Stocks ended last week on a high note. The Dow Jones Industrial Average crossed back over and pushed away from the 17,000 level. Precious metals have been on the move. Recent laggards in areas like industrials, energy and emerging markets are mounting an impressive comeback performance.

All has been driven by a batch of soft economic data, raising hopes that the Federal Reserve will be forced to delay its first rate hike since 2006 into the middle of 2016. Retail sales missed expectations. Industrial production and job openings were weak. We've also got the continuation of what's expected to be a soft earnings season as a strong dollar and weak commodities prices weigh on profits.

But while stocks are ebullient at the thought of the Fed's 0 percent interest rate policy continuing into its ninth calendar year, the bond market is decidedly less bubbly. In fact, the fixed income market is sending a number of warning signals that a long and powerful credit cycle is ending.

Related: Why We Might Be Headed for a Recession in 2016

A quick refresher on the dynamics in play: Years of the Fed's easy money has encouraged corporate leveraging via bond issuances, many of which were used to fund financial engineering rather than, say, real engineering on factories and machinery or the hiring of real human engineers.

Cracks are beginning to appear, with The Wall Street Journal reporting a rise in credit downgrades (vs. upgrades) as well as an increase in U.S. corporate defaults. The ratio of credit downgrades to upgrades has risen to levels not seen since the financial crisis. The problem is that the interest-coverage ratio — or how many times operating earnings can cover a company's interest expense — for highly rated firms is beginning to fall, down from 11 times to 10.3 times (a level not seen since late 2013).

The trailing 12-month U.S. default rate on lower-rated U.S. corporate bonds increased to 2.5 percent in September from 1.4 percent last July, according to Standard & Poor's.

Related: U.S. Companies Are Dying Faster Than Ever

Debt burdens have grown while operating results and asset prices, often driven by the price of commodities or the value of foreign earnings, are under pressure. According to Morgan Stanley, the ratio of debt to operating earnings for companies with an investment-grade bond rating was 2.29 in the second quarter, above the 1.91 ratio seen in June 2007 when the last credit cycle peaked.

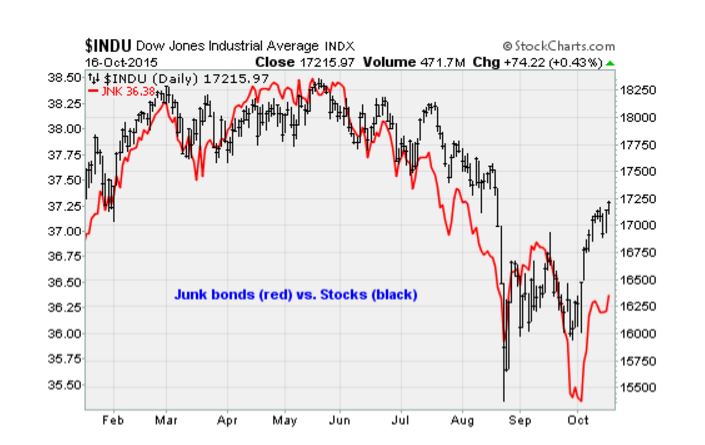

While the Dow Jones Industrial Average has rebounded nicely off of its August low, with a hairy retest in late September, "junk" bonds aren't fairing as well: As shown in the chart above in red, the Barclays High Yield Bond ETF (JNK) is badly lagging the equity rebound and remains within the confines of a scary looking five-month downtrend.

Dominoes are beginning to fall. Started in June 1998, UBS's Managed High Yield Plus mutual fund liquidated this week after trading at a growing discount to its net asset value over the past three years. Bond market trading liquidity also remains dangerously low, something institutions such as the Bank for International Settlements to the Institute of International Finance have warned about.

Related: These Simple Steps Could Prevent Another Financial Crisis

For sure, it's been a good run. In terms of longevity, the current credit cycle has now been as long as the 2003-2007 cycle driven by the Fed's low rates, mortgage securitization and consumers funding purchases out of cash-back home equity withdrawals. Yet the longer a cycle goes on, the less positive benefit cheap credit has for the economy.

In our current situation, as Bloomberg recently reported, more debt is becoming less and less beneficial to corporations. Older, high-yield debt has now mostly been replaced. Eric Beinstein, J.P. Morgan's head of high-grade strategy, warns that the "benefit of lower yields for corporate issuers is fading." Lotfi Karoui, credit strategist at Goldman Sachs, highlights the "increasingly alarming" deterioration of corporate balance sheet health.

The feeling that we're near the end of the road on all of this can be seen in the action in Wal-Mart (WMT) last week: Shares lost 11.8 percent in the three days through Friday after the company said fiscal 2016 sales would flatline and fiscal 2017 earnings per share would drop 6 percent to 12 percent despite the approval of a $20 billion share-repurchasing program worth 10 percent of the company’s market capitalization. The problem for Wal-Mart is rising wages: 75 percent of the earnings reduction is due to wage increases.

When more debt-funded stock buybacks can't juice the stock price, it's time to get worried. Historically, when Wal-Mart's share price collapsed, the broad market wasn't far behind.