The recent rebound in the price of crude oil — up some 40 percent from the March low — dragged energy stocks higher through the beginning of the month. This, in turn, has powered a rebound in inflation expectations in the fixed-income market, punishing long-term Treasury bond prices and pushing up yields.

As a result, the deflationary danger that many worried about earlier this year seems to have passed. Gasoline is back over $4 a gallon again in California. Corporate earnings look set to rebound. Just like that, all is right in the world again. Whew.

But doubts are growing about the sustainability of the oil rally given still high inventory levels, high U.S. production, and now, reports that the Saudis are ramping up production in a belief they've "won" the showdown with high-cost American shale drillers. (The data suggest otherwise, with production out of the Bakken shale in North Dakota rising in March for the first time this year.)

Related: Oil Could Drop to $45 by October

Analysts at Barclays Capital recently warned clients that the "huge disconnect" between futures market pricing (where everything looks great) and the physical market (where indicators are signaling oversupply) cannot last. Some of the stronger U.S. shale producers have said that at current prices, they are set for double-digit production growth. Goldman Sachs analysts note that oil's rally will ultimately be self-defeating.

Barclays believes that without a rapid improvement in the supply vs. demand fundamentals, current pricing cannot be sustained. They list three reasons to be cautious about this happening: China’s economy still looks fragile, oil supply still exceeds consumption and the oil price recovery may encourage more U.S.-based producers to restart drilling operations.

Goldman believes that some of the buying that came into oil futures was driven by pair trades playing the relative cheapness of crude against the shares of exploration and production companies. Now, the valuation gap has closed, oil stocks are trading at stretched multiples and oil is trading at a premium to its own still-shaky fundamentals.

Goldman’s analysts are looking for crude price weakness in the near-term. The decline is likely to be magnified by the fact that oil speculators are as net long as they were when oil traded near $100 a barrel.

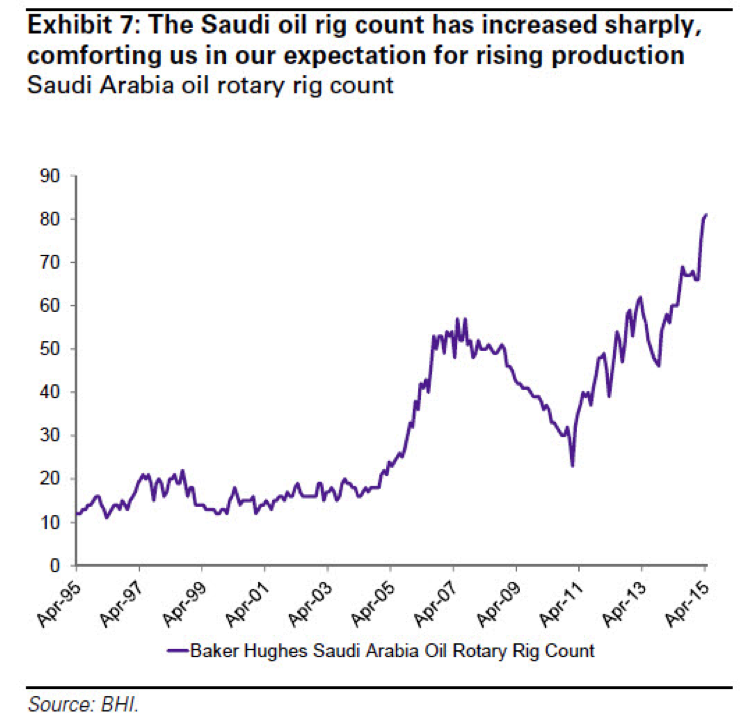

With U.S. production relatively stable, the Goldman team worries about the massive ramp up in Saudi drilling rig counts shown above. To me, it looks like Riyadh is doubling down on its strategy to force a consolidation of the U.S. shale industry by pushing prices back towards their lows. To do this, the Saudis need to flood the market when enough cheap oil to top out storage capacities.

According to Citigroup analysts, stocks in Cushing, Oklahoma — the location of oil futures delivery — are only about 10 million barrels away from the working storage capacity of roughly 70 million barrels. Spare capacity could be tested this autumn, in their view, as the surge of demand from the summer driving season ends and refineries shut down for seasonal maintenance that is likely to be deeper and longer than typical, given short shutdown cycles this winter and spring.

Related: Fracking Has Made Oklahoma the Earthquake Capital of the U.S.

If tanks top out, oil could very well push to fresh lows — complicating the Federal Reserve's planned interest rate hikes, further pulling down corporate earnings and continuing the drag on GDP growth via capital expenditure cuts.

No surprise then that equity traders are already moving. The Energy Select SPDR (XLE) is testing below its 50-day moving average for the first time since early April as key blue-chip stocks in the sector melt lower.

Yet the consensus, for now, seems to be that oil remains range-bound somewhere between $55 and $75 a barrel. There are many justifications for this as well. Oil analyst Phil Verleger, cited in a Reuters story last week, put forward the theory that Energy Information Administration (EIA) data was likely overestimating total U.S. oil production by 1.6 million barrels per day. This could explain why while U.S. production keeps rising, global inventories aren't rising as fast as many expected.

Related: Why a New Age of Nuclear Energy Is About to Dawn

Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research posits that it's also possible that global oil demand has bounced back more strongly than expected and that developing countries like China are stockpiling more oil. He also notes that petroleum inventories have been drifting lower (as is normal this time of year) and that railcar loadings (a proxy for U.S. production) have dropped noticeably over the last few weeks.

Still, he admits that the ratio of global oil demand to global oil supply — based on 12-month averages — continued to fall in April for the 14th month in a row to the lowest level since October 1998, a time when crude oil traded down near $15 a barrel and a gallon of regular gasoline cost about $1.

While we probably won't see those levels ever again, with the Saudis preparing to open the spigots, energy prices at the very least seem poised to retest the lows set earlier this year.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times: