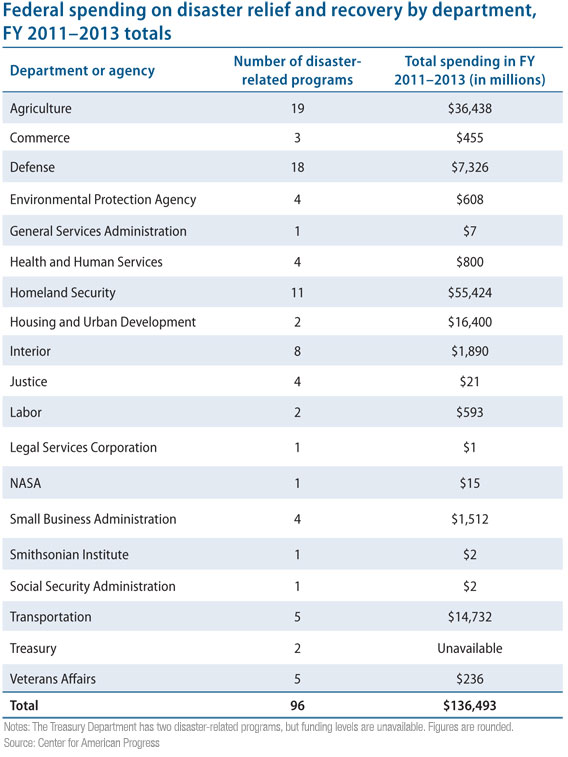

The government’s disaster-relief spending is itself something of a disaster. Six months after Superstorm Sandy ripped through New York, New Jersey and other Eastern seaboard states, a new analysis from the Center for American Progress finds that the federal government spent $136 billion on disaster relief from fiscal 2011 to 2013. That works out to nearly $400 per household each year.

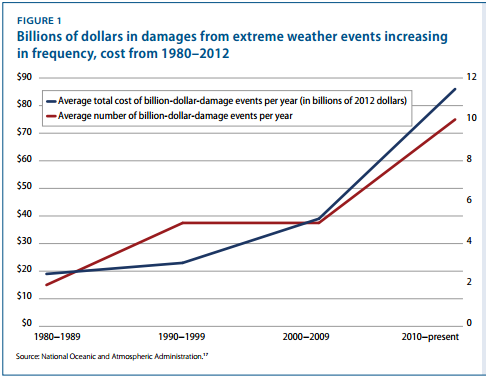

Sandy drove up the total considerably, but the U.S. also suffered through 24 other floods, storms, droughts, heat waves and wildfires in 2011 and 2012 that caused more than $1 billion in damages each, according to the report. “Combined, these extreme weather events were responsible for 1,107 fatalities and up to $188 billion in economic damages,” the report says.

Just as troubling, government agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Office of Management and Budget have failed to keep comprehensive tabs on the total levels of disaster-relief spending, the CAP report found, making it harder to properly budget for such spending.

“We need to have the federal government do a more accurate assessment of how much money the federal government actually spends on disaster relief and recovery,” says Daniel J. Weiss, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and a co-author of the new report. “We’re spending all this money on disaster relief and recovery and we’re not keeping track of it. That’s not good budgeting, and it’s bad for future planning because it means our future appropriations will have fewer dollars than are needed to have Americans cope with extreme weather.”

Most disaster-relief spending – like the $60 billion Superstorm Sandy aid package approved in January – comes as the result of emergency supplemental bills authorizing outlays beyond those set by the standard budget and appropriations process. Those emergency spending measures, which traditionally passed with bipartisan support, have faced more resistance in the past couple of years as deficit hawks sought to offset the new spending with other cuts.

The most recent federal effort to estimate disaster-related costs came in 2011, according to the report. As part of the Budget Control Act of 2011, OMB under then-director Jack Lew was required to look at the previous 10 years of disaster spending. In coming up with the average annual funding for disaster relief, though, OMB’s process called for throwing out the highest and lowest annual totals, including the $37 billion spent in 2005 because of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. The OMB averages came to $11.5 billion for the ten years to fiscal 2011 and $11.3 billion for the years to fiscal 2012.

“We believe that OMB’s estimates for 2001 to 2011 did not fully account for all federal disaster spending and that these estimates are less than actual spending because OMB could have omitted some important relief and recovery programs and agencies,” the CAP report says.

While OMB’s estimates included spending from 26 agencies and programs in 11 federal departments, CAP found 96 agencies or programs across 19 departments that had spent money on disaster assistance.

For fiscal 2011 alone, OMB found that the federal government spent $2.5 billion on disasters. The CAP report identified $21.4 billion that year, including almost $11 billion in federal crop insurance due to the drought that year that wasn’t included in the OMB tally. OMB did not immediately respond to an emailed request for comment.

CAP also says its calculations still include some holes where it couldn’t determine how much was spent, such as for the disaster-related Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or emergency food stamps, run by the Department of Agriculture. On the other hand, some of the programs included in the Cap analysis might also cover other purposes beyond disaster relief and recovery. “This is an estimate by two outsiders using available information,” Weiss says. “Let’s get the Government Accountability Office or the Congressional Research Service – a research arm of the government – to really understand this in a way that ours begins to do but doesn’t fully accomplish.”

The liberal think tank warns that the federal tab will keep growing. Billion-dollar weather-related disasters have become increasingly common, even adjusting for inflation, over the past three decades, thanks to climate change and U.S. population patterns. In a report published last week in the journal Nature Geoscience, a consortium of scientists concluded that the Earth’s climate warmed more from 1971 to 2000 than at any other time in nearly 1,400 years.

“As climate change accelerates, so will federal spending on disaster relief and recovery, which will ultimately be paid for by taxpayers,” the CAP report says. “Since additional federal recovery assistance is rarely offset by budget cuts or revenue increases, this aid will likely add to the federal budget deficit. This means that the $60 billion appropriated for recovery from Superstorm Sandy could be a harbinger of future federal spending.”