With President Obama’s re-election, the major provisions of the Affordable Care Act are moving forward – including implementation of a new 2.3 percent excise tax on medical device sales starting on Jan. 1. The tax is expected to raise some $30 billion over the next decade, though some device makers are still lobbying Congress to delay implementation as part of a deal to avert the so-called fiscal cliff. More than 800 companies and organizations sent a letter to congressional leaders after the election asking that the tax be repealed.

Gary Guthart, CEO of robotic surgery leader Intuitive Surgical (ISRG) of Sunnyvale, Calif., wasn’t among those to sign the letter, and says he isn’t concerned about the new tax’s impact on his business: With revenues of $538 million in the most recent quarter – up 20 percent year over year – and net income up 50 percent to $183 million, he’s confident Intuitive can absorb the tax. But Guthart is concerned about how health reform will impact innovation in the medical device industry, as political leaders and insurers become more vigilant in weighing the costs of expensive medical procedures against the benefits. “Questions of cost effectiveness and clinical effectiveness must be balanced with enough time and incentives for innovators and entrepreneurs to try to new things,” he told The Fiscal Times.

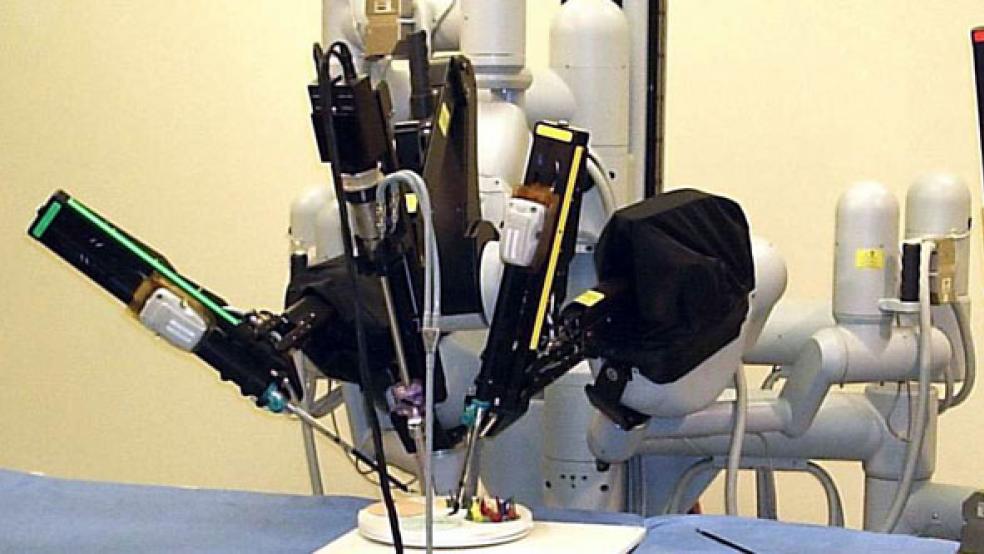

An engineering Ph.D. and a 16-year veteran of Intuitive, Guthart is a leading voice in the devices industry because of da Vinci, the company’s sophisticated line of robotic instruments that allow surgeons to perform complicated procedures while making a few tiny incisions. Intuitive’s rapid growth has made it a Wall Street favorite: In the last year its stock has shot up more than 29 percent, to $537.50 a share.

Guthart spoke about the future of robotic surgery and the role policymakers should take in preserving innovation. Edited excerpts follow:

The Fiscal Times (TFT): How will the new medical device tax impact your business and the broader industry?

Gary Guthart (GG): We’ll pay it and move on. It puts some constraints on future investment, but we have the financial flexibility to adjust. But for smaller companies just starting, the implications are more dire. It’s a tax on revenue – not a tax on earnings – so that can delay profitability for companies trying to transition from being an innovative startup to a profitable ongoing concern. It can also dissuade investment away from health care and into other things, because it takes longer to get a return. We’ll have fewer startups looking at health care and more startups looking at social media.

