Debt-ceiling brinksmanship is back on Capitol Hill. Senate Republicans are threatening to vote against any increase to the cap unless Congress also enacts spending cuts or other reforms, potentially setting up another risky showdown this fall over the federal government’s borrowing limit.

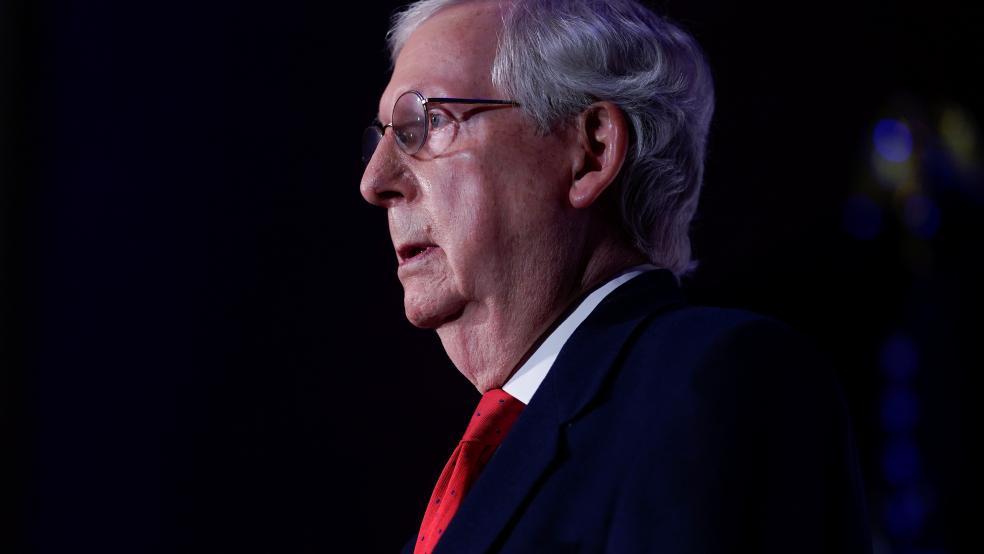

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) told Punchbowl News Tuesday night that he can’t envision any Republican voting to raise the debt ceiling and said that Democrats should address the issue in the budget reconciliation package they want to pass without GOP support.

“The new ultimatum marked a reversal for Republicans, who agreed to address the debt ceiling — the statutory amount the government can borrow to pay its bills — multiple times to advance policies under President Donald Trump that helped add $7 trillion to the federal debt during his term,” The Washington Post’s Tony Romm and Seung Min Kim note.

Democrats fume about a double standard: Democrats aren’t likely to go along with McConnell’s suggestion. “The mere prospect that it could fall on them to solve the debt ceiling conundrum left some party lawmakers seething,” Romm and Kim report, “particularly after they joined Republicans to raise and suspend the ceiling under Trump out of a belief that the issue is too dire to politicize.”

Relying on the reconciliation bill could be problematic anyway, given that it may not be ready before the debt limit runs up against a dangerous deadline.

A fall X Date: Under an agreement reached two years ago, the debt ceiling is currently suspended until the end of this month, meaning that the Treasury Department is likely to have to soon employ accounting maneuvers known as “extraordinary measures” that enable it to keep paying its bills in the absence of additional borrowing.

The Congressional Budget Office said in a report Wednesday that such measures could prevent the Treasury from running out of cash until October or November — a little later than Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen had forecast earlier this year. The budget office report said that the federal government’s cash balance of more than $850 billion as of June 30 is less than half of the $1.8 trillion it had at the beginning of the fiscal year last October but is “still very high by historical standards.”

That, combined with the extraordinary measures, should allow the Treasury to finance normal government operations into the beginning of the new fiscal year, the CBO analysis said, adding that an earlier or later date is possible. Without another increase or suspension of the borrowing limit by then, the U.S. could have to delay some payments, face a market-rattling technical default on its debt or both.

The Bipartisan Policy Center think tank estimated earlier this month that Treasury’s cash and extraordinary measures would be exhausted sometime this fall, noting that Covid-19 relief payments and the uncertain economy make such forecasts more difficult than in past cases.

We’ve seen this before: In 2011, Republicans also demanded spending cuts in exchange of a debt-limit hike, and while the showdown was ultimately resolved by an agreement with the Obama administration to cap spending, the political dysfunction on display that summer shook markets. Democrats also say that the spending restrictions enacted then undercut key federal agencies and programs, causing problems that they are now trying to correct.

Why it matters: Besides raising the specter of a default and adding costs to the government’s books by relying on extraordinary measures, the fight over the debt ceiling is also an extension of sharp differences over federal spending in general and Democrats’ planned infrastructure spending in particular. “I don’t think Republicans want to enable [Democrats] to spend trillions and trillions of dollars that we believe simply are designed to grow government,” said Sen. John Thune (R-SD), according to the Post. And Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) said it wouldn’t be responsible to raise the debt ceiling without structural reforms, adding that Democrats need to address “long-term insolvency of things like our entitlement programs.”

The numbers: Before it was suspended in 2019, the debt limit was set at $22 trillion. It will reset to the current level of national debt — $28.5 trillion as of June 30 — when the suspension ends.

The bottom line: Some Democrats believe some Republicans would go along with a stand-alone bill to again suspend the debt limit until, Punchbowl notes. But for now, the path forward is uncertain and we’re likely to see more brinksmanship before the debt ceiling question is resolved.

The Debt

Republicans Tee Up a Debt Ceiling Showdown

Reuters/Bryan Woolston