Happy Monday! "Top Gun: Maverick" has reportedly become the first Tom Cruise movie to top $1 billion in global box office receipts. But we feel the need, the need for fiscal news. (Cut us some slack. It’s Monday.)

Social Security Set for a Huge Cost of Living Increase

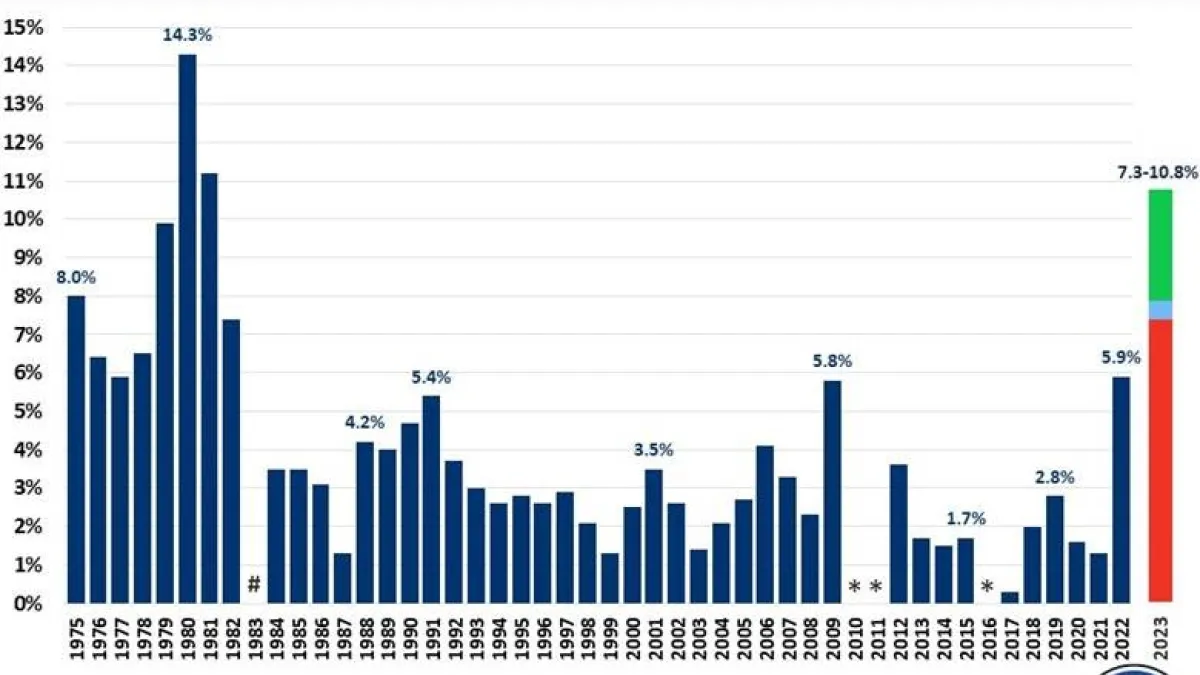

Social Security’s annual cost of living adjustment for 2023 will be the highest in four decades, according to projections from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

While benefits this year were boosted by 5.9%, the adjustment for next year is projected to be between 7.3% and 10.8%, depending on the path of inflation. The final number is likely to be somewhere in the middle, and could be one of the highest increases ever (see chart above). Social Security bases its cost of living adjustments on changes in the Consumer Price Index, a measure of inflation calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget adds that the large cost of living increase could speed Social Security’s insolvency, making it occur a year or two earlier than the currently projected year of 2035.

How Interest Rate Hikes Are Raising the Cost of the National Debt

As the Federal Reserve pushes interest rates higher in its campaign against inflation, the cost of servicing the country’s debt is rising, too. Working with analysts from both the Treasury and the Social Security Administration, The Washington Post’s Allan Sloan has come up with an estimate of just how much higher rates are costing the U.S.: about $128 billion a year.

Looking at the portion of the national debt owned by the public — $23.88 trillion as of the end of March — Sloan determined that 29% of the total will need to be refinanced between March 2022 and March 2023, or roughly $6.9 trillion. Interest rates are now more than 1.75 percentage points higher than they were at the end of 2021 due to the Fed’s rate hikes, and at the new higher rates the U.S. will spend an additional $121 billion per year in interest on that refinancing.

