It was like someone flipped a switch. Wednesday’s report that OPEC officials had agreed, in principle, to their first output cut in eight years sent crude prices surging 5.3 percent to $47.05 a barrel, their best one-day gain since April. Energy stocks gained 4.3 percent, with Exxon Mobil (XOM) up 4.4 percent.

Then everything flipped again. The price of crude slipped Thursday morning before climbing back above $48, swayed by uncertainty about just what the OPEC news might mean.

Related: Why the Spike in Oil Prices Won’t Hurt the Economy – or Influence the Election

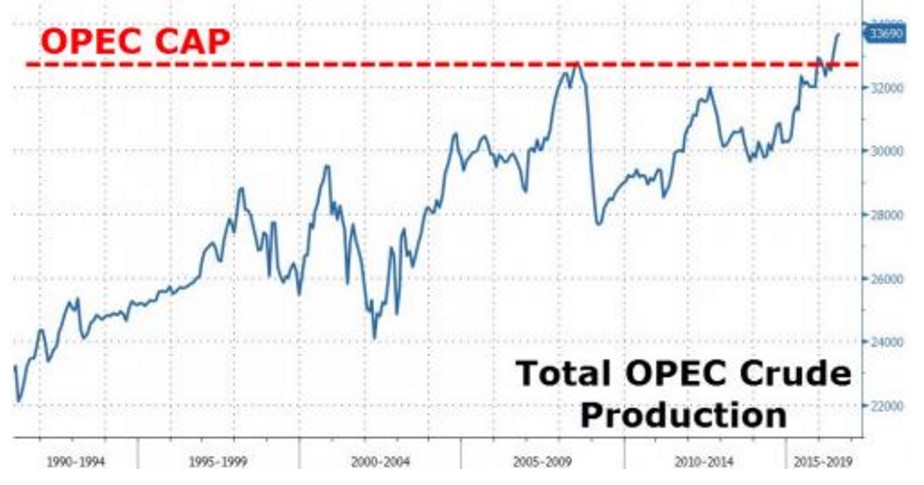

The agreement in principle would see OPEC cut output by between 200,000 and 700,000 barrels per day from the 33.2 million pumped in August. Details or action aren't expected until the next official meeting in November, but the headlines alone generated an outsized reaction from investors who have been teased with an output freeze by OPEC since February. If the agreement actually comes to fruition, it would be a huge step toward bringing the oversupplied global energy market back into balance.

But I think this is ultimately wishful thinking for a number of reasons.

Most critically, the rough agreement hammered out in Algiers this week — and only after Saudi Arabia got the intractable Iranians to the table by pledging an outright output cut to accommodate Tehran's desire to produce at pre-sanctions levels — will give way to a committee that will decide on new oil supply levels for each member country.

Moreover, OPEC is hoping to take this rough agreement to non-OPEC countries (read: Russia) in the hopes they will participate as well.

Related: Will the Nasdaq Surge End in Another Tech Wreck?

The problem is classic zero-sum game theory: If Iran or Russia can encourage Saudi Arabia to cut unilaterally, they will be better off thanks to increased revenue and increased market share. Add in a simmering regional power struggle, a religious schism and restive local populations, and it's hard to see an agreement coming together in good faith.

That’s especially true given that Riyadh appears desperate here. Its currency looks set for a devaluation amid volatility in its stock market fueled by the U.S. Congress’ override of President Obama's veto on a bill to allow the 9/11 families to sue Saudi Arabia. The new law is expected to delay the kingdom's first-ever international bond sale (as lower oil revenues squeeze the fiscal budget). The Saudi Tadawul Stock Index traded to eight-month lows on Wednesday morning, nearing its post-2009 lows.

Sure enough, just hours after the rough deal was announced and long before any serious discussions on how production cuts would be allocated, the bickering had begun: Iraq's oil minister rejected the third-party data OPEC was using to estimate their production levels.

It's also hard to see OPEC actually committing to lowering production when this in effect represents ceding the hard-fought market share gains earned from U.S. shale producers since the price war started in 2014. OPEC production has never been higher while U.S. production is down about a million barrels per day, dropping back to 2014 levels from a high of around 9.6 million. (Russian output is pushing toward post-Soviet highs as well.)

Related: Iraq's OPEC Revolt Shows Saudi-Iran Oil Deal Fragility

U.S. drilling rig counts have been slashed, down 75 percent to levels last seen during the 1999 oil wipeout when a gallon of unleaded cost less than a dollar. It's easy to imagine U.S. oil men, under their own financial pressure to service debt obligations, eagerly putting idled rigs back to work on capped wells should energy prices mount a sustained recovery.

On top of all that, the proposed cuts wouldn’t do much to bring global supply and demand into immediate alignment. No wonder Goldman Sachs commodities analyst Damien Courvalin wrote to clients earlier this week that any OPEC deal won't be enough to stop oil prices from falling. Not only was Saudi production set to decline into the end of the year based on seasonal trends but Goldman's updated supply-demand forecast pointed to a renewed build of already swollen inventories in the fourth quarter.

As a result, Courvalin is looking for oil prices to fall from $47 now to $43 a barrel by the end of the year (vs. a forecast for $51 a barrel previously). So while an OPEC deal could "support prices in the short term," assuming its finalized in November, he finds "the potential for fewer [production] disruptions and the relatively high speculative net long positioning instead leave risks to our forecast squarely skewed to the downside."

It's also hard to see OPEC actually committing to lowering production when this in effect represents ceding the hard-fought market share gains earned from U.S. shale producers since the price war started in 2014. OPEC production has never been higher while U.S. production is down about a million barrels per day, dropping back to 2014 levels from a high of around 9.6 million. (Russian output is pushing toward post-Soviet highs as well.)

Related: Iraq's OPEC Revolt Shows Saudi-Iran Oil Deal Fragility

U.S. drilling rig counts have been slashed, down 75 percent to levels last seen during the 1999 oil wipeout when a gallon of unleaded cost less than a dollar. It's easy to imagine U.S. oil men, under their own financial pressure to service debt obligations, eagerly putting idled rigs back to work on capped wells should energy prices mount a sustained recovery.

No wonder Goldman Sachs commodities analyst Damien Courvalin wrote to clients earlier this week that any OPEC deal won't be enough to stop oil prices from falling. Not only was Saudi production set to decline into the end of the year based on seasonal trends but Goldman's updated supply-demand forecast pointed to a renewed build of already swollen inventories in the fourth quarter.

As a result, Courvalin is looking for oil prices to fall from $47 now to $43 a barrel by the end of the year (vs. a forecast for $51 a barrel previously). So while an OPEC deal could "support prices in the short term," assuming its finalized in November, he finds "the potential for fewer [production] disruptions and the relatively high speculative net long positioning instead leave risks to our forecast squarely skewed to the downside."