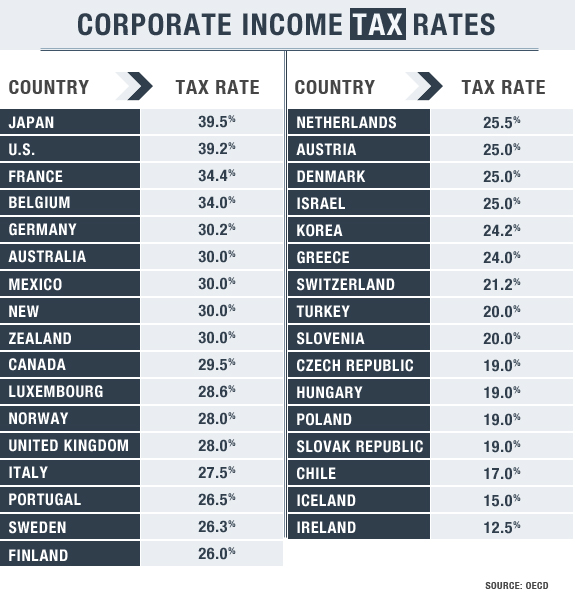

American businesses face the second highest income tax rate in the world among leading economies, and would-be reformers have been focusing relentlessly on that fact as they push for changes that would bring the rate more in line with international standards.

“A lower corporate tax rate is necessary to make the United States a more attractive location for the capital investment needed to fuel job growth,” a recent Business Roundtable report asserted.

“Without reform, it is likely that U.S. competitiveness will continue to suffer,” President Obama’s fiscal commission report declared. It recommended reducing the current 35 percent corporate tax rate to somewhere between 23 percent and 29 percent. However, the reform that business is pushing could increase the federal deficit by $1 trillion over the next decade, and open even more loopholes in the corporate tax code.

As part of an effort to change the perception that he’s anti-business, President Obama met with chief executives at the Blair House last week. Not surprisingly, the CEOs back changing the tax code, as do Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, the Democratic and Republican co-chairs, respectively, of the fiscal commission. The commission’s top staff included Treasury Department tax counsel Joshua Odintz, who will likely play a key role in formulating administration tax policy.

Last year, the administration proposed raising additional revenue by closing overseas tax loopholes. But that went nowhere. Now, after the Democrats’ November “shellacking” at the polls, Obama has promised to take on reforming the entire tax code. Top corporate lobbyists are relishing the prospect of the corporate income tax being the place to start, perhaps as soon as Obama’s budget message next month.

“It would be surprising to me to only do the corporate piece, but it would certainly be more manageable,” said Kenneth Kies, a prominent Washington corporate tax lobbyist who learned his craft while a top Republican staffer on the House Ways and Means Committee in the 1990s. “That would be a Reagan-like move to put off the really hard (individual income tax) stuff until after the election.”

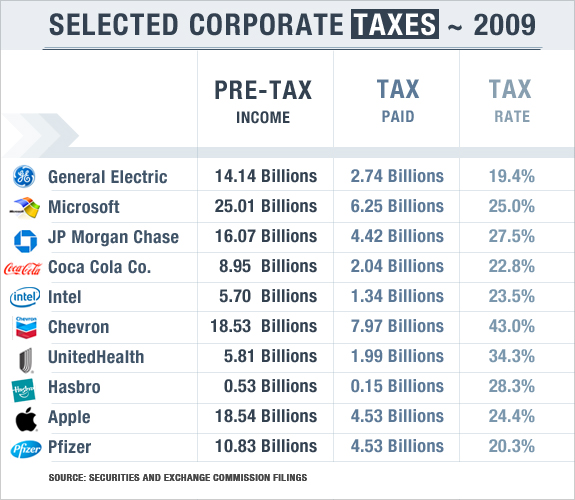

But tinkering with the corporate income tax code in the context of huge budget deficits will run smack up against the reality that U.S. business income tax as a share of total federal tax collections is at its lowest level since 1983, according to recent Treasury Department testimony on Capitol Hill. As a share of the nation’s GDP, corporate tax collections today are lower than at any time since World War II.

