|

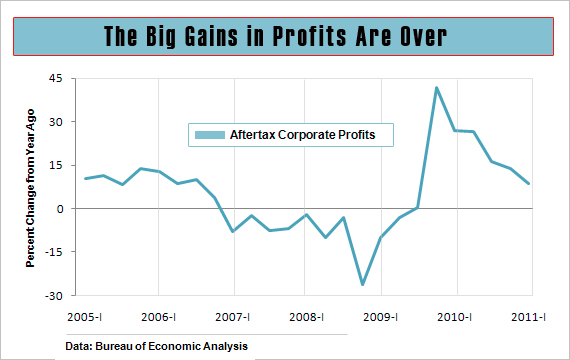

It’s earnings season. As of Friday, 143 companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index have reported second-quarter profits, and as in recent quarters the news has been generally upbeat. But while investors may be comforted by current results, it is future earnings they are starting to worry about. After a remarkable run over the past two years, profits are growing much more slowly than they had been earlier in the recovery. But it looks like companies can continue to crank out enough good news about earnings to keep investors happy.

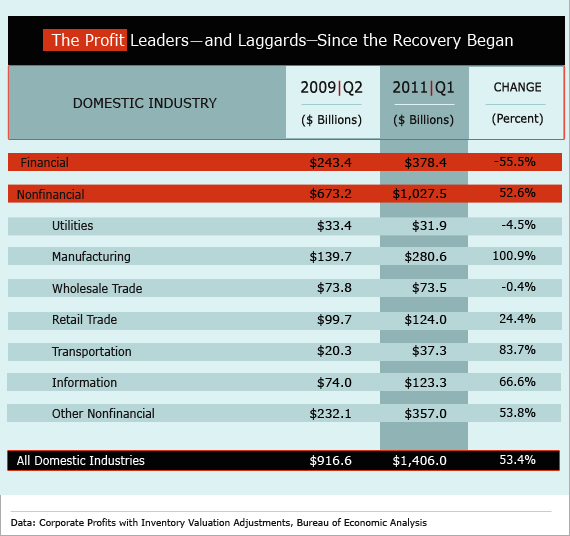

Corporate America has been a profit machine in recent months, which is remarkable given the recovery’s lackluster economic growth and a dearth of pricing power. Since the recession ended in the second quarter of 2009, earnings of domestic industries have grown 53 percent, according to the Commerce Dept.’s roundup of several thousand companies. Profits in manufacturing, which generate 20 percent of domestic earnings, have doubled, as machinery makers have seen their bottom line triple, and earnings in the computers and electronics industry are four times higher. Reflecting strong emerging markets and a weaker dollar, earnings from overseas operations are up 28 percent.

Based on a mix of actual and projected reports, S&P 500 companies are expected to post growth in second-quarter earnings per share of 9.2 percent, according to Thomson Reuters. However, excluding Bank of America, whose profits were hit hard by settlement of a lawsuit involving mortgage-backed securities, earnings are projected to grow a solid 15.2 percent. Already, 75 percent of the 143 reporting companies have beat analysts’ expectations, far above the historical average of 62 percent for any given quarter. Given still-high levels of commodity prices vs. a year ago, the materials and energy sectors are expected to lead the gainers this quarter, along with high expectations for technology and industrials.

For guidance on future earnings, it’s important to look at how companies have been able to achieve their recent gains. Expansion of profit margins has played a central role, and it will be a crucial factor in coming quarters. Margins determine how much a company earns from a given volume of sales, and can have an explosive effect on profits in a recovery. If margins double, for example, firms can earn twice as much from the same number of items sold. Since the recovery began, margins among nonfinancial corporations have expanded nearly 40 percent, even as sales have also grown. Of course one reason for the margin boost is jobs, or the lack of them.

During 2008 and 2009, private-sector businesses slashed 8.5 million workers from their payrolls, resulting in a huge two-year gain in productivity, or output per hour worked. As a result, unit labor costs, which are workers’ pay and benefits adjusted for productivity gains and which play a big role in determining profit margins, plunged by the most on record. Even though product prices were barely rising, margins surged, as unit labor costs fell.

Now in 2011, productivity has slowed sharply, as it typically does in a recovery, as businesses begin to add more workers or productivity peaks Productivity growth slid to 1.3 percent in the year through the first quarter, from 6.7 percent a year ago. Productivity gains are no longer offsetting the 2 percent or so pace of workers’ pay, which means unit labor costs are starting to creep up. For now, prices are still outpacing costs, so margins are still expanding but much more slowly.

Will rising costs put an end to the expansion in profit margins, which would intensify the downward pressure on the corporate bottom line? History suggests that, outside of a steep and prolonged slowdown in economic growth, margins should be able to hold up, even amid slower productivity growth. Economists at J.P. Morgan point out that in the recoveries of the early 1990s and early 2000s, margins continued to expand for several years, even after productivity growth cooled and costs started to rise.

In this recovery, as in those past, the path of profits will boil down to the relative strengths of inflation and the labor markets. In coming quarters, prices will most likely have the upper hand. Many businesses are already flexing a bit more pricing power, as seen in the acceleration in core inflation, which excludes energy and food. In their second-quarter earnings reports, both Coca-Cola and Pepsi announced increases in retail prices. At the same time, even though productivity has slowed, it is highly unlikely that increases in workers’ pay and benefits will speed up from their current subdued pace with the unemployment rate over 9 percent and not expected to fall rapidly. Under that scenario, unit labor costs will remain in check relative to prices, and margins will continue to expand at least gradually.

Corporate bottom lines will also get support from top-line revenue growth. Second-quarter revenues for S&P 500 companies are projected to grow 10 percent from a year ago, according to Thomson Reuters, up from 9 percent in the first quarter and 8 percent in the fourth quarter of last year. In announcing its second-quarter results, Intel reported record double-digit revenue growth. Sales growth for the S&P 500 is more than twice the pace of overall spending in the economy, implying that the recovery in the corporate sector is much stronger than the upturn in the broader economy. This is due in part to increased global demand, with exports up 8 percent.

In addition, the government sector’s drag on GDP growth resulting from a 4 percent decline in spending is masking some of the economy’s profit potential. Over the past two quarters, real GDP has grown at an annual rate of only 2.5 percent, but excluding the weakness in federal, state, and local governments—which have no direct impact on corporate profits—private-sector GDP has grown nearly 4 percent.

About the only thing that could stand in the way of continued, if slower, earnings growth is a new bout of severe weakness in the economy, possibly the result of the debt ceiling crisis. With the bulk of the cost-cutting phase of the profits recovery now over, earnings are increasingly dependent on gains in sales. Economists have downgraded their second-half forecasts for economic growth, but they still generally expect GDP growth in the range of 2.5 to 3 percent. As long as margins continue to expand, that should be sufficient to generate enough earnings growth to keep investors in good spirits.