State pension programs across the country have undergone a major transformation, as more and more of them are cutting back the amount of money they set aside for retired workers, gambling that they can meet their obligations through investments instead of savings, according to a review by The Fiscal Times of the latest funding data.

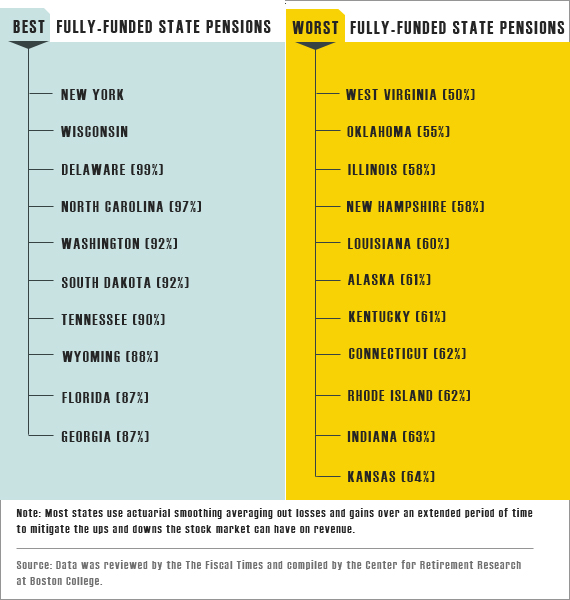

A decade ago, slightly more than half the states in the U.S. had fully funded pension programs, but today only New York and Wisconsin can make that claim. Though the Great Recession has battered and drained most state budgets, New York and Wisconsin stand alone because they have kept up with their annual funding requirements in both good times and bad. (Fully funded pensions are mandated in New York; they are not mandated in Wisconsin.)

The burgeoning cost of retirement programs has become a critical factor as states across the country struggle to balance their budgets. No longer able to count on dependable and substantial returns on their investments, many states are raiding their pension funds to meet obligations to retired workers, leaving them vulnerable to another financial crisis. According to 2009 data from Boston College’s public plans database (which contains the most recent data available), state public-employee pension programs are underfunded by a total of $708 billion. (Numbers from the Pew Center on the States are slightly different, as they’re based on 2008 data; they estimate that the U.S. state pension system is underfunded by $452 billion.)

New York has the second largest pension fund in the country behind California, boasting more than $237 million in assets and covering nearly 1.5 million retired and active workers as of 2009. Wisconsin has the nation’s 9th largest public pension fund, with nearly $79 million in assets as of 2009, covering roughly 560,000 people.

“The most important factor in a plan’s funding is if they consistently make their annual contribution,” said Jean-Pierre Aubry, a research associate at Boston College, who helped collect the data. “It sounds simple. You put enough money in your savings account, you’re going to have a bigger balance. But that’s really the driving factor in the funding.”

Kil Huh, director of research at the Pew Center on the States, noted, “These [top] states have been exhibiting the financial discipline in order to pay those annual bills year over year.”

Most state and local governments provide a defined-benefit pension plan for public employees as part of overall compensation. Public-sector pensions are financed through a combination of employee and employer contributions and investment earnings. The average state employer contribution rate was roughly 10 percent of employee salary, as of 2009, while the average employee contribution rate was roughly 5 percent, according to Boston College’s database.

New York is fully funding its state pension program even as Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo attempts to eliminate a $10 billion budget deficit by slashing overall spending and laying off up to 9,800 employees. While Wisconsin has one of the most solid state pension programs in the country, embattled GOP Gov. Scott Walker has stripped public employees of most collective bargaining rights and is seeking to require public workers to pay substantially more for their pensions and other benefits to address the state’s $3.6 billion deficit.

How well these and other states fare in coping with their financial crises could have a profound bearing on the future of their pension programs.

“The plan that’s 90 percent funded could in reality be in worse shape than the plan that’s 75 percent funded, based on the fiscal condition of the plan’s sponsor,” said Keith Brainard, research director at the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA). “If you’re in a state that’s doing poorly fiscally, even if your pension plan is in great shape – if you can’t afford to fund it next year, that’s a big problem.”

Public Workers to Pick Up Tab?

It’s clear that tough choices will have to be made, and public workers could very well be left picking up some of the tab. Recent retirees and those soon to leave the workforce are less likely than mid-career and new public workers to see a reduction in benefits, according to some experts. But a secure retirement is becoming further out of reach as the economy forces more states to ask for more, and provide less in return.

Fifteen states passed some type of reform in 2009 to help deal with post-employment benefits. Those reforms largely fell into five categories, according to a report from the Pew Center on the States: keeping up with funding requirements; reducing benefits or increasing the retirement age; sharing the risk with employees; increasing employee contributions; and improving governance and investment oversight.

The average funding ratio for all 50 states is 79.1 percent, a number expected to drop by 2 or 3 percentage points when the new 2010 numbers are released in April, experts say. “The biggest driver is market performance, and of course the last 10 years the market performance has been cruddy,” said Brainard of NASRA. “The idea is that the unfunded liabilities are paid off like a mortgage would be over time. If the markets behave roughly like we expect them to, that unfunded liability would decline steadily over the next 20 or 30 years.”

Some states are taking a range of steps to rein in the cost of their pension programs. Colorado, Minnesota and South Dakota, for example, reduced their benefits for existing retired plan members last year – a measure that demonstrates that that no current or past public worker is exempt from a state’s fiscal challenges. Additionally, in 2008 and 2009, 17 states reduced future benefits or increased employee contributions. Missouri increased the retirement age to 67 for new employees to receive full benefits, joining Illinois as the state with the highest retirement age in the nation.

Illinois, which is struggling with a massive deficit, hasn’t made any contributions to its pension system recently, but paid full benefits last year by drawing down its pension funds by roughly 10 percent.

“Needless to say, that’s not something you can do in the long run,” said David John, a senior research fellow in retirement security and financial institutions at the Heritage Foundation. “For the most part, what you’re looking at is the question of what will happen 10 or 12 years from now, or maybe more.”

Determining the outlook for most retirees will take time, depending on state law, future legislative decisions, and the performance of the markets. But given the volatility of the markets and the economy the past several years, John says there’s no avoiding making the difficult choices some states are now starting to make. Whether it’s a combination of increasing the contributions workers make, changing the benefit structure, or changing the formula of cost of living increases, the state pension system 10 years from now won’t look anything like it does today, experts say.

Related Stories:

The Truth About the State Pension Crisis; Separating economic myth from economic fact (Hawaii Reporter)

States scaling back public pension plans to close funding gap (The Washington Post)

State and City Pensions Could Destroy U.S. Economy (The Fiscal Times)