And corporate tax collections are headed even lower without change. During the third quarter of this year, U.S. companies generated profits at an annual pace of $1.66 trillion, which will exceed pre-recession 2007 profits by $148 billion, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Yet corporate income tax collections this year will fall to $437 billion, about $9 billion less than 2007.

Compared to the other 31 countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, U.S. taxes on corporate income in 2008 were dead last as a share of the overall economy. As a share of total government tax take, corporate taxes in the U.S. are lower than all but six countries.

The preferred vehicle for achieving lower rates is the so-called territorial tax system now used by virtually every other industrialized nation, which excludes from taxation any corporate income earned abroad. But if put in place, U.S. business taxes would plunge by as much as $100 billion a year, according to a recent Congressional Research Service report. Moreover, the gaming that has eviscerated the current corporate income tax system would grow worse, tax experts say.

“The bottom line with territorial is that it will make every tax administration problem we have now worse and knock out what remaining revenue we get from taxing foreign [corporate] income,” said Lee Sheppard, a tax lawyer for the nonprofit Tax Analysts, which publishes Tax Notes.

The U.S. corporate income tax rate is second only to that of Japan. Alone among major countries, the U.S. uses a worldwide system for assessing taxes on multinational companies. But the tax code postpones taxing on income earned abroad until it is brought back to the U.S.

That has led to a booming business for tax consultants and tax lawyers who create tax dodges for companies with major overseas operations. The shelters usually involve sham transactions that shift income abroad, and often involve transfers of intellectual property rights at firms with very low costs for producing their goods, such as software and pharmaceutical firms.

The most recent poster child for corporate tax gamesmanship involves Google Inc., which sharply lowered its foreign and domestic taxes by transferring most of its income earned outside the United States to an Ireland subsidiary, which in turn funneled it through the Netherlands to Bermuda, according to a Bloomberg investigation. The scheme, approved by the Internal Revenue Service, involved transferring a portion of the intellectual property rights for Google search software to the Irish subsidiary, even though its development began at Stanford University and was partially underwritten by the U.S. government. The daisy chain of transfers eventually moved the non-U.S. taxed income to a tax haven where the effective rate was less than 3 percent.

“It is difficult to figure out where intellectual property is being done and what it is worth, making it a lot spongier than machinery,” said Alan Auerbach, a professor of economics and law at the University of California at Berkeley. “Those kind of issues militate against the territorial system (although) corporations prefer it because it lowers their taxes.

Are there alternatives to territorial taxation to level the international playing field on tax rates? The U.S. could substantially lower rates by doing away with deferral of overseas income entirely and substituting a credit for any taxes paid to foreign governments. A tax on the global income of U.S.-based multinationals that sought only to raise the same amount of money as is raised now would require a rate about one-third lower than the current rate and it would be easier to administer, experts say. A rate of around 29 percent on global income – well within international norms – would raise additional revenue to help close the deficit.

“The better system would be a low rate on all of worldwide income,” said Edward Kleinbard, former chief of staff to the Joint Tax Committee who is now a law professor at the University of Southern California. “The technical issues of transfer pricing and what U.S. expenses should be when calculating foreign income (from moving to a territorial system) are basically insurmountable. I arrive at worldwide tax consolidation both for principled reasons and for practical reasons.”

However, “getting rid of deferral would be disastrous,” said James Hines, a tax professor at the University of Michigan law school. “No other country in the world does that. Foreign operations of American companies would eventually be sold off to other companies domiciled elsewhere.”

Are there alternatives? Berkeley’s Auerbach, who predicts shifting to a territorial system will lead to a “race to the bottom” as countries compete to lower rates, recently authored a proposal for the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution that would reform the corporate income tax by only levying it where products are sold, not produced.

He would simultaneously replace the current depreciation schedule for capital investments with an immediate deduction for investment costs. That part of the proposal, at least, was endorsed by Republicans and Democrats as a temporary measure in the recently enacted tax bill.

“The plan delivers a host of economic advantages to U.S. businesses and American workers by promoting domestic corporate activity and encouraging investment,” he wrote. “Importantly, this reform would achieve these benefits without reducing corporate tax revenue.”