TFT: So what do you want the government to do for your business?

GG: We need rational legislation and regulation when it comes to innovation. Innovation is not done on a whiteboard in a perfectly linear path. It requires an interaction between the medical, technology and financial communities. There has to be room for that cycle to occur. If it’s constrained because either the barriers to regulatory approval or the barriers to reimbursement are set so high, I think you’ll wind up driving that innovation off-shore.

TFT: In a recent earnings call, you cited a decline in prostate surgeries – one of your biggest markets – due to recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force that patients with early-stage prostate cancer be treated with less invasive regimens than surgery. Do you expect the government’s role to keep evolving with the implementation of health care reform?

GG: There are fair questions being asked within the health policy community – things like: How effective is a treatment in terms of curing an underlying disease? How invasive is the treatment, and how likely is it to cause significant complications or quality-of-life problems? And what’s the cost? These questions should be understood and analyzed. But people take shortcuts at times and those shortcuts can really harm patient care. We have to look at quality of life and at people’s ability to return to productive engagement, whether it’s in returning to work or simply to full function.

TFT: But questions remain about the long-term benefits of robotic surgery to patients. How can we answer those questions?

GG: People get tripped up when they look at the acute cost – the cost of the intervention itself – but not the downstream effects of the treatment or the lifetime care of that patient. Take kidney cancer. The differences in cost are pretty straightforward: Relative to open surgery or laparoscopy, robotic surgery will have a higher up-front cost. But the return on investment comes in how long a patient has to stay in the hospital, and what the likely complications are in terms of infections, medication, and readmission.

TFT: With all the uncertainties created by health reform, does the device industry worry about investment in new technology?

GG: Up-front costs are easy to calculate, but [long-term] savings take time to understand well. Honestly, I think there’s a danger. If new techniques and technologies are not given time to evolve, they’ll be discarded before their true value is really known. It’s fair to ask the cost question, but from the point of view of policymaking, you also better leave some room for understanding an evolution of products before you make a final determination about long-term downstream value.

TFT: How would this directly affect your company? Give us an example of one of your innovations that took time to evolve.

GG: As a surgery company, we think about how we can give a surgeon the best view of diseased tissue. So we went from 2D to 3D vision. We increased visual acuity and improved the ability to see in color. We don’t do huge market-size analyses or big ROI analyses. We start deeply with the question of what is going to make a difference in a substantive way. Then we collaborate closely with surgeons, who will find opportunities we never envisioned.

Recently we introduced a fluorescent imaging system called Firefly, allowing for the real-time imaging of structures – kind of like Superman vision for things that can’t be seen with white light. A group of surgeons want to use it to identify lymph nodes that drain tumor sites, so they can easily remove them. This may cut the amount of time and tissue manipulation required to find that lymph node. That [usage] is not yet FDA-approved, but there’s a study going on in that. That’s not something we anticipated when we started the Firefly project.

TFT: You say cost-benefit analysis in health care should be done through four different lenses: patient, payer, society, and hospital. Explain.

GG: From the patient’s point of view, robotic surgery typically does not cost any more. It’s usually a covered benefit. Then the question is: Did you cure me and what were the side effects? What’s the impact on my earnings power or the economic cost of caring for myself? Robotic surgery has done really well there.

In terms of the payer, we have never gone and asked for additional reimbursement [from insurers]. Recently two former heads of CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] proposed that the best way to introduce new technologies was to provide existing reimbursement for old technologies, unless a superior cost benefit over time can be proven. We agree with that. We’ve never suggested [insurers] should pay any more for an intervention that’s done robotically. So payers have been net beneficiaries.

With society in general, it comes down to the employer and the family members of the patients once they’re out of the hospital. If complications are lower and the return to full function is faster, they’re net beneficiaries.

The only group that requires a spreadsheet and green eye shades to understand this deeply are the hospital providers: They have to do the capital investment; they have to buy the consumables. That’s the up-front investment. The benefits are reduced length of stay and reduced complications.