The rest of the national debt — $6.52 trillion — is intragovernmental, owned mostly by federal trust funds. While accounting for that debt is a bit trickier, Sloan comes up with an estimate of $7 billion in additional costs each year due to higher interest rates as debt gets refinanced, bringing the annual total to $128 billion.

“That may not sound like much, given the trillions of dollars of investment wealth that have been vaporized by the Fed’s higher rates,” Sloan writes. “But $128 billion is in the vicinity of the $133 billion total that the Biden budget is seeking for the Energy, Homeland Security and Agriculture Departments. Or is just $2 billion below the total that the Biden budget proposes to spend for the Interior Department, the Labor Department, the Commerce Department, the Treasury, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the National Science Foundation, the Social Security Administration and the Corps of Engineers. Combined.”

Democrats’ Last Chance to Save Their Economic Agenda

Congress is out this week and next for the July 4 holiday — technically, the House has a two-week stretch of district and committee work while the Senate has a “state work period.” When lawmakers return, Democrats will be racing to finalize a scaled-back economic spending package that salvages portions of the $2 trillion budget reconciliation plan that failed in December.

The Washington Post’s Tony Romm provides an overview of where the new package stands — and yet another reminder that the fate of the effort largely rests with Sen. Joe Manchin, the centrist West Virginia Democrat who scuttled the previous version of the legislation and has been negotiating a new agreement with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY). Democrats, Romm says, “have about three months to broker the sort of compromise that has eluded them for more than a year; otherwise, they may lose the ability to adopt the bill under a special legislative tactic that allows them to bypass a GOP filibuster in the Senate.”

What might be in the package: The new bill will be far narrower than the Build Back Better plan passed by House Democrats last year. It’s likely to center around measures to lower prescription drug prices and combat climate change while also including other “energy security” programs sought by Manchin. It’s also likely to include some tax increases that will be used to pay for the new programs and reduce the deficit.

What might not make it: As Democrats have sought to appease Manchin and resolve internal divisions, a slew of proposals that might have provided some relief from rising prices have already fallen by the wayside. Democrats’ expanded Child Tax Credit, which expired at the end of last year, appears unlikely to be renewed, and the party’s earlier plan to improve housing affordability has also been dropped from discussions. The final bill, Romm notes, will also leave out other Democratic plans that had been considered earlier — “no free prekindergarten, no rebates for child care, no aid for elder care, no paid family and medical leave.” Now, Romm reports, “a broadly supported attempt to lower the price of health insurance by extending subsidies under the Affordable Care Act remains at risk of falling out of the package entirely.” Manchin’s cost concerns reportedly remain an obstacle to keeping those enhanced subsidies, meaning that some 13 million people could face significant premium increases for 2023.

A factor for the Fed: Economist Jason Furman, who led the Council of Economic Advisers under President Obama, tells Romm that whatever Democrats do or don’t do with this bill will affect the Federal Reserve as it looks to rein in inflation. “Anything that Congress does that adds to inflation will lead to more interest rate increases,” Furman said. “Anything Congress does to take the pressure off inflation will consequently lead the Fed not to raise interest rates as much. This is much more of an interaction between fiscal and monetary policy than one would have expected a year ago.”

The bottom line: Discussions over the coming weeks may determine whether Democrats can resurrect elements of their economic agenda as they try to demonstrate to voters that they can deliver on some of their promises.

Quote of the Day

“I don’t see what permanent structures that the Democrats created in their first two years. Obamacare was a permanent structure.”

Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform, a conservative advocacy group, as quoted by The Washington Post’s Michael Scherer in an article looking at how those on the political right have posted a string of victories even as Democrats control the House, Senate and White House. Jim Kessler, a Democratic strategist at Third Way, a center-left think tank, told Scherer: “Republicans have had a 50-year plan to win the long game and Democrats have mostly worked to win the next cycle.”

Congress Extends Summer School Lunch Program

Late Friday, the House approved a $3 billion piece of legislation extending a pandemic-era school meal program that provides lunches during the summer to students regardless of income. The bill cleared the Senate on Thursday, with approval coming shortly before the program was scheduled to expire on June 30.

