373 in 2009. Of course, Duke and other universities run their athletic departments as profit centers, with revenues from television, ticket sales, clothing, and memorabilia. Massachusetts universities are awarding dozens of key administrators extravagant half-million-dollar or more pay packages, according to a report released last month by the Tellus Institute, a nonprofit research and policy organization aligned with unions.

Endowment funds are typically compromised of thousands of smaller funds established by individual donors. But once that money is donated, it is invested in a mix of stocks, bonds, private equity funds, hedge funds, and real assets at home and abroad.

As nonprofits, those investment returns are exempt from the 15 percent capital gains and dividends tax private companies, investors, and individuals pay on investment income -- so long as that income is used to further the university’s tax-exempt function, in this case education. Universities, like all nonprofits, are also exempt from paying federal corporate income taxes, and state and local sales and property taxes.

Large university endowment funds have advantages over individual and private investors, according to a 2010 Wells Fargo report. They have the benefit of holding investments indefinitely, have few liquidity constraints, and as a result, can take on more risky investments. “Larger institutions in particular benefit from access to the best managers, alternatives such as natural resource partnerships that are unavailable to individuals, and the lowest fees and trading costs,” the report said.

“These university endowment funds are the most sophisticated investors in the tax-exempt sector,” said Bruce Hopkins, an attorney for nonprofit organizations and a senior partner at Polsinelli Shugart. The larger endowments aggressive investment strategies, which include funneling money into overseas funds and domestic hedge funds “is very much the same as what a commercial enterprise does with its money, only in this case, it’s not taxed,” he said. Indeed, 82 percent of large academic institutions reported making foreign investments through their endowments. Large universities are more prone to make risky, aggressive investments because, unlike private foundations which are required to pay out 5 percent of their endowment assets each year, universities don’t have that requirement, he said.

“They [universities] should ask themselves whether offshore investments are an appropriate use of endowment funds and whether those funds would be better used by making tuition more affordable for students,” said Sen. Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, in a statement to The Fiscal Times. Grassley has accused universities of hoarding too much of their endowment funds, rather than using it to spend on scholarships and tuition assistance. “Taxpayers and students deserve to understand what they’re getting in return for the tax benefits awarded to these institutions,” he said in a January 2011 statement.

According to Hopkins, Congress could alter the law to mandate that if a university’s asset base exceeds a certain amount they have to pay income tax. “But all the members of Congress have institutions they went to and look out for, and so far, colleges and universities have just not been picked on that way.”

That’s with good reason, according to higher education advocates and lobbyists. “Nonprofit colleges, by definition, have to put revenues toward public purposes. This is different from what companies do with profits,” said Karin Johns, director of Tax Policy for the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities. “Where the private sector’s mission is to generate profits and reward their shareholders, college endowments exist to support financial aid for students, support research and advance those institutions charitable mission,” said Steven Bloom, Director of Federal Relations with the American Council on Education. “How would you tax university endowments in a way that would raise a significant amount of revenue without harming these institutions that are really a jewel in the crown of this country that generate educated students that build long-term economic growth and innovation? I don’t see how you could.”

While it’s unclear how much revenue could be recouped by taxing universities investment profits, tax- exempt treatment of all nonprofit organizations costs the federal government $30.7 billion to $95.7 billion per year, and costs states between $26.4 billion and $46.4 billion per year, Congressional Research Service economist Jane Gravelle estimated this summer. States forego anywhere between 1.5 percent and 10 percent worth of the states’ property tax collections each year because of charitable tax exemptions, which translates into higher property tax rates for homeowners and businesses, concluded a 2010 report from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

The endowments at Boston College, Boston University, Brandeis, Dartmouth College, Harvard, and MIT—which collectively own $10.6 billion in tax-exempt real estate -- would owe $235 million per year in property taxes if they were not tax-exempt, according to a 2010 study from the Tellus Institute, which studies nonprofits. These institutions do pay voluntary payments to local governments to help offset the costs of using city services and land, called Payments in Lieu of Taxes, but they only amount to about 5 percent of that $235 million, the study found.

examples of untaxed university

enterprises that deserve a second

look. “These are arguably commercial

enterprises that could be paying

income tax on profits but they don’t"

“I would love to see Congress rewrite the rules so that when you have a nonprofit organization that is clearly in the business of making money they pay income tax,” said Howard Gleckman, a resident fellow at the Tax Policy Center. “You think about the amount of dough that the academic institutions make investing, and I think there’s probably some real money there.”

All nonprofit organizations are required to pay tax on any income they earn that is deemed unrelated to their basis purpose, called the Unrelated Business Income Tax. But according to Gleckman, almost nobody pays it. He cites college athletics and bookstores as textbook examples of untaxed university enterprises that deserve a second look. “These are arguably commercial enterprises, and they could be paying income tax on profits they earn but they don’t because they’ve hired their tax-deductible lobbyist that argued for one reason or another that this particular activity is intrinsic to the entity an should be tax-exempt,” Says Gleckman.

But taxing universities is not without consequences. Increased taxes could lead universities to hike tuition or cut back on student aid, Gleckman said. And schools, like Harvard, say removing tax exemptions would erode the donor base. “If donors knew that the money they bequeathed to their alma mater would partially or fully be heading to the state, they would think twice before writing that check,” said a 2009 piece by the Harvard editorial board. They were responding to a plan Massachusetts legislators pushed to levy a 2.5 percent annual tax on the portion of college endowments exceeding $1 billion. The plan was killed.

However, according to Smith College’s Miller, universities’ argument that taxing them more heavily will increase their costs is somewhat invalid. “If universities are giving the exact reasons that would apply to a business for why they shouldn’t pay tax—that their costs will go up—then they’re arguing no enterprise should pay taxes,” he said. There’s a valid economic case for taxing wealthy, successful schools more than you do business because those institutions are not likely to close down or move locations, he said. “The worst thing that can happen when you tax a business is that they close down or leave. There’s no way Harvard, MIT, or Yale are going to leave the states they’re in, or close down and risk alienating those localities let alone the faculty, students and alumni.”