Karie Willyerd, chief learning officer for SuccessFactors, tells the story of seven millennials working at a financial services firm who asked their boss to mentor them. The boss said he didn't have time to mentor, and if they wanted that service, they would need to get it from someone else. The boss was fired. The company felt it was more important to respond to the demands of the seven rather than retain a boss who wasn't responsive. "You have to mentor them or they won't stay," Willyerd said.

RELATED: Millennials: Young, Broke, and Spending on Luxury

The situation highlights a key challenge facing human resource managers: shoring up enough trained workers as experienced boomers begin to retire in droves. "Worker productivity is one of the biggest workforce challenges we're going to have over the next five to seven years," as roughly 30 million boomers with as much as 30 years of experience leave the workforce and are replaced with those with less than 10 years experience, said Willyerd, author of The 2020 Workplace: How to Attract, Retain and Keep Tomorrow's Employees Today, particularly in the knowledge economy.

Though many boomers have postponed retirement, that's only delayed the coming experience gap. According to the Department of Labor, by 2014 there will be 49 million baby boomers ― those born between 1946 to 1964 ― in the labor force, down from roughly 59 million in 2010,while that number will be 67 million for young workers born between 1975 and 1995. Boomers are the most skilled segment of the workforce, so as they exit, that will put downward pressure on labor productivity, says Neil Dutta, an economist with Bank of America Merrill Lynch. "We have the smartest people leaving and very unskilled people coming in," he said. He said that lower productivity ultimately means lower corporate profit margins over time.

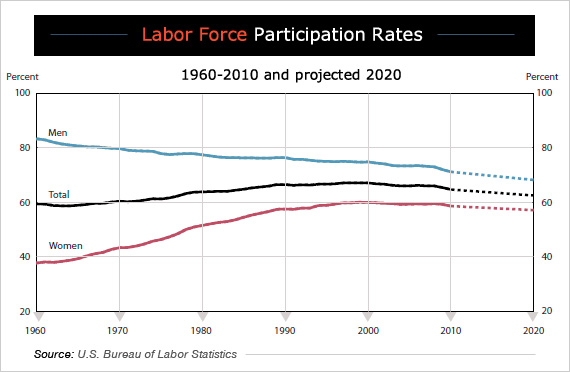

In the year 2000, there were 76 million boomers in the prime age group, ages 25 to 54, the age at which there are the highest participation rates, at 81 percent. But by 2011, that participation rate fell by half as many chose to retire and exit the workforce, dragging down the overall labor force participation rate, says Mitra Toossi, a senior economist in the Office of Employment Projections with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. She said the labor force participation rate is down drastically, from 67.1 percent in the year 2000 to 63.4 percent.

The labor department's chief economist, Adriana Kugler, says that's expected to go down even further, to 62.5 percent, by 2020. Kugler said in addition to boomers retiring, young people are staying in school longer, further impacting the labor participation rate.

In the case of general managers and leaders that drive innovation in organizations, it takes years to build that expertise. So companies "have to scramble to make up that shortfall. You can't just turn a switch and turn people into deep experts overnight," says Kim E. Ruyle, president of Inventive Talent Consulting, LLC. An April 2012 survey conducted by AARP and the Society for Human Resources Management found that 72 percent of human resource professionals polled described their organization's loss of talent due to older workers retiring as a problem.

Willyerd says that at one major defense company she works with, nearly 80 percent of the salaried staff are eligible for retirement in the next five years. Their plan is to invite the newly-retired employees back in for special projects and temp work in order to transfer their skills to the next generation. American Express has a similar program that allows boomers to transition into retirement while mentoring their replacements.

But some worry that millennials won't work as hard as their boomer predecessors. "I think there is a greater sense of entitlement in millennials," said Ruyle. He recalls interviewing a young candidate for a mid-level manager position who started laying out an extensive list of expectations, asking that the company invest in his development and advancement. He was not hired.

Millennials are also placing more emphasis on leisure and work/life balance than boomers did at the beginning of their careers, says Jean Twenge, a professor of psychology at San Diego State University and author of Generation Me. A 2010 report she co-authored found that millennials "work to live," whereas boomers "live to work."

Kevin Gavin, chief marketing officer of ShoreTel, which provides internet-based business phone and communications systems, says that the millennial lifestyle doesn't always translate into reduced productivity. He says millennials tend to "play hard," but they also work just as hard. He said his corporate culture encourages maintaining a healthy personal life. "We have no problem finding a large pool of highly motivated millennials. It's a bad rap they're getting that they're slackers."

Carl Van Horn, director of the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University, points to a May 2012 study by his group: Chasing the American Dream, Recent College Graduations and the Great Recession, that shows over 80 percent of students worked either part-time or full-time in college. This debunks the myth that these are "trust fund babies snowboarding three years after they graduate," he said.

RELATED: Exclusive Survey: The Hottest Brands Among Millennials

He points out that with the average student owing roughly $25,000 in loans when they graduate, combined with a tough job market, they're hardly in a position to take it easy. "I find with young workers, there are many more grinders than slackers, so I'm not worried about productivity." Further, he says that younger workers will be paid less than older, more experienced workers to produce the same amount of work, which will ultimately increase productivity.

Another compensating factor could be the influx of an entirely different subset of employees – skilled workers from abroad. "Immigrants will be the biggest chunk of people to replace the boomers and will account for any net growth," says Harry Holzer, a professor of public policy at Georgetown University. A U.S. policy favoring an influx of skilled immigrants ― or one that retains foreign students who attend college in the U.S. ― could make up for some of the shortfall that he predicts in key industries, like engineering, skilled construction, biotechnology and physician assistants. But he also thinks millennials in the U.S. will do their part. "I think the great recession will make them hungry for real employment," he said.