It's no secret that the post-crisis recovery hasn't been so great for the average American. Growth has been uneven. Job gains, while strong, have often been concentrated in areas like bars and restaurants. Wage inflation has been tepid. And yet, costs for things like health care, education and housing have soared.

Policymakers have focused, for better or worse, on driving down interest rates and boosting the price of financial assets, lifting corporate profits and the stock market to record highs in the process — but also widening the income and wealth inequality gaps.

At long last, there is evidence a turnabout is underway. Corporate profits are on track for their sixth quarterly decline, in part, as the labor market continues to tighten. The unemployment rate is below 5 percent. And there is nascent evidence wage inflation is ready to soar.

Related: Why It’s Time for the Fed to Green Light a Strong Stimulus

But here's the problem: New research suggests that with the global economy still vulnerable, the surge in wages that that middle-class Americans have been waiting for could actually threaten the recovery.

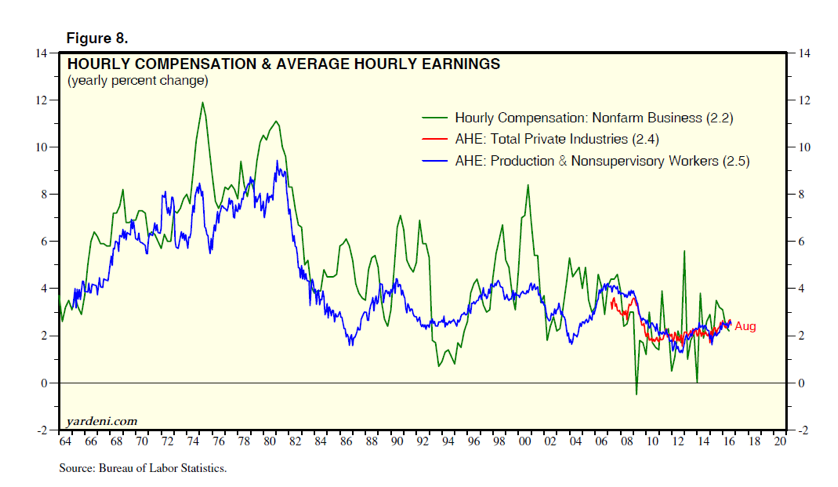

To be fair, this is still very early innings in terms of any meaningful ramp in wages. The chart below, from Yardeni Research, shows that while wage inflation has been accelerating over the last four years, the annual growth rate remains below 3 percent. Yardeni offers a few explanations for this, including high-wage Baby Boomers retiring to be replaced by low-wage Millennials, lingering fears about asking for pay raises and the headwinds from technological changes like automation, robotics and artificial intelligence.

But the trend is clearly improving.

According to Bank of America Merrill Lynch economist Michelle Meyer, wage pressure is bubbling up from the low-pay sectors such as restaurants and retailing. Some of this is being driven by state-level increases in the minimum wage. And some is being driven by a simple shortage of younger, less-educated workers. History, as shown in the chart below, suggests that high-pay and low-pay wage inflation tends to move in the same direction.

Should the trend continue, overall wage inflation should accelerate.

Related: Teacher Pay Hits Record—but Not a Good One

The prospect of that has researchers from Fitch worried about the impact on global economic growth and corporate profitability. They recently modeled a "worst-case scenario" in which wage inflation surged to a 5.5 percent annual rate by the end of 2018, which isn't outside the realm of possibility should the Federal Reserve fall behind the curve on overall inflation (a development that seems likely given the Fed’s reluctance to raise rates) and the labor market continues to tighten.

Compare this to Fitch’s baseline forecast of a 3.5 percent wage inflation rate.

The "pure wage shock" effect, holding other factors constant, would slow U.S. GDP growth to 1.1 percent in 2017 before rebounding to 2.2 percent in 2018 as higher real incomes boosts household spending. Higher wages would directly lead to higher unit labor costs for employers and thus immediate pressure on profits and overall prices as businesses try to pass higher expenses on to their customers.

This would, in turn, probably push the overall inflation rate above the Fed's 2 percent target, which could precipitate a faster-than-expected tightening of monetary policy via interest rate hikes. As a result, the Fed could push interest rates toward 3 percent by the end of next year, up from just 0.25 percent-0.50 percent now.

This would risk a financial shock, according to Fitch, as long-term interest rates surge higher around the world in sympathy with the U.S. Such a surge would risk undermining lofty valuations in a host of asset classes, from government bonds to high-yield debt and emerging market equities.

Related: Why the Stock Market Is Rooting for Hillary Clinton to Win

Under this scenario, U.S. GDP growth would slow to just 0.6 percent in 2017, dangerously near the economy's "stall speed," raising the risk of a new recession.

The takeaway: Higher pay for U.S. workers is a good thing that has been delayed far too long. But too much of a good thing could, ironically, jeopardize the recovery fueling it.