Incompetence at the Drug Enforcement Agency may be contributing to a shortage of medications such as morphine and the anti-anxiety drug lorazepam. That’s the takeaway from a scathing 80-page report from the Government Accountability Office, which blames the DEA for an increasing shortage of prescription drugs that contain controlled substances.

Related: When Doctors Have to Play God Over Drug Shortages

The DEA is in charge of regulating these drugs because they pose risks for potential addiction and abuse. The agency is required to set quotas that drug manufacturers rely on to know how much they can produce.

The problem is that the DEA isn’t providing manufacturers with the quotas on time — and hasn’t for more than a decade, according to the GAO.

The auditors said that between 2001 and 2014, the DEA failed to report the quotas to manufacturers on time. The drugmakers say that delayed their production process and often resulted in shortages.

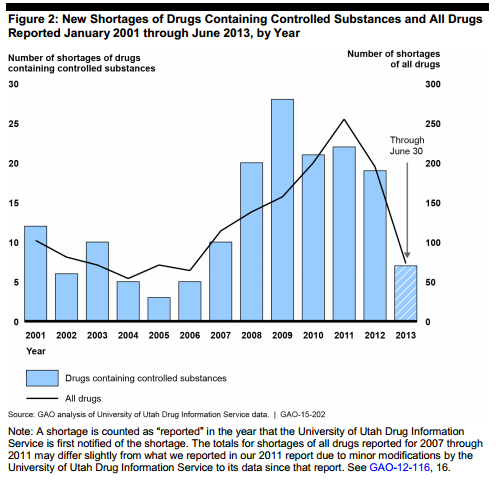

According to the GAO, these drug shortages 2009 but still remain far for frequent than they had been prior to 2008. About 70 percent of the 168 shortages reported between January 2001 and June 2018 occurred after 2007, the report said.

Most of these shortages lasted for more than a year and involved pain reliever drugs produced by just one manufacturer, the report said.

Related: The $1,000 Pill That Could Cripple the VA’s Budget

On top of the delays, DEA’s quotas were riddled with errors. The auditors estimated that at least 44 percent of quota records in 2011 had mistakes, though that figure went down to 10 percent in 2012 when quotas were first reported electronically. Even so, the problems were still serious enough to slow down the production process.

What’s worse, the GAO said the DEA had no way to know if its own records were accurate. The agency “does not have reasonable assurance that the quotas it sets are in accordance with its requirements,” the report said.

The DEA blamed the problems on inadequate staffing and resources.

Related: Get Ready for a Surge in Costly Specialty Drugs

Auditors also blamed a lack of coordination between the DEA and the Federal Drug Administration, which is responsible for keeping record of all drug shortages.

The auditors said the agencies are supposed to work together to combat shortages of drugs containing controlled substances. If the FDA determines there’s a shortage of a life-supporting or life-sustaining drug with a controlled substance, it can request that the DEA increase the quota.

Auditors found that they two agencies haven’t even established a “sufficiently collaborative relationship.” Far from it. They can’t even agree on the definition of a drug shortage.

In one example, officials at the DEA criticized the FDA for not investigating or validating information about drug shortages that it posts on its website — adding that the FDA “encourages manufacturers to falsely report shortages to obtain additional quota.” The FDA, for its part, disputed that claim and said it takes steps to investigate each shortage it posts on its website.

Related: We Can Find Consensus on Health Care Cost Reforms

“Given such barriers to coordination, DEA and FDA cannot effectively act to prevent or alleviate shortages,” the auditors concluded. They added that although the agencies have a “memorandum of understanding” it hasn’t been updated since the 1970s.

The GAO recommended that the agencies quickly update that memorandum. The Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees both agencies involved, agreed.

Separately, the GAO recommended that the DEA develop a policy to better evaluate its quota process in order to prevent so many errors. The DEA, though, disagreed with the GAO’s assertion that there is any relationship between DEA processing errors and drug shortages.

The agency went on to criticize the GAO for not understanding how quotas are evaluated and said it was unfair to blame the agency for the manufacturer’s production failures.

Top Reads From the Fiscal Times: