U.S. equities just can't be bothered right now. The Dow Jones Industrial Average remains in a multi-month holding pattern just above the 18,000 level first reached two years ago.

The apparent calm masks a number of game-changing catalysts: Another Federal Reserve interest rate hike, as soon as December, despite tepid economic growth. Rising geopolitical tensions. The prospect of either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump winning the White House. The ongoing corporate earnings recession. China's over-indebtedness. And more.

Why has this all largely been ignored? A big reason: The steady flow of capital into the equity market via corporate buyback and dividend programs. But that too could soon be ending, if it hasn't already.

Related: 7 Big Risks That Could Derail the Stock Market’s Rally

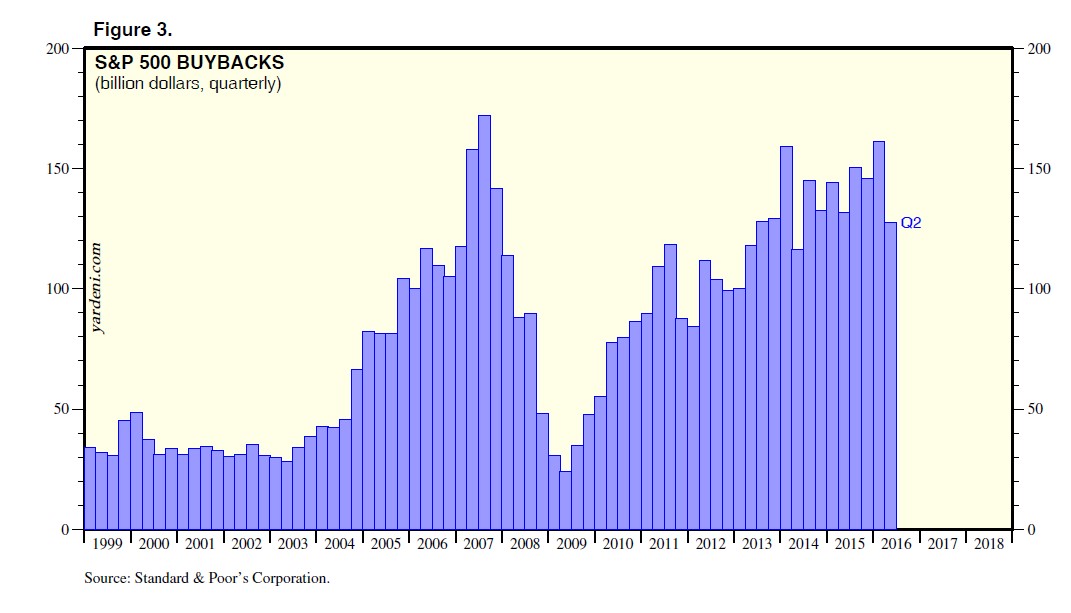

Research from Goldman Sachs shows that 90 percent of S&P 500 companies will report earnings by Nov. 4 — meaning they are in a stock buyback blackout period. According to Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates, the "biggest force in the stock market right now is the buybacks and mergers and acquisitions." Dalio adds that those lines of activity account for "something like 70% of the percent” of the buying action in the stock market. That could be just the thing to push the Dow back under the 18,000 level for the first time since July.

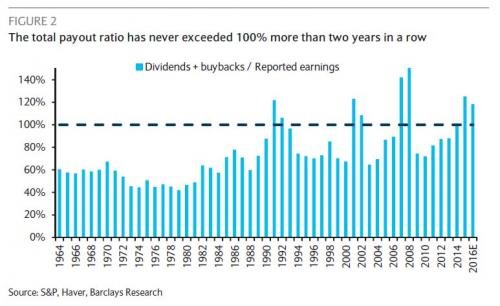

Remember, this earnings season is expected to be the fifth consecutive quarter of falling profitability. As a result, analysts at Barclays Capital are warning that shareholder payouts (dividends and buybacks) are exceeding cash flow at a $115 billion annual rate. Unless profitability and revenue growth return soon, companies will be forced to scale back these capital returns, and thus, remove a major source of buying demand from the stock market.

Related: As the Recovery Falls Short, the Fed Eyes a 'High Pressure' Economy

Historically, payouts haven't exceeded earnings for more than two years in a row as business cycles wind down. It happened in the early 1990s. It happened during the dot-com bubble. It happened before the housing crisis. And it's happening again right now.

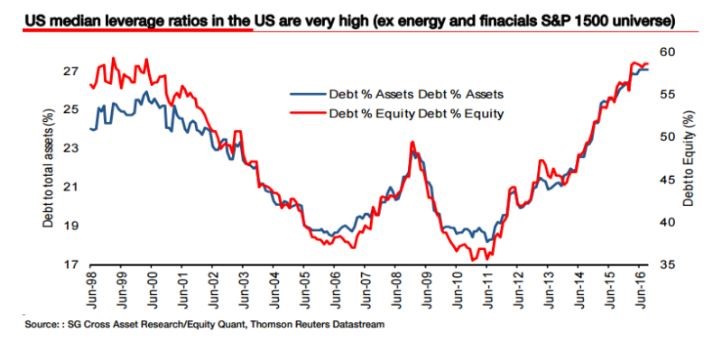

Another wrinkle to the story is how highly leveraged, or indebted, corporate balance sheets are compared to where they were coming out of the financial crisis. This limits the ability of companies to manage downturns in earnings growth, like we're suffering now, since interest payments are larger.

Europeans refer to this dynamic as balance sheet "gearing," in that it makes the rise and fall of net income more and more sensitive to the ups and downs of revenue growth. Like shifting up a gear in your car.

That works great on the upswing of a business cycle, as top-line growth combined with cheap debt financing encourages share repurchases, which lowers the free float share count and really juices earnings per share metrics (and thus, corporate pay); it doesn't work so well when revenue declines, interest payments eat into net income and profit margins drop rapidly.

Related: What’s Ailing the Economy? Political Paralysis May Be the Biggest Problem

This downward spiral is already happening, as two well-known blue-chips demonstrate. Consider that IBM (IBM) sales have been falling for 18 consecutive quarters, or more than four years. Or that Caterpillar (CAT) hasn't posted a single year-over-year increase in global sales in 45 months.

Analysts are hopeful that a turnaround is coming, but with industrial production falling for 13 straight months — the longest non-recessionary decline in U.S. history — it's becoming increasingly hard to justify that expectation.

According to Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research, buybacks were already starting to slow heading into the third quarter. S&P 500 buybacks declined to $128 billion in the second quarter from $161 billion in the first quarter. Overall, buybacks have totaled $3.1 trillion since the start of the bull market in 2009 vs. $1.5 trillion in the previous cycle — something Yardeni has labeled the "slow-motion LBO" (or leveraged buyout) of the stock market.

Now with earnings and cash flow drying up and debt financing becoming pricier (as long-term interest rates drift higher), the slow-motion buyout is about to come to an end.