The Keep Kids Fed Act will also boost the per meal reimbursement rate next year — above pre-pandemic rates, but below the temporary levels approved during the pandemic — and provide more leeway for schools to satisfy nutritional requirements as they struggle with supply shortages and inflation.

At the request of Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), the bill revives a pre-pandemic requirement that students from families with incomes above the poverty line pay for their meals at a reduced rate. Advocates had pushed for a continued suspension of that requirement, but Republicans in the Senate objected.

Under pandemic-era waivers, about 30 million children received free school lunches in the most recent school year, the New York Times’ Stephanie Lai and Linda Qiu report. Before the pandemic, about 20 million students received free school lunches, and about 2 million purchased lunches at a reduced price.

White House Sitting on Billions in International Food Aid: Report

Congress approved more than $5 billion in global food aid as part of a $40 billion package responding to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but the Biden administration has yet to spend the money, to the frustration of some lawmakers, Politico’s Meredith Lee reports.

About $4.3 billion is intended specifically for disaster relief, but the United States Agency for International Development has yet to disburse any of the cash, despite a growing food crisis in parts of Africa and the Middle East driven by surging grain prices in the wake of the Russian attack.

Sarah Charles, a top official at USAID, said last week that the organization wants to disburse a bit less than half of the money before September, with the rest being held until the beginning of the next fiscal year in October.

Meanwhile, the World Food Program — which is part of the United Nations and is now run by a former Republican governor of South Carolina — expected to receive more than half of the disaster relief funds immediately from USAID and disburse it before October. But USAID has yet to transfer any of the money — and the delay is becoming a political issue, with some lawmakers questioning the need to provide so much aid in the first place.

“In two years, there may be a different sheriff in town,” a WFP official told Politico, referring to the potential return to power for Republicans in Washington. “If too much is still sitting there, we’re going to look like we cried wolf.”

News

- Democrats Race to Revive Economic Package as Inflation Spikes – Washington Post

- Experts Question Effectiveness of Gas Tax Break – The Hill

- G-7 Unveils $600B Plan to Combat China’s Global Reach – Politico

- Biden Commits $200 Billion to Global Infrastructure Plan Meant to Counter China – The Hill

- Supreme Court Sides With Doctors Convicted of Overprescribing Opioids – Washington Post

- Will Health Insurers Continue to Cover Abortion Now That Roe Has Been Overturned? – Politico

- Economic Fallout of Dobbs Ruling Will Hurt Poor Women Most – Axios

- Americans’ Views of Economy, Finances Worsen: Poll – The Hill

- This Tax Season, IRS Answered Just 10 Percent of Taxpayer Calls – Washington Post

- Schools Are Spending Billions on High-Tech Defense for Mass Shootings – New York Times

- US to Announce Purchase of Medium- to Long-Range Surface-to-Air Missile Defense System for Ukraine – CNN

- Food Inflation Relief Is Within Sight as Crops and Crude Pull Back – Bloomberg

- American College of Physicians Calls US Food Insecurity a Threat to Public Health – The Hill

- Millions in California to Get up to $1,050 in ‘Inflation Relief’ – Bloomberg

Views and Analysis

- Larry Summers Nailed Inflation. But Is He Right on What Comes Next? – James Mackintosh, Wall Street Journal

- Powell’s Path to 2% Inflation Needs Luck or, Failing That, Pain – Craig Torres and Matthew Boesler, Bloomberg

- Semiconductor Legislation Failures Show Why the U.S. Struggles to Compete – David Ignatius, Washington Post

- America Is Backsliding, and All of Us Will Pay for It – Timothy Noah, The New Republic

- Why This Economy Is So Hard to Figure Out – Nathan Bomey, Axios

- Did Corporate Greed Fuel Inflation? It’s Not Biggest Culprit – Paul Wiseman, The American Prospect

- Drug Pricing Reforms Hinge on the Executive Branch – David Dayen, The American Prospect

- How Will Roe’s Fall Affect Politics? No One Knows – Jonathan Bernstein, Bloomberg

- The Pandemic Is in a Twilight Zone. Enjoy It — but Stay Safe – Washington Post Editorial Board