Outrage over how Congress spends taxpayer money is never in short supply in Washington. Even most members of Congress will tell you that they are steamedc at how Congress spends taxpayer money. But among the policy analysts who follow budget and appropriations battles, what produces even more bitterness and rage is the way that Congress gets away with talking about how it spends money.

Most voters’ attention spans, when it comes to matters of taxation and spending, are measurable in seconds at best. Members of Congress know this and have become adept at crafting explanations for government spending that creates a veneer of plausibility over what most serious students of accounting would charitably call gimmicks, and what in other contexts might be called fraud.

Related: States Keep Using ‘Gimmicks’ to Balance Their Budgets

The Committee for a Responsible Budget is one of those watchdogs that lives down in the weeds of U.S. fiscal policy, and it has developed a handy chartbook illustrating some of the more egregious tricks lawmakers use to make it look as though they are being more responsible with tax dollars than they really are.

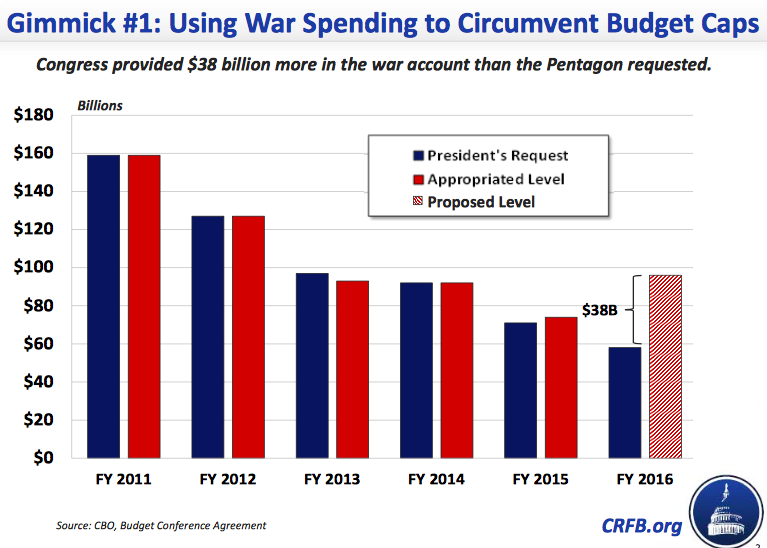

For example, Congress has for years used funding for the U.S. military’s activities in Iraq and Afghanistan to fatten the Pentagon’s budget beyond what the Department of Defense and the White House have said was necessary. The Conference Budget Agreement for Fiscal 2016 is one of the most egregious examples, adding $38 billion in unrequested funding under the guise of providing for the troops.

The extra money is placed in the Overseas Contingency Operations fund, which Congress conveniently made exempt from budget scoring. It amounts to a $38 billion violation of the statutory cap on defense spending in the next fiscal year.

Related: Outrageous Public Pensions Could Bankrupt these States

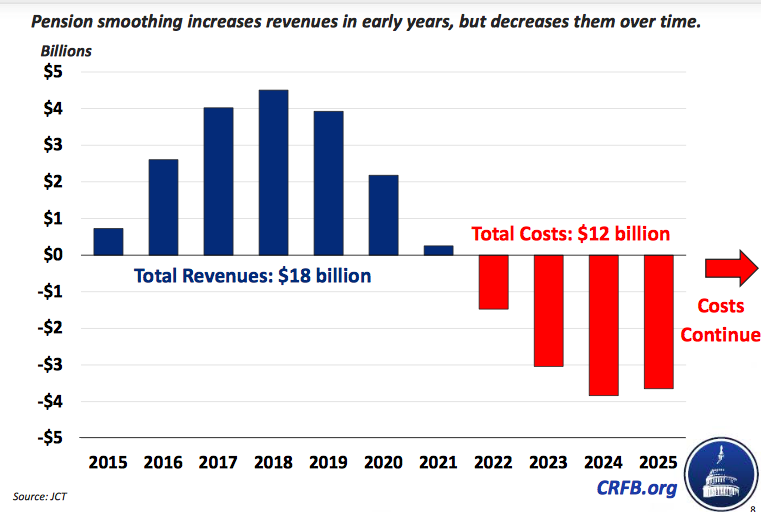

Another favorite technique for disguising runaway spending is “pension smoothing,” a particularly insidious trick because it temporarily generates an increase in federal revenue, but only at the cost of significant future losses.

Pension smoothing allows companies to postpone contributions to their employee pension funds, which means they lose an immediate tax deduction, which increases federal tax revenue in the near term. However, the companies will eventually have to make those pension fund contributions – with interest – and will get a tax break on them when they do.

It’s the sort of thing that drives policy experts nuts. Tax Policy Center director Len Burman, considering a proposal to rescue the federal Highway Trust Fund with the “revenue” from pension smoothing, addressed the issue last year.

“This means that [companies’] tax deductions for pension contributions are lower now, but the actual pension obligations don’t change, so contributions later will have to be higher—by the same amount plus interest. In present value terms (that is, accounting for interest costs), this raises exactly zero revenue over the long run. Let me say that again using all capital letters to express my frustration. THIS $6.4 BILLION REVENUE PROVISION RAISES NO REVENUE OVER THE LONG RUN!!!”

Related: Why States Are Rushing to Give Tax Breaks to Military Retirees

Did I mention it drives them nuts? Because it really does.

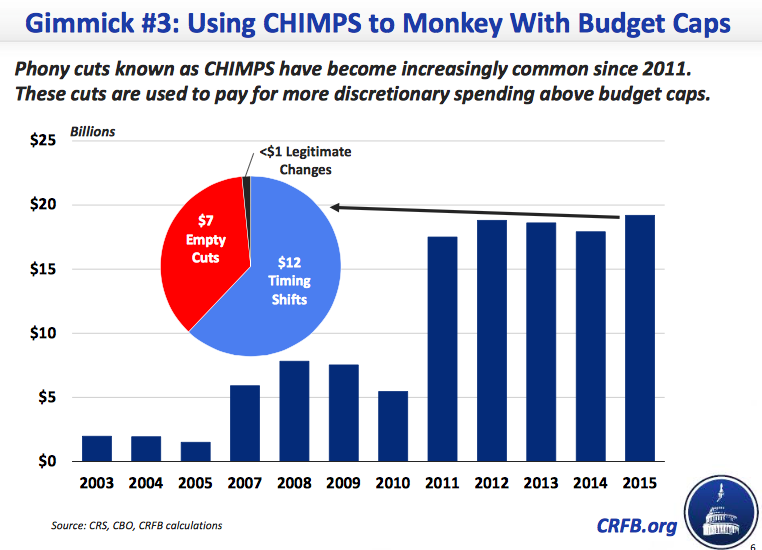

Another method of disguising budget shortfalls is what CRFB refers to as “CHIMPs,” short for Changes in Mandatory Programs. Typically, these involve budget rules that block statutorily required spending for a limited amount of time but allow for the full budgeted amount of funding to be disbursed eventually.

Under Congressional math, these “cuts” simply postpone spending into the future while recognizing the postponement as an actual spending cut for the purposes of the federal budget.

According to the CRFB, “CHIMPs allow policymakers to offset discretionary spending over current limits with mandatory spending cuts. While the principle is sensible, in reality most of the mandatory cuts either reduce spending that would have never occurred or count one-year spending delays as if they are spending cuts.”

The list goes on, and the CRFB documents it in depressing detail here.

Top Reads from The Fiscal Times