Well, it finally happened.

On Thursday morning the European Central Bank expanded its stimulus program to include purchases of Eurozone sovereign bonds. The program, informally labeled "quantitative easing" (or just QE) by the financial cognoscenti, has been a long time coming — for political and legal reasons — after ECB chief Mario Draghi first dangled it like a carrot on a stick in the summer of 2012.

The move was slow in coming — despite a clear slowdown in Eurozone economic growth, the rising threat of deflation and deteriorating debt dynamics in countries like Italy — because of German resistance (worries about rewarding spendthrift governments and exposing German taxpayers to default losses) and legal worries (monetary financing of debt is a no-no according to the ECB's founding documents).

Related: The Bond Market Is Warning of Huge Trouble Ahead

But Draghi navigated the legal and political quagmire to deliver on his "whatever it takes" promise to save the euro. Here are the basic details:

- Total monthly purchases will be 60 billion euros through September 2016, or possibly longer.

- Purchases will include government bonds, supra-national (such as European Investment Bank) securities, asset-backed securities and covered bonds. The last two are part of a previously announced bond buying program.

- The program will not include corporate bonds or equities (unlike the Bank of Japan).

- Purchases will have a maturity of between two and 30 years.

- Purchases will start in March.

- Purchases will have same level of seniority as private-sector buyers.

- 92 percent of the purchases will be done at the level of the national central banks, minimizing the sharing of default risk across the Eurozone (to placate German concerns).

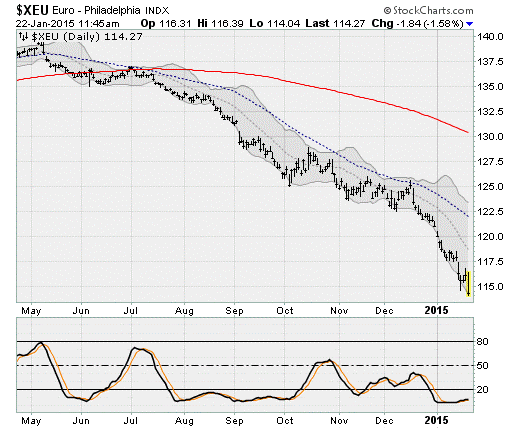

The initial market reaction has been muted. The euro, as expected, has been slammed lower by another 1.6 percent as I write this. And Eurozone bond yields have dropped hard. But equities are less than ebullient.

Currently, the Europe 350 iShares (IEV) are trading at a small loss. The Germany iShares ETF (EWG) is down 0.3 percent as it continues to struggle to break well above its 50-day moving average. And while the S&P 500 (SPX) is up 0.7 percent, shares are off their highs. Safe haven inflows are boosting gold and silver in a big way, with the iShares Silver ETF (SLV) up 1.4 percent to bring its gain to 16.6 percent on the year.

This looks like classic "sell the news" behavior.

Underlying the caution is the realization that the Eurozone isn't out of the woods yet. On Jan. 25, the Greek elections could bring the anti-bailout/anti-austerity Syriza party to power, jeopardizing Greece's participation in the new Euro-QE program and possibly its position in the Eurozone.

Related: As Global Economic Outlook Worsens, U.S. Bucks the Trend … for Now

Moreover, there are mounting questions over the potential efficacy of QE in the first place given Europe's heavy reliance on bank lending (vs. the importance of bond market financing for businesses in the United States) and the unique structural problems of the Eurozone. A continued slide into deflation and ongoing economic stalling could unleash a market rout in Europe as severe as the one three years ago.

In other words, after teasing QE for so long it's now do-or-die time for Draghi.

According to the economists at Société Générale, because of these problems the Euro-QE program needs to be triple the announced size to return inflation to the 2 percent target — something on the order of 3 trillion euros.

Why? Because in the estimation of SocGen's Michel Martinez, the European version of quantitative easing "could be five times less efficient than in the U.S." The team at Capital Economics warns that while the ECB's announcement didn't disappoint, the mixed global record of QE suggests it "won't miraculously cure all of the currency union's problems."

What would help would be a debt write-off for countries like Greece, an idea that is at the core of the Syriza party’s campaign. Turning the knife on Germany, they are calling for the same level of debt restructuring that the Germans were given in 1953 despite the still-fresh memories of Nazi horrors.

The problem, according to Martinez, is that Greece's debt load totals 317 billion euros (despite the private-sector defaults of 2012), or more than 175 percent of GDP and rising. Interest payments alone comprise 5 percent of the nation's GDP. It's just not realistic to expect the country, reeling from a 26 percent unemployment rate, to pay off this debt over time.

Related: How Plunging Oil Prices Could Create Economic Upheaval

According to the OECD, in a deflationary scenario that now threatens Europe, Greece's debt would balloon to 160 percent of GDP. There would be no escape from that.

Crunching the numbers, Martinez believes that if the Eurozone decides to take action, it could lower Greece's burden by extending bond maturities to 50 years and forgiving interest payments. That would take the debt-to-GDP ratio to a manageable 125 percent by 2022 — a level near what the IMF believes is sustainable for the country.

While Euro-QE is good news for short-term expectations, Europe has more work to do. The results of the Greek election, and the flow of economic data in the months to come, will make that clear.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: