Investors are nervously awaiting the start of the first-quarter earnings season today when Alcoa (AA) reports after the close. Stocks and the economy are looking vulnerable, and hopes for corporate profits are not high.

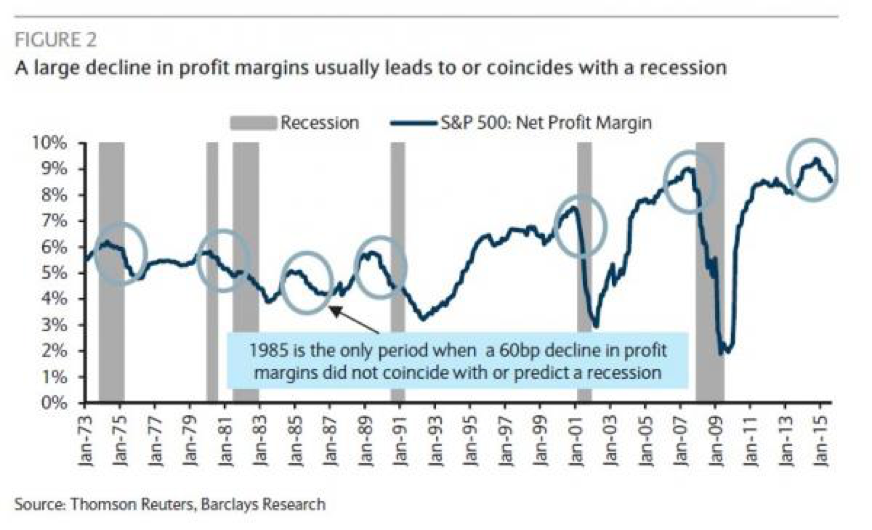

The first three months of the year look likely to be the worst quarter for earnings since 2009, with a 10.1 percent drop in S&P 500 profits expected, down from the 0.7 percent growth that was expected for the quarter back in December. The early optimism has since faded, driven largely by declines in energy sector estimates. Analysts are now bracing for the fourth consecutive quarter of falling profitability. Not only that, but Albert Edwards, global strategist at Societe Generale, warns the slump makes a new recession "virtually inevitable."

Related: What Donald Trump Gets Right About Stocks and the Economy

Others are more sanguine about the prospects of a recession. Gerard Minack, a bearish former Morgan Stanley analyst based in Sydney who now self publishes his own report, Downunder Daily, has also covered the topic lately. Yet he isn't so sure a recession looms, drawing parallels to the 1985 oil-driven profits slowdown. The difference, in his mind, is that recessions tend to require policy tightening by the Federal Reserve, which doesn’t appear imminent.

Jim O’Sullivan, chief U.S. economist at High Frequency Economics, compares the current profit recession to one in 1998, when the economy nevertheless continued to grow. “A weakening in profits related to commodity prices and the dollar is, arguably, quite different from a weakening caused by slower growth in that the drop in commodity prices and the rise in the dollar simultaneously boost real household spending power.”

O’Sullivan adds, though, that “there can still be second-round effects if the business sector is negatively affected enough to cut back on hiring, or related weakening in the equity market undermines confidence.”

Given weak earnings forecast and the recession chatter, it’s no surprise that measures of market breadth continue to narrow, with the percentage of NYSE stocks above their 50-day moving average falling below 80 percent last Thursday for the first time since early March. Fewer and fewer stocks are looking attractive to buyers at these levels. Stock valuations are also trying, with the 12-month forward price-to-earnings ratio on the S&P 500 at 16.7 vs. a five-year average of 14.4 and a 10-year average of 14.2.

Related: The Year’s Biggest Winners (and Losers) Suggest Market Trouble Ahead

For stock investors, the optimism has yet to fade thanks to dovish comments from Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, who recently talked up the downside risks to the economy and the need to be cautious about any new interest rate hikes despite a tightening labor market and surging core inflation measures.

Yet unless Yellen has found a way to fully overcome the business cycle, this confidence is likely misplaced, according to Edwards: "Recent whole economy profits data show that while the Fed plays its games, the economic cycle is withering and writhing from within. For historically, when whole economy profits fall this deeply, recession is virtually inevitable as business spending slumps."

Why is Wall Street ignoring those warning signs?

For one, being anything but a bull puts careers at risk. Better for those on the Street to be part of the groupthink, and proven wrong, than to make a brave call and stand alone if stocks rip higher. The nail that sticks out gets the hammer. The other reason, Edwards notes, is that many don't give enough credit to the role corporate profits plays in the vagaries of the business cycle.

Related: The One Data Point That Could Determine Whether This Rally Lasts

Let’s look at what's squeezing profits. Many of the catalysts are familiar and have been discussed at length in recent months: Weak oil and commodity prices, a strong U.S. dollar, global economic weakness and experiments with negative interest rates in Japan and Europe pinching bank profits.

A new dynamic in play, related to the tightening job market, has been a drop in labor productivity.

Hiring managers are having to dig deep into the pool of applicants to find new hires, which is reflected in the recent rise in labor force participation rates and a mild increase in wages. And years of forgoing investments in new technology and capital, with many CFOs instead focused on debt-funded dividend and share-buyback programs to juice stock prices, have slowed the ability of workers to increase output.

As a result, inflation-adjusted unit labor costs are rising at rates not seen since the dot-com bubble — a stark change from the post-recession lows. HR departments no longer have it all their own way. The kicker has been a decline in pricing power as U.S. consumers have largely saved, rather than spent, the windfall from lower oil prices. Producers and retailers haven't been able to raise their prices to compensate for higher labor costs. Thus, margins have been pinched.

Related: Not Even Hillary, Bernie or Donald Can Bring Back These Jobs

Edwards argues that higher interest rates "may not be a necessary condition to catalyze a recession and that a deep profits downturn is sufficient in itself."

He cites three vulnerabilities that make our current predicament different than the 1985 slump. For one, GDP growth has already effectively stalled vs. the 4 percent growth seen in 1986. Two, in 1986 the Fed cut interest rates from 8 percent to 6 percent as consumers, recovering from the early-1980s fight against inflation and 20-plus percent interest rates, were indulging in new loans and re-leveraging. Three, corporate debt-to-earnings ratios were much lower.

Keep all this in mind as the first-quarter earnings season plays out.