When Ina Drew stepped down from her senior management post at JPMorgan Chase earlier this year, in the wake of revelations that a London-based trader under her supervision had lost billions of dollars through a series of trades that the bank had explicitly told his group not to undertake, she voluntarily forfeited all the compensation that the bank would have been entitled to “claw back” from her as punishment for her management failures.

Clawbacks like that were a key element of the reforms proposed in the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, and one of the easiest for everyone to agree needed to be implemented (however unpalatable they may seem). The prospect of being able to demand that a renegade banker sell his house in the Hamptons, his yacht and his Porsche in order to repay his bonuses to satisfied a kind of yearning for retribution on the part of banks’ critics.

RELATED: 5 Execs Who Should Give Back Their Bonuses

As for the banks themselves, well, it was sheer pragmatism. Agreeing to clawbacks meant that they could continue to pay lavish salaries and bonuses to those bankers and traders who generated the biggest returns for their institution, despite still-strong public ire at the spectacle of financial masters of the universe spending more on a single night’s entertainment than some on Main Street earned in three months. The optics were a lot better if they could reassure the public that guys like that could only keep their money if they did a good job.

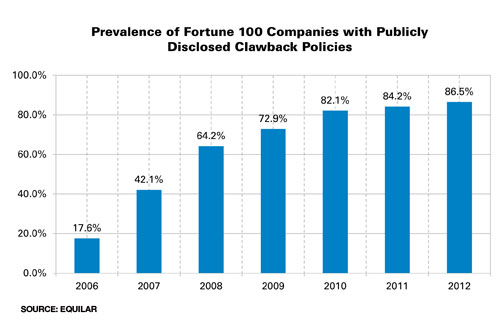

So it’s not that surprising that, as executive compensation data firm Equilar recently reported, the proportion of Fortune 100 companies with publicly disclosed clawback policies soared from only 20 percent in 2006 to 86.5 percent by 2012. It isn’t just banks enacting those policies – and the companies will be entitled to claw back salaries and bonuses in situations well beyond when employees have done irreparable damage to the business or the financial system.

As Equilar points out, while financial misconduct or ethical violations remain at the heart of the clawback idea, non-compete agreements can be backed up by clawbacks, which also can be used to promote retention.

But there’s a bigger question here, and that is whether these companies will actually pull the trigger. So far, as Equilar points out, only two big companies – JPMorgan Chase and AIG – have done so. Will companies be willing to act if public outrage isn’t there to prod them on? That clearly was the case in the “London Whale” example, as analysts and journalists began asking – almost on day one – whether CEO Jamie Dimon intended to invoke clawbacks. In other cases, CEOs may prefer to leave open the possibility of a clawback but not act.

Also of note: Other, smaller companies don’t have clawbacks yet. Has anyone knocked on Jon Corzine’s door to demand he repay anything earned from MF Global in the years before that firm’s collapse? And what will happen at Knight Capital in the wake of the computerized trading mayhem that came very close to causing the firm’s demise? Clawbacks need to be seen as consistent across an industry, and implemented fairly (don’t invoke an ethics clause simply when a top exec comes out of the closet, for instance) to be at all effective.

Finally, there’s the possibility that compensation policies might change, as top performers demand more of their compensation get paid out in “clawback proof” categories, whatever those may prove to be. Right now, few boards are likely to sign off on that kind of arrangement, but the real test will come when confidence returns to the market and everyone feels they can relax amidst the good times. It’s during such periods of overconfidence that rules and policies like clawbacks can be shuffled aside or ignored. If a company wants to recruit a top candidate, and that person’s price is that a larger percentage of his compensation isn’t safe from clawbacks, well, perhaps the company feels the risk is worth taking.

It boils down to this: Clawbacks, while welcome in many cases, are no cure-all for what ails our financial system. At best, they satisfy some kind of human need for vengeance or retribution against someone who is believed to have failed to manage risk. Like all such acts, they may make the person or institution taking revenge feel better – and publicly proclaim their virtue at the expense of the individual suffering the humiliation of the clawback – but they may not have the desired broader effects.

At least in the case of JPMorgan Chase, the prospect of a clawback didn’t serve to deter the London Whale or other employees from taking the risks that caused their ouster – and that has often been cited as the real virtue of the concept. I think we’ll have to wait a decade, or possibly two, until we can look back on a long stretch during which clawbacks have become ubiquitous throughout corporate America and be able to get a sense of whether that post-clawback world has featured fewer financial restatements and ethical crises (think WorldCom, Enron, Tyco, etc.) than in previous decades. Until then, we’ll have to take it